Upon cracking open “this connection of everyone with lungs” I had never experienced Juliana Spahr before. Spahr’s poetry began on page 3 and immediately I was intrigued. By page 5 I was wondering where Spahr was going with all of this. The poetry was repetitive and although I appreciated it I found myself getting somewhat bored between the space between the hands and the breathing in and out. I stuck it out and by page 8 I had to stop. I had to stop not because I was bored but because I was so in awe of what I had just read. Long moments of profound thought provoked by incredibly powerful sentences delayed the rest of my reading.

Upon cracking open “this connection of everyone with lungs” I had never experienced Juliana Spahr before. Spahr’s poetry began on page 3 and immediately I was intrigued. By page 5 I was wondering where Spahr was going with all of this. The poetry was repetitive and although I appreciated it I found myself getting somewhat bored between the space between the hands and the breathing in and out. I stuck it out and by page 8 I had to stop. I had to stop not because I was bored but because I was so in awe of what I had just read. Long moments of profound thought provoked by incredibly powerful sentences delayed the rest of my reading.

I read the rest of “this connection of everyone with lungs” in one sitting. Multiple times I found myself reduced to tears because of how moving the book is. By the end of the book I had formally decided that this was a book that I was not including in the “book buy back” at the end of the semester, even if they were to offer me $50.00 for its 75 short pages.

Juliana Spahr really speaks to me. The parrots, the lungs, the teetering of hope, DOW rising but mostly falling, the darkness, the light, the space shuttle, the details of closeness and the calmness of distance, the yous and the mes, the skin – it all speaks to me. I’m not even sure how to write about Spahr yet because I am still so lost in incredible thought.

Spahr’s details are what really makes the book both profound and horrifying.

The details, the numbering, is horrifying. The numbers of people killed, arrested, protesting – horrifying.

“Four have died in clashes in the West Bank town of Jenin./ yesterday, three died in an explosion at a Gaza City house./ Since last Monday US troops have surrounded eighty Afghans/ and killed eighteen.”

The numbering goes on. And Spahr mourns the “huge sadness” that “overtakes us daily because of our inability to/ control what goes on in the world in our name” (Spahr 71). “In our name” – that really gets me, every time I read it. You and me, our name.

The naming – the naming of things is much like Whitman’s catalogues, although for Spahr they serve a different purpose and that purpose is relentless.

“And because the planes flew overhead when we spoke of the cries/ of birds our every word was an awkward squawk that meant also/ AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, UH-60 Black Hawk troop/ helicopter, M2A3 Bradley fighting vehicle, M1A1 Abrams main/ battle tank, F/A-16 Hornet fighter/bomber, AV-8B Harrier fighter/ jet, AH-1W Super Cobra attack helicopter and that soon would/ mean other things also…”

It is this naming of things, of machinery, of artillery that make the poem horrifying. It is Spahr’s blatant act of cataloguing machines we invented for the purpose of killing that makes the poem horrifying. It is the act of naming these things that makes them real, that makes them so real and so deadly. It is this, which makes us think of what we are.

And what are we? Spahr tells us that “Embedded deep in our cells is ourselves and everyone else” (Spahr 31). We are connected with everyone, although Spahr admits she had to think of what she was connected with – a moment of crisis after September 11, 2001. Spahr also had to think of what she was complicit with. “Complicit”, what an interesting word to choose. In her note Spahr writes that –

“I felt I had to think about what I was connected with, and what I was complicit with, as I lived off the fat of the military-industrial complex on a small island.”

A few pages later I find a ripped sheet of lined paper scribbled on by a person who I imagine is the previous owner of this book. The paper reads

“Complicit –

Choosing to be involved in an illegal or questionable act, especially with others.”

This piece of scratch paper combined with Spahr’s ever powerful words made me stop yet again and think. My name is on this world as is yours, and what are we complicit with? What are we in on? And what has it done to others?

Spahr’s poems remind us that we are all in on it. We are all connected. Even in sleep, we are all connected.

“We live in our own time zone and there are only a small million of/ us in this time zone and the world as a result has a tendency to/ begin and end without us.”

Spahr explains what others have failed to explain. In a chilling moment of revelation we learn that

“While we turned sleeping uneasily a warehouse of food aid was/ destroyed, stocks on upbeat sales soared, Australia threatened first/ strikes, there was heavy gunfire in the city of Man, the Belarus/ ambassador to Japan went missing, a cruise ship caught fire, on yet/ another cruise ship many got sick, and the pope made a statement/ against xenophobia.”

Thus our world went on without us and even without our active involvement we have become involved in both the glories and atrocities. Perhaps we have even become complicit with them.

Even in “distance” we are all connected. Spahr tries to comfort herself “with images of exile on this small piece of/ land in the middle of the large Pacific” (Spahr 63) but recalls “That view from space, this view not that seems so without promise, so empty of hope” (Spahr 63). She knows “there is no alone anymore” (Spahr 63).

Even the parrots are here, connected to us in “this habitat far away from/ their origin because someone set them free, someone set them free” (Spahr 18).

Even the parrots are here, connected to us in “this habitat far away from/ their origin because someone set them free, someone set them free” (Spahr 18).

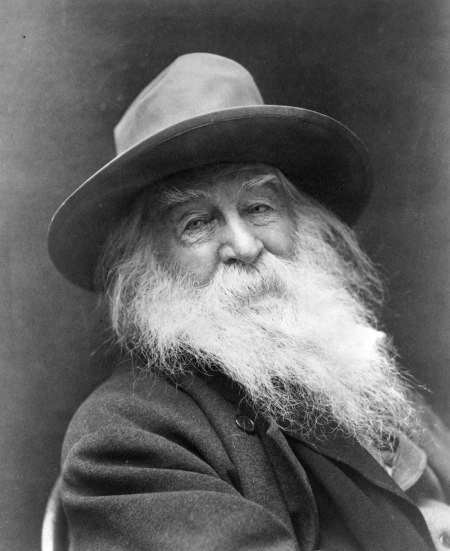

Walt Whitman wanted his “Leaves of Grass” to stop the war, to change the world. I can say that following in his footsteps Juliana Spahr has changed my world and has the potential to change our world, the world we are all connected to.