Channeling Anarchy after Whitman

Specimen 4: Wishing America never happened

I. Anarchy is a stone untapped

“First what do we understand under ‘Anarchism’? Anarchism practical, metaphysical, theoretical, mystical, abstractical, individual, social?” Vladimir Nabakov, Pnin

“If you meet the Buddha, kill him”- Linji

I must admit once more: Whitman was never an Anarchist. Failing the Native American, I’m cutting him out. Refusing to renounce his class, or use it to shed light on oppression, leaves Whitman looking more like a fascist. My old approach of heralding W’s anarchic tendencies was far too lenient; I have had to let him go. But when I increase the breadth of context in which we place my reading of Whitman, it has enabled a different reading. What I see is a white male of class privilege, the product of a long developing dominant culture–a culture birthed as early as the Great Roman Empire, and exponentiated by the Industrial Revolution. Finally, when I zoom this far back, I see the threads to which Whitman was tied. Class is the hardest thing to break. If W were to be an anarchist, he would do this with zeal.

Crimethought belongs to no one. Crimethinc. is you, whenever you question authority or hierarchies dictating to you your role in society or community. Crimethought has happened in pockets of Western history since the dawn agriculture, from peasant uprisings to Temporary Autonomous Zones (Hakim Bey) like proto-anarchist Pirate Utopias*

*I say ‘proto-anarchist’ with the sense of Anarchism being a philosophy only formally developed (by old white men) in the Enlightenment Era. For more on Temporary Autonomous Zones, see Hakim Bey’s book of that tile.

I will once again require a revamp my linguistic interpretation of Anarchy: Anarchy as an enlightened state.* Anarchy–the dissolving of hierarchies, the dissolving of the self to an ecological social organization, the elimination of oppression–makes relentless demands. That is why those, like W, who even hint at it, who take up its spirit, must be critiqued by other proponents of Anarchy. For Anarchy to be true, it’s advocates must hold up to such criticism. Anarchy, then, has similarities to both the process of Glorification in Orthodox Christianity and the attainment of Nirvana in the Zen tradition. Even the bearded monks on Mt. Athos, fingering their rosaries, ask for perpetual forgiveness. The initiation process for a Zen monk involves repeatedly answering the riddle of a zen koan. But where Anarchy is different is that is not holy and untouchable like God, but hard, ecologically innocent as a stone**. This is where Whitman falls.

Stone

Go inside a stone

That would be my way.

Let somebody else become a dove

Or gnash with a tiger’s tooth.

I am happy to be a stone.

From the outside the stone is a riddle:

No one knows how to answer it.

Yet within, it must be cool and quiet

Even though a cow steps on it full weight,

Even though a child throws it in a river;

The stone sinks, slow, unperturbed

To the river bottom

Where the fishes come to knock on it

And listen.

I have seen sparks fly out

When two stones are rubbed,

So perhaps it is not dark inside after all;

Perhaps there is a moon shining

From somewhere, as though behind a hill—

Just enough light to make out

The strange writings, the star-charts

On the inner walls.

~ Charles Simic ~

*From ideal to practice: Is this ideal only unattainable as an individual? Could this ideal be attained by an “intentional commune” (Communes in the Counter Culture, Keith Melville)? Surely, for the ideal to come into practice requires Maximalism: all tactics are neccesary. The full spectrum is required: from Individualist-Lifestyle Anarchy rooted in Situationalism, to pockets of counter-cultural communities, to large scale insurrection. Therefore, Whitman was not an Anarchist because he did not engage in a radical community. Whitman never renounced his male class privilege to aid a revolution. (The root of the word is “revolve”, meaning to turn back). He did, however, share a lot in common with the lineage of Libertarian male dissenters from Thoreau to Alan Ginsberg, who practiced what Raoul Vaneigem called the “Revolution of Everyday Life” (in his book so-called). This has to be a first step to Anarchy in practice.

**Social ecologist, Murray Bookchin, and Anarcho Primitive, John Zerzan, both adamantly argue that Anarchy is an organization of people rooted in the principles of ecology. Additionally, they argue this is the most humane type of organization. “Morals”, they say, and crime are dichotomies that arise out of hierarchy, and are not intrinsically part of human nature. Cooperation is far more natural (and neccesary in survival) than competition within a species. Mutual-ism and diversity are more important than species domination in a forest eco-system. Anarchy is rooted to the earth rather than to a higher plane. (See, Post-Scarcity Anarchism and The Pathology of Civilization).

II. Co-opting Resistance

The dominant culture will always attempt to consume forms of resistance. Sometimes, as in a panopticon, the prisoners (us) police themselves. America is called ‘The Melting Pot’ because it boils every aspect of diversity down to a bland grey soup. Since Free Trade opened its flood-gates, the pot is no longer even an American phenomenon. For linguistic reasons, I never say I am American. The word has become a fetish of unsustainable economic growth and consumption that is worshiped far outside the confines of the Nation. This “Americanism”, this melting pot, has become a black hole that is selling “American Culture” while devouring small, poor cultures. The State, from its inception, has overtly snuffed dissident political opinions or ways of organizing ourselves as communities. Sacco & Vanzetti were murdered. Once, in the West, it was our divine precedent to conquer the “savage” nations; now manifest destiny is off somewhere, writing its name in blood oil. But our own media-culture creates ugly shades of grey, co-opting ‘resistance’ and selling it back to rebellious teens for profit. My friend, Mike, was joking: “Remember those kids in high school wearing Fight Club T’s? They didn’t get it.” So that’s why I believe W.B. Yeats got the first part right:

“The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world”*

*I am reading this as a metaphor for an apocalypse that has been happening since the Industrial Revolution, an apocalypse Yeats saw culminating in the fascism of WWI. Note: Yeats uses the term ‘mere’ as total. Also, note his use of the word “anarchy” as derogatory. Much like the way most Western civilized people use the term, he seems frightened and naive about a revolution that would destroy power hierarchies. He lacks what anarcho-primitivists may call faith in the Anarchic principle–the organization of society based on ecology, which seems chaotic when it’s merely complex.

What he failed to see through his occult lens was that forms of resistance aren’t always quelled in overt show of State force. Yes, the State holds a monopoly on violence but there are more subtle ways that it can influence the dominant culture into ignorance or passivity. I liken it to crowd-sourcing–smart businesses now tap the consumers themselves, who rave about a product or help them shape their new ad campaign without asking for a cent. Therefore, contemporary anarchist currents are urgently interested in the ways certain forms of resistance have become part of the world we are trying to change. The 21st Century has brought staggering changes and daunting trends:

Once, the basic building block of patriarchy was the nuclear family, and calling for its abolition was a radical demand. Now families are increasingly fragmented—yet has this fundamentally expanded women’s power or children’s autonomy? Once, one could speak of a social and cultural mainstream, and subculture itself seemed subversive. Now “diversity” is at a premium for our rulers, and subculture is an essential motor of consumer society: the more identities, the more markets. Once, the world was full of dictatorships in which power was clearly wielded from above and could be contested as such. Now these are giving way to democracies that seem to include more people in the political process, thus legitimizing the repressive powers of the state.

In 1981, Simon J. Ortiz sung for what is left of his indigenous culture, and he praised corn as a “seed, food, and symbol of a constantly developing and revolutionary people.” Now corn has been co-opted as the food (ahem, syrup) for a corporate America, a dominant culture that demolished the very natives that taught it grow the crop in the first place. Genetically modified and subsidized, it’s being used in all sorts of Industrial processes, including the food industry, where it is hidden in dozens of grocery foods (Food, Inc.). What fuels this demand for corn is dubious. Factory-farms put cows through a grueling process of genetic transforming in order to eat corn, something they have up until recently never been able to digest. To make way for the vast monoculture was the clearcutting of dozens of forest ecosystems, bringing the number of Old Growth forests demolished in the US up to 98% (Derrick Jensen, Strangely Like War: the Global Assault on Forests)*. My friend was joking about North Dakota, how “All I saw were rows upon rows of corn. There’s nothing there. It’s desolate.” That’s because America has effectually destroyed the beautiful prairie ecosystems that were once as abundant as the Buffalo.

*Which, of course, benefited the logging industry that continually employs the rhetoric that “people need the Timber Industry” and not the other way around. Additionally, this all goes over just fine by the public, which is led by the corporate media to believe that clear-cutting forests is not only vital to their needs, but is beneficial to replenishing the ecosystem. This comes flippantly in the face of ecologists, who have made it obvious that ecosystem degradation and forest fires have consistently worsened due to industrial forestry. Once again, the dominant culture is only fed further by a co-opted Forest Service Agency which supposedly “protects our forests”, and a co-opted corporate media. Am I crazy in that I wish to protect forests?–forests, not tree plantations.

III. Leaving out all the colors (of the black flag)

Whitman, in speaking for everyone, may have been speaking for no one. Or in taking such entitlement to engage in literary civil disobedience, he only inspired others of privilege, joining a lineage of libertarian males embodying anarcho-pacifist ideals without considering the struggles of others towards equality, retribution, Anarchy. I have learned a great deal lately from feminists in our community. They’ve helped me see that even the way we use language can turn easily away from responsibility. Especially as a white male of class privilege, I have to watch the way I write and speak from a sense of entitlement. I have been accused of being condescending to women in the radical community, by co-opting their voices. If you think about resistance in such a way, it is much easier for a radicalized college kid living off a trust fund to engage in riots because he will be able to handle the monetary repercussions of paying bail. Not only are women and minorities statistically less wealthy, they experience severe discrimination in both the judicial process and in the social environment of jail. Whitman, in his poetic project, seems to employ this sense of entitlement as well, verging on co-opting the critical voices of dissent from other communities. Developing what I mention in section II, I believe Whitman is a figure who may not have had the critical consciousness that post-modern radical critics may have, and in so many ways, couldn’t help taking entitlement. Further, I see his most radical elements tamed postmortem, when he is rediscovered by the establishment and the State. When he is taught in the compulsory education system, when highways and shopping malls are named after him, what little radical credibility he has is stripped from him. In essence, we have had to cut him off.

The spirit of Anarchy can quickly turn into a spirit Fascism, depending on who takes it up and how they use language to leave out certain voices. Whitman’s co-opting of marginalized voices will remain problematic in the face of a growing anarcho-critical consciousness. Anarchic thought without responsibility and engagement with marginalized communities, without renouncing privilege, can easily become Fascist. Going far in one extreme makes it easier to flip to the other. This is how I see W’s ideological paradox: W stands for a fresh “American” perspective that arises out of modernism’s desire to “make it new” and Enlightenment ideals of democracy. He calls for an American ethos independent of the burdens of European history, and British imperial oppression. But he does this without taking the philosophy to its responsible ends: withholding any mention or solidarity with Indigenous Americans, on whose blood “America” was built. In speaking for the average (male) American, he was speaking only for the dominant culture of which he was a product. In this sense, no radical community can fully herald him: neither the indigenous resistance movement, nor the purple-black flag of anarcho-feminism, nor the pink-black flag of anarcho-queer, nor the green-black flag of eco-anarchy.

IV. Loving “Nature”, Destroying Eco-systems

The strangest thing about how dominant culture works, is that it admits its best intentions, its “curiousity” of the “other”, while simultaneously oppressing the “other”. Americans have witnessed this in the adoration of the physique of ‘primitives’, the love for the ‘entertaining jolly negro’ and Whitman’s own worship of the ‘mother’. Likewise, “nature” and “wildlife” has been given a simplistic stereotype utilized by the very forces that destroy the real thing: corporate farms use images of homesteads in their branding, car companies depict flourishing meadows in their advertising, appealing to our primal need to relate to nature.*

*Contemporary environmentalists and eco-anarchists agree that the conservation mentality allows the dominant culture to create an ideal of “wildnerness” and “nature” and to conserve tiny fractions of it from any development, while continuing on an extractive, progress-based paradigm everywhere else. (See Tom Wessels, The Myth of Progress and Derrick Jensen’s Endgame). What this has left us with is the sneaky back-room deals of Timber Corporations, illegally felling old-growth forests behind our backs. Essentially we’re left with a surban, developed landscape on the one hand and a threatened “conserved” wildlife on the other. The role of the State in environmental destruction is well documented in Derrick Jensen’s Strangely Like War: the Global Assault on Forests, in which he shows not only a revolving door but a golden arch between seats in federal environmental departments and powerful moguls of the Timber Industry.

Since the Agricultural Revolution** and the subsequent rise of urban centers and civilization as we know it, the human species has been insulating itself from nature. There was a loss of trust in the uncertainties of hunter-gatherer life, and history texts like Genesis reflected this new “domination over nature”. W was as much part of this Industrialized culture as the next man, despite some of his expressions of dissent to social decorum. Despite his love for the prairies, the immense redwood forests, his love for the immense herds of buffalo, I believe his patriotism overrides any real responsibility he feels for its fate. He is just as eager to sing Imperial expansion: railroad development, monuments, and the colonizing of the West.

**I don’t know why it’s called a revolution. ‘Revolution’ includes ‘revolve ‘, meaning ‘to turn back’.

Despite his elegiac tone in his “Song of the Redwood-Tree” and his attributing the trees with “consciousness”, W’s use of language makes him complicit in its destruction. As usual, he entitles himself to speak for the voiceless, putting words to the trees as they say, “Here build your home for good, establish here, these areas entire, lands of the Western shore,/ We pledge, we dedicate to you.” Trees are for homes. Human homes. Elsewhere, he idealizes the logger’s strong masculine traits: “crackling blows of axes sounding musically driven by strong arms,/ driven deep by the sharp tongues of the axes.” The sexualized tone should not be overlooked. The phallic axe penetrates the tree, “deep” with its “sharp tongue”. When he says things like “here heed himself, unfold himself, (not others’ formulas heed,)” it sounds like the spirit of Anarchy. In reality, it is merely a justification of male American arrogance, a complete disregard for the laws of ecology, and the autonomy of the indigenous that were living in harmony with this ecology before the term “America” ever existed. This reinforces what I mention in section III as W’s ideological paradox. In Specimen Days, I came across a sketch entitled “The Prairies and Great Plains in Poetry”, in which W describes the prairies as, “entirely western, fresh and limitless–altogether our own, without a trace or taste of Europe’s soil.” The prairies were neither “fresh” nor “altogether our own”, though W certainly saw it this way from the window of his “first-class carriage”. The prairies belonged to the Indigenous, who nourished themselves from its wild game. Nor were they “limitless”. America essentially depleted this eco-system and its herds. Whitman’s complicity spits in the face of contemporary Anarchism.

V. Loving “Primitives”, Taking their Lands

Maurice Kenny takes a powerful stab at Whitman in “Whitman’s Indifference to Indians”. He questions which demographic Whitman was actually heralding. How wide was Whitman’s hand really? He concludes, “His hero, was not the Greek classic–the noble individual of high birth–but the cumulative average.” But he also wasn’t giving the poor and disenfranchised a voice, and as Pollack argues, he reduces women to mothering roles (Pollack, “In Loftiest Spheres: Whitman’s Visionary Feminism”). He sang of the factory hand, the mechanic, the farmer the bus driver but not the indigenous warrior, shaman, basket-weaver, musician. In essence, Whitman sings the most about male figures doing the brunt-work building empire, either manual labor or slave labor or soldiers. His embrace of all these may win the hearts of American nationalists but never that of Native Americans. Kenny plays devil’s advocate of these soldiers of manifest destiny, “A job was a job–and killing Indians was a job, and jobs could not be found in the large eastern cities.” Boiling things down to jobs is a complacent way to give justification to the State. How often do we hear to this day, politicians harping on “creating jobs”, and apologists of environmentally destructive Industry, “we create jobs you need”?

Whitman loved the “primitives”, “the most wonderful proofs of what Nature can produce, (the survival of the fittest, no doubt–all the frailer examples dropt, sorted out by death).” Or were they sorted out by genocide? Or did W take into account how demanding was the journey they made from the West all the way to the Capital? Perhaps not in his “first class coach”. This exerpt from “An Indian Bureau Reminiscence”, succinctly sums up my thesis: the dominant culture will show affection for a stereotype of that which they oppress, whether its the “primitives” or “Nature”. There is in W, even a hope that they can still be civilized. Because, “for all his paint, Hole-in-the-Day is a handsome Indian, mild and calm. So W either heralds their “gnarl’d” untamed virility, or displays how submissive they are. W did not realize these were respected members of a tribe desperately stooping down to a discourse with the State that was rigged from the start. This distorted admiration was evidenced even in Custer’s depictions of natives (2).

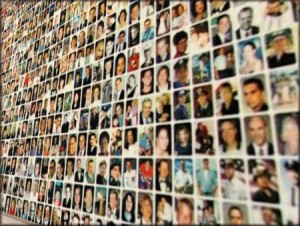

Whitman’s time at the Indian Bureau of the Interior Department is not just dubious, but makes him guilty and actively complicit in the demise of natives, if not outright racist. Kenny also recalls how the Sand Creek Massacre took place the previous year of his employment there. (2). It’s getting old to me the obvious and prevalent corruption in State Bureaus. In a totalitarian move, they dominated all discourse on Native American and colonial relations. This is why the State, any State, must go.*

The biggest tragedy in all this was that Indigenous Americans had a completely different idea of land ownership. Westerners (even Environmentalists) use the phrase, “We took their land”, or “We stole their land”. While I admire this show of solidarity, it overlooks the bigger tragedy of how we exploited the land itself. In other words, “We” developed. the. land. Through extractive Industry, we relentlessly exterminated the Buffalo, and felled the forests like they were an enemy to be driven back all the way to the coastline. Never did Westerners allow themselves to understand the Natives relationship to the land. Those most deserving to “own” the land “owned” it the least.

Whitman may have believed in “Democracy” but what he feared was class equality, what he feared was Anarchy. In “Democratic Vistas” he warns, “I will not gloss over the appalling dangers of universal suffrage in the Unites States.” This fear of actually granting humans their own political autonomy is the same fascist strain in America that led to the Orangeburg massacre at the University of South Carolina in 1968, in which police killed three young men and injured twenty-eight more. Again the killing was inevitable when the State disgraced the black minority by sending down the National Guard in fear of insurrection. Whitman goes as far as to advocate for American Imperialism:

“In those respects the republic must soon (if she does not already) outstrip all examples hitherto afforded, and dominate the world.” In his footnotes, he proceeds to praise how much the Nation had already grown, liking America to Rome, and praising the “river, lake, and coast” as a great place for “commerce”. It turns out, green is the color of money.

VI. Ortiz returns to Sand Creek