by Dahlia Watson

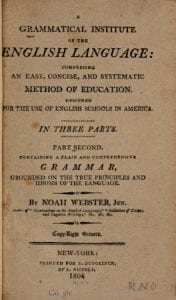

Last semester in my English course on New Romanticism, we had an assignment similar to this one in which we searched through archived lyrical Ballads from the Romanticism period. Both times I thoroughly enjoyed accessing historical literary information that isn’t typically instructed in the classroom. This time around I was more engaged and interested because the artifacts provided insight on my country’s history. I was most intrigued by Noah Webster’s “The Grammatical Institute of the English Language” published in 1804. This 136 page descriptive linguistic outline functions to “furnish schools with a collection of rules or general principles of English grammar” (Webster 3). As a linguistics student, I have always desired to understand the significance of prescribed grammar and the stigma against descriptive grammar. In the History of English course offered at the College, I learned that during the second half of the eighteenth century, a movement formed intending to ‘freeze’ the English language in an attempt to avoid the degeneration of the language. English writer Samuel Johnson’s dictionary played a significant role in outlining standards for semantic connotations in English. Noah Webster followed Johnson’s lead but his publication was significant in distinguishing a unique American standard of English. The preface of his grammar book includes personal anecdotes about his decisions to include idiomatic expressions which have been criticized by linguists but he believes they demonstrate the adaptability of the English language. The preface further details his credibility by attesting to his long hours of studious attention to patterns and phrases commonly used in America. The beginning of the book is really interesting because it reads just like an introductory linguistics textbook, explaining the significance of grammar and differentiating between written and spoken speech. He continues these thorough explanations by describing, with correlating examples, all the parts of speech and their functions. I couldn’t help but to notice how the examples he uses such as “doth” and “mayest” have not been preserved within the language. While some of Webster’s “correct grammatical constructions” would cause confused and concerned glances if uttered in conversation today, other assertions are still stressed in grammar classes today but still are commonly used incorrectly in speech. The distinction between “who” and “whom” is observed on page 41 and still continues to baffle native English speakers today.

Also, the use of the subjunctive was extremely challenging to me when I began learning my second language because I realized that I commonly use the subjunctive incorrectly in English. Instead of correctly conjugating the verb to be as “If I were you,” I frequently say “If I was you,” and I don’t remember a single time when it caused a miscommunication. While some of these grammatical elements are omitted in today’s speech, other definitions such as those for nouns, adjectives and verbs almost identically align with modern grammar textbooks today.

Examining the first ever American grammar guide further confirmed my knowledge of the inevitably of language change. Webster’s ability to outline all the rules, with provided examples and specific exceptional cases requires a lot of thorough study and significant technical writing skills. It’s to say, Webster constructed a document which has had a significant impact on the development and social understanding of American English. Although Webster intended for his “Grammatical Institute of the English Language” to establish a set standard for how English should be taught and spoken in America, he forgot one thing in his acknowledgement between the difference between written and spoken speech; spoken speech is forever evolving and cannot be regulated by prescribed grammatical rules.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433069256646&view=1up&seq=28&skin=2021