As you’ve all worked so diligently on your research papers, I thought it would be fitting to post part of a piece I’ve been working on over the course of the semester–a piece I recently published in a journal called Agni. You can read the essay in its entirety here. What follows is a section of the essay in which I discuss C.K. Williams’s recent book On Whitman (2010).

In On Wh

In On Wh![]() itman and Wait, we witness two competing intelligences: a prose intelligence that works through recollection and remembrance, recreating the formative Whitman of Williams’s early career; and a poetic intelligence that more quietly forges an authentic late-Whitmanian presence for Williams’s compositional present.

itman and Wait, we witness two competing intelligences: a prose intelligence that works through recollection and remembrance, recreating the formative Whitman of Williams’s early career; and a poetic intelligence that more quietly forges an authentic late-Whitmanian presence for Williams’s compositional present.

Williams parcels out On Whitman into over two dozen small chapters, most with succinct chapter titles coded to Whitmanian keywords: there’s a chapter on “I” and “You”; chapters on “America,” “Imagination,” “Vision,” “Sex,” and “Nature”; we have “The Voice” and “The Body.” If these signposts bear a recognizable significance for most readers of Whitman, the chapters themselves often surprise with genuinely fresh insights. In the chapter with the shortest title, for example—“I”—Williams explores a deep affinity between Whitman and the seventh-century Greek poet Archilochos, bringing us to the very roots of lyric. In “Sex,” he offers a familiar glimpse of Whitman presiding over the ’60s, but manages to express the exuberance of the moment without overly glamorizing it: “sadly,” he writes of the often illusory freedom that saturated the times, “it didn’t, couldn’t, fundamentally change our anxieties, our propensity for aggression, our basic instinctual conflicts.” And yet there is something to be said, Williams tells us, for the way Whitman casts off centuries-old repressions, the way he eroticizes not only sex, but all of creation.

Here and elsewhere, On Whitman exceeds the standard stuff of poet-prose, which can dwell too often in mere enthusiasm for— rather than true amplification of—its subject. No one has written so suggestively, for example, of Whitman’s connection to Charles Baudelaire. Williams scrupulously documents their affinities: born just a few  years apart, they both compiled their most important work in the mid-1850s, with Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal coming out two years after the first edition of Leaves. Both of their books prompted accusations of indecency and obscenity. Both men were flâneurs in their own way, city walkers wed to metropolitan centers—Paris and New York—that were in the throes of rapid industrial, architectural, and cultural change. Both were poets of love at last sight, of fleetingness and fading impressions. Both wrote of death and evil, of ruins and prostitutes. Williams enumerates and explores these connections with a critic’s assured knowledge and a poet’s knowing intimacy. Noting how both poets strove “to find new routes through the deterministic logics of mind and self that had come before,” he casts Whitman as the “creator of something entirely new, not only like Baudelaire in its matter, but in its utterance, its very shape: he created a new form to enact and encompass the world as he passionately wished it to be.” The subsequent chapter on Hugo and Longfellow, which might seem a strange aside, only deepens the Whitman-Baudelaire connection by annotating their struggles against poetic counterparts who had more fame, more money, and more cultural cachet.

years apart, they both compiled their most important work in the mid-1850s, with Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal coming out two years after the first edition of Leaves. Both of their books prompted accusations of indecency and obscenity. Both men were flâneurs in their own way, city walkers wed to metropolitan centers—Paris and New York—that were in the throes of rapid industrial, architectural, and cultural change. Both were poets of love at last sight, of fleetingness and fading impressions. Both wrote of death and evil, of ruins and prostitutes. Williams enumerates and explores these connections with a critic’s assured knowledge and a poet’s knowing intimacy. Noting how both poets strove “to find new routes through the deterministic logics of mind and self that had come before,” he casts Whitman as the “creator of something entirely new, not only like Baudelaire in its matter, but in its utterance, its very shape: he created a new form to enact and encompass the world as he passionately wished it to be.” The subsequent chapter on Hugo and Longfellow, which might seem a strange aside, only deepens the Whitman-Baudelaire connection by annotating their struggles against poetic counterparts who had more fame, more money, and more cultural cachet.

Williams is a passionate close-reader of Whitman’s work, drawn foremost to what he calls, in the book’s first chapter, “The Music.” “It’s essential to keep in mind,” Williams writes,

that in poetry the music comes first, before everything else, everything else: until the poem has found its music, it’s merely verbal matter, information. Thought, meaning, vision, the very words, come after the music has been established, and in the most mysterious ways they’re already contained in it.

Williams aptly captures the unpredictable, yet somehow precise, music that Whitman’s lines often produce, and he has a supreme sense of the contrastive surprise that accompanies the accrued music of Whitman’s catalogs. If he is at times overly exuberant, that merely reflects the degree to which On Whitman is a book that looks back, unembarrassed, to the energy of his own early encounters with the poet, and also to the miraculous birth of Whitman’s poetic presence, coming, as he seemed to, out of nowhere and everywhere at once in 1855.

This emphasis on a Whitman in the full flush of health inspires and enables many of Williams’s keenest observations. But it also sponsors the study’s neglect of Whitman in age. It’s not that Williams fails to attend to Whitman in his lateness; he won’t give the old bard a break.

Discussing the endless revisions of Leaves that didn’t cease until the Deathbed edition of 1892, Williams writes that Whitman “continued to put it through his mill long after his poetic powers had deteriorated. This is a sad thing to say about any artist, but a side-by-side reading of the different versions makes it undeniable.” This staid narrative of decline is too common in Whitman criticism. Though Williams dutifully registers his respect for Whitman’s stoicism in the face of his increasingly feeble music, he largely sponsors the received account:

even when some twenty years or so later he realized it had left him, had left him even years before that, he expressed no great grief, though he surely had no inkling during those early blazing years that it ever might wane. But, sadly, at some point, it did go bad for him. He lost the connection to his music, not knowing at first hand that he had. Trying to keep it going, after the 1860s, into the ’70s and ’80s, he kept making new poems, but his locutions become odd and awkward, his rhythms uncertain, his diction sometimes almost primitive.

Whitman, to Williams’s deep dismay, resorted to an “endless tinkering” which inevitably “untuned the original power of his symphony.” Trying to guess at the roots of Whitman’s failure, Williams asserts that “he was having fatal trouble sounding like himself, the poet he had been, whose music was diluted now, and weary, maybe because his body itself had begun to be prematurely sick and weary and old.”

Can’t Whitman be allowed to evolve? Mustn’t he? Isn’t harboring a fatal fear of sounding like oneself the mark of any great poet? Shouldn’t Whitman’s music be allowed to change with the debilities of age? And also with the evolving political and cultural crises of post-war America as Lincoln’s grave sacrifice gave way to the failure of Reconstruction, to the rampant corporate greed of the Gilded Age, to the annihilation of space and the tyranny of time as the railroads carved up the countryside and portioned out the day? Deciphering Whitman’s late work requires that we seek to understand precisely how it tracks the decay of both his body and his dream for America. Yes, his late work can seem odd and uncertain, cragged and conflicted, even as it continues to echo some former glory and accomplishment. This remains the essential, contrastive drama of late Whitman, and it gives rise to a strange, difficult, and discomfiting music with a strong critical undertow for those prepared to hear and explore it.

When Williams turns to Whitman’s prose, he comes much closer to recognizing an ideologically complex Whitman. He quotes at length from Democratic Vistas (1871), where Whitman betrays the shadow side of his exuberant poetic optimism: “Never was there, perhaps, more hollowness at heart than at present,” Whitman writes. “We live in an atmosphere of hypocrisy throughout.” He goes on to lament the “depravity of the business classes,” the “corruption, bribery, falsehood, mal-administrating” that saturate public life. After giving voice to this other side of Whitman, Williams notes in a parenthetical aside how similar this sounds to “what we’ve come to know, politics by party, politics as power.” And then, in a crucial insight, Williams asserts: “He already knew the loss.”

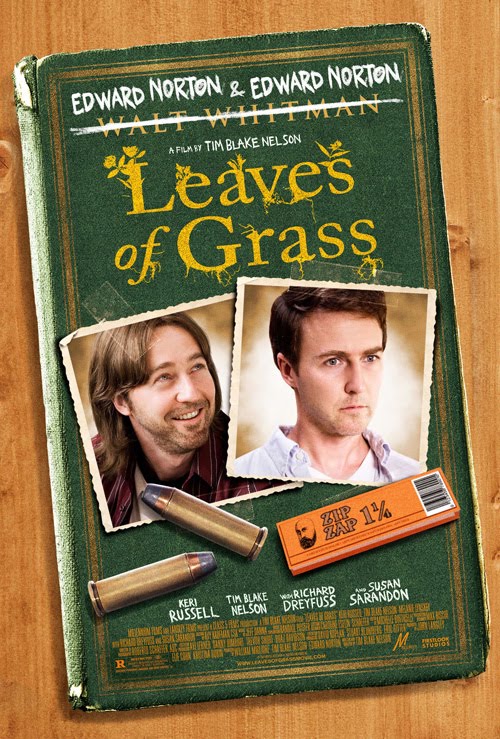

These are the five truest words in On Whitman, perhaps the truest, most necessary words we could say of Whitman today. But Williams abruptly backs away, beating a retreat to the poetry, to the early Leaves of Grass, which he calls “a hymn of praise to the nation, to its people, its land, its nature, its animals.” Over this symphony of optimism orchestrated by (in Williams’s phrase) a “stunningly successful, hardly ever flagging poetical-fictional colossus,” it is difficult indeed to hear the muted strains of Whitman’s lateness.

Williams’s blindness to Whitman’s lateness and all it signifies has its roots not in any disrespect for age or fear of death, but in a profound underestimation of Whitman’s music. Reflecting on Whitman’s teasing question from “Song of Myself”—where he asks the reader: “Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?”—Williams offers this stunning claim:

What’s striking is that there are no ‘depths’ in Whitman, no secrets, no allegories, no symbols in the sense of one thing standing for another, an aspect of matter standing for an element of spirit. Everything in Whitman’s poems is brought to the surface, everything is articulated, made as clear and vivid and in a way as uninterpretable as it can be.

But this seeming tyranny of the ostensible only represents one of Whitman’s many changes of garments. What of the Whitman who writes, in the Preface to Leaves, of the essential poetic qualities of indirection and suggestiveness? The one who writes in “Among the Multitudes” of some far-off reader “picking me out by secret and divine signs . . . / that one knows me,” Whitman declares, before switching to a more direct address: “I meant that you should discover me so by faint indirections.” Whitman, we also recall, was something of an amateur Egyptologist, obsessed with hieroglyphics and their hidden portents. And wasn’t Williams himself utterly convincing when he substituted Whitman for the deeply allegorical Poe, the American poet most often compared to Baudelaire? Whitman felt his late work had plenty of secrets in store.

To be sure, Whitman worried over the status and significance of his late works, asking himself, in the preface to Good-Bye My Fancy, whether he had “not better withhold (in this old age and paralysis of me) such little tags and fringe-dots (maybe specks, stains)?” In a brief note published in Lippincott’s Magazine around the time he released Good-Bye My Fancy, however, Whitman answers his own hesitation in a pointedly distancing third-person voice, declaring that “the book is garrulous, irascible (like old Lear) and has various breaks and even tricks to avoid monotony. It will have to be ciphered and ciphered out long—and is probably in some respects the most curious part of its author’s baffling works.” That ciphering should now begin.

Helen Vendler, who reviewed On Whitman for The New York Times, is less responsive than I am to Williams’s insights, calling the chapter on Baudelaire, for example, more of an interruption than an intensification. She also regrets much of his brash enthusiasm for Whitman as a ’60s icon. While I clearly don’t everywhere agree with Vendler, we share a sense that Williams’s emphasis on a kind of cult of Whitmanian youth distracts from what could be a fuller understanding of Whitman’s lateness. “I do wish,” Vendler concludes, “that he had made more room for the old Whitman, lonely, lingering, as he leaves friends in ‘After the Supper and Talk,’ reluctantly descending the steps, but still talking, ‘garrulous to the very last.’” I agree completely.

Check out Agni to read the rest of the essay, which moves on to discuss Williams’s recent collection Wait.