“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts” (Rachel Carson).

Born in 1819 and dying in 1892, Walt Whitman’s life spanned much of the ever-changing socio-cultural climate of the 19th century. Witnessing the soar of Industrialism in America and, perhaps more impactful, the brutality of the Civil War, Whitman was in the front seat for the overt transformation of his America, the America of his youth, that of the natural world of tranquility and peace and the strength he believed that could be regaled from it. From the onset as a budding poet returning home from a trip to New Orleans, reverberating through the writing of his Annex poetry after publishing his 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass, there is a direct, prevalent and purposeful correlation between Whitman’s life and his poetic work and this evolution of the world around him. As a man, and as a poet, Whitman can be seen to be symbolic of both the Romantic and Transcendentalist poetry of the time, but also evidence of the socio-cultural climate spanning his lifetime. The progression, and often times regression and destruction, of this time period was not only a reflected metaphorically and symbolically as the decaying of Man and Nature in his poems, but also is evidenced by the aging and decaying of the man himself with that, too, reflected by Art.

Born in 1819 and dying in 1892, Walt Whitman’s life spanned much of the ever-changing socio-cultural climate of the 19th century. Witnessing the soar of Industrialism in America and, perhaps more impactful, the brutality of the Civil War, Whitman was in the front seat for the overt transformation of his America, the America of his youth, that of the natural world of tranquility and peace and the strength he believed that could be regaled from it. From the onset as a budding poet returning home from a trip to New Orleans, reverberating through the writing of his Annex poetry after publishing his 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass, there is a direct, prevalent and purposeful correlation between Whitman’s life and his poetic work and this evolution of the world around him. As a man, and as a poet, Whitman can be seen to be symbolic of both the Romantic and Transcendentalist poetry of the time, but also evidence of the socio-cultural climate spanning his lifetime. The progression, and often times regression and destruction, of this time period was not only a reflected metaphorically and symbolically as the decaying of Man and Nature in his poems, but also is evidenced by the aging and decaying of the man himself with that, too, reflected by Art.

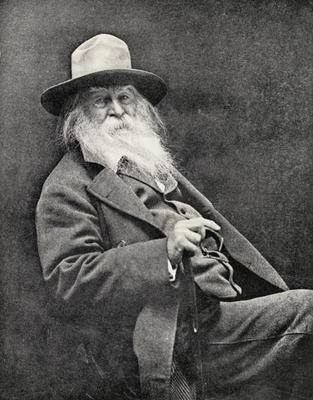

Through the advent of photography during the early 18th century, this newly developed artform helped capture and further illuminate the life both influencing and affecting Whitman’s life and poetry, as well as helped chronicle the life of the poet, himself, from his days as a young idealistic poet until just before his death in the 1890’s, perhaps as a wiser, more enlightened scribe of the history he witnessed unfold. According to Whitman himself, “no man has been photographed more than I have,” and during his life he became “the most photographed writer of the nineteenth century,” with over 130 portraits taken (Folsom). “For Whitman,” again according to Folsom in his article, Photographs and Photographers, “photography was one of the great examples of how nineteenth-century technological advancement provided a concomitant spiritual advancement […] the photograph [froze] time and space by holding a moment and a place permanently in view: it transformed the fleeting into the permanent.”

Photography, then, was a crucial and integral piece of Whitman’s life, capturing a view of, not only the world he felt compelled to eternalize in his writing, but also his journey from a young poet to the old grey beard that was witness to the decay of Nature through Industrialism and Man through War. As the impetus and idea of life and strength being part of and connected to the natural world ends and gives way to the industrialized and decaying America, Whitman’s poetry also shows this decay. As one who can no longer “contemplate the beauty of the earth [and] find reserves of strength” from it, his own reserves fade as he too ages and decays along with these Romantic ideals. Just as the photographs during his life reflected and chronicled both the beauty and the wane, throughout this photo essay, excerpts from Whitman’s poetic works will be visualized and further illuminated by current emblematic photos, chronologically starting with his early years as a Romantic and Nature inspired poet, followed by his poetry reflecting on the savagery of the Civil War and its socio-political ills, and, finally, ending with his reflections on, not only his own life, but of Man, Nature, and the world to come in the twilight of his years. The photographs embodying and echoing the timeless beauty of his words still as dynamic and resounding as when pen was put to paper.

Early Whitman

The world was Whitman’s oyster during his younger days. As Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price note in their biography of Whitman, “no one could have guessed that this middle-aged writer of sensationalistic fiction and sentimental verse would suddenly begin to produce work that would eventually lead many to view him as America’s greatest and most revolutionary poet.” From his childhood in Brooklyn, life in Manhattan, and travels to cities like New Orleans, Whitman had many experiences that influenced his early poetry. However, as Folsom and Price write, Whitman considered himself to be a poet “who speaks from and with the whole body and who writes outside, in Nature, not in the library.” This Romantic and Transcendental connection to his early years as a poet had an indelible mark on the poetry of his first edition of Leaves of Grass and its subsequent versions. Outside of the mind of this up-and-coming poet, America was changing rapidly. Populations were rising and society was evolving as a whole during the 1850’s. There was a creative and industrial boom during this time as well, with the creation of many reputable works such as Moby Dick and “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” all while locomotives continued to mark their paths throughout the country (America’s Best History). And yet, there was still a balance between Man and Nature during this time and this connection breathed heavily into Whitman’s work.

Song of Myself

A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands; How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he. I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green stuff woven. Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord, A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt, Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose? Or I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation”

A poem of 52 sections spanning many lines and pages, “Song of Myself” was published in the 1855 Leaves of Grass. In the expansive poem, Whitman “celebrates himself not simply as the poet Walt Whitman in all of his great complexity, but he transcends his own “me-ness” and in doing so welcomes and embraces all of humanity and the natural world each and every corner of it equally, without reservation” (Drake). In this lyrically written section of “Song of Myself,” Whitman discusses life and Man and its connection to Nature with a child who is holding grass in their hands. This photo replicates the image of the child holding the grass with full hands. This “green stuff woven” within the palms of the child emphasizes this connection between Nature and Man that Whitman discusses with the child. As Whitman says, “I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the vegetation.”

As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life

“I musing late in the autumn day, gazing off southward, Held by this electric self out of the pride of which I utter poems, Was seiz’d by the spirit that trails in the lines underfoot, The rim, the sediment that stands for all the water and all the land of the globe. Fascinated, my eyes reverting from the south, dropt, to follow those slender windrows, Chaff, straw, splinters of wood, weeds, and the sea-gluten, Scum, scales from shining rocks, leaves of salt-lettuce, left by the tide, Miles walking, the sound of breaking waves the other side of me”

“As I Ebb’d with the Ocean of Life” was published as a part of Whitman’s early iterations of Leaves of Grass in 1855. Throughout the poem, Whitman questions his life and identity within society and witnesses the myriad of life as he walks near the sea-side during autumn. This photo was taken in the early morning at a beach in Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina. There is an interconnectedness between all the life in the photo and the excerpt from the poem, from the “splinters of wood, weeds, and the sea-gluten” to the bird looking for food near the water that echo this feeling of fascination which Whitman describes and is inherent thematically in, not only this poem, but this period of his work.

Spontaneous Me

“The same late in autumn, the hues of red, yellow, drab, purple, and light and dark green, The rich coverlet of the grass, animals and birds, the private untrimm’d bank, the primitive apples, the pebble-stones”

“Spontaneous Me” was also published in the 1855 version of Leaves of Grass. A part of his section entitled, “Children of Adam,” “Spontaneous Me” epitomizes the idea of nature being apart of Whitman through a series of images. Moving from the sea to the woods, the colors of autumn were in full bloom throughout James Island County Park. Like the excerpt from Whitman’s poem, “Spontaneous Me,” there is a sublime feeling that can be gathered as Whitman watches the many facets of Nature. Like the life near the ocean, there is this continued representation of the multitudes of life in this excerpt from the many hues of colors blending amongst the woods to the “rich coverlet of the grass” below.

I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing

“I saw in Louisiana a live-oak growing, All alone stood it and the moss hung down from the branches, Without any companion it grew there uttering joyous leaves of dark green, And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think of myself, But I wonder’d how it could utter joyous leaves standing alone there without its friend near, for I knew I could not”

According to Carl Smeller in his commentary on the poem, “I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing,” the poem “was originally published as number 20 in the “Calamus” cluster of the 1860 Leaves of Grass. Smeller goes on to write how this poem “encapsulates this conflict of desires as a tension between homoerotic emotions unrepresentable in poetry and Whitman’s stance of poetic self-sufficiency” while also crafting an image of the beauty in Nature and Man’s connection to it. Although not taken in Louisiana, this photo is of the historic Angel-Oak tree in John’s Island, South Carolina. There is an immensity to standing in front of something as beautiful and grand as the Angel-Oak. Like the excerpt from Whitman’s poem, there are thousands of “leaves of dark green” on the tree. Like Whitman, one cannot help but question the same things he does, how a creature such as this can grow to be so immense, yet generate a feeling of loneliness through its stature. It is both beautiful and haunting at the same time and, perhaps, foreboding to Whitman’s view of life and his body of work.

Whitman and The Civil War

The Civil War not only was a pivotal period of time in the span of American history, but it was also a transformative period for Walt Whitman too. In his book, Walt Whitman, David Reynolds writes that “the war remained a retrospective touchstone for Whitman […] he found that the ideal nation made possible by the war was not mirrored by the reality of postbellum America. Neither the war nor his poetry had purified the political atmosphere […] America’s problems were more dire than ever.” The thousands dead and the intense violence of the war had an indelible mark on Whitman as a man and a as a poet. As Roger Asselineau notes in The Evolution of Walt Whitman: An Expanded Edition, “instead of celebrating the exaltation of the volunteers going into combat, he chanted his infinite pity for the young men whose death made him think of Christ on the cross, or the sufferings of the wounded who had been operated on near the front-lines and of the dying on the battlefields.” He despaired for his country during this troubled time and had to witness the atrocities of the Civil War first hand when he was a nurse to wounded soldiers. The war put a physical and mental toll on Whitman’s body and this began the decay in his perception of what was once an idyllic and Romantic vision of America. This perception was heightened to the extreme with the tragic death of Abraham Lincoln, someone to whom Whitman admired greatly and drew immense inspiration from. These negative impressions of this disjointed and volatile America found themselves imprinted in Whitman’s subsequent volumes of Leaves of Grass and, in particular, his sections called “Drum-Taps”, “Memories of President Lincoln,” and “Autumn Rivulets.”

The Wound-Dresser

“But in silence, in dreams’ projections, While the world of gain and appearance and mirth goes on, So soon what is over forgotten, and waves wash the imprints off the sand”

“The Wound-Dresser” was published in 1865 in Whitman’s “Drum-Taps” cluster of poems during the Civil War. It details Whitman’s intense experiences as a hospital volunteer and nurse during the war and his relationships with many of the wounded soldiers in the hospital. This photo and the excerpt from his poem, “The Wound-Dresser,” emphasize the emotional toll that this war put on Whitman’s psyche. The world will go on after the war, but at what cost to all those that suffered because of it? Time will wash away the pain of the war, but for Whitman, this period of time caused not only great suffering for himself, but also America as a whole was affected deeply.

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d

“I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them, And the white skeletons of young men, I saw them, I saw the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war”

Also published in 1865 and written as an elegy lamenting the death of Abraham Lincoln and so many others during the war, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” shows just how deeply affected Whitman was by not only Lincoln’s death, but the Civil War in general. The poem “intertwines at least two narrative strands— that of the mourning poet who moves from the lilac-covered dooryard into the bird’s swamp, and that of Lincoln’s dead body being carried through the landscapes of post–Civil War America— both of which are frequently displaced by portraits of the land that emphasize nature’s agency” (Gerhardt). What was once a body of work celebrating Man and Nature in Romantic exaltation has now been muddied by the violence and death of the war. This photo was taken at The French Protestant (Huguenot) Church on Church Street in Downtown Charleston, South Carolina. The multiple gravestones lining the churchyard imitate the feeling of seeing the myriads of corpses to which Whitman describes and the haunting aftershocks the Civil War caused.

The City Dead-House

“That house once full of passion and beauty, all else I notice not, Nor stillness so cold, nor running water from the faucet, nor odors morbific impress me, But the house alone – that wondrous house – that delicate fair house – that ruin”

“The City Dead-House” was published in 1867 as a part of Whitman’s “Autumn Rivulets” cluster of poems. A Post-Civil War poem, “The City Dead-House,” isolates the continued despair that Whitman has for his broken America as well as his own aging body at almost fifty years old. The excerpt from the poem emphasizes this despair as Whitman watches what was once a house “full of passion and beauty” turn to ruin. The building in the photo is that of 15 Radcliffe Street in Charleston, South Carolina. Built in 1885, 15 Radcliffe has fallen into disrepair in recent years and what was once a Victorian home with great beauty has now been reduced to a crumbling state. 15 Radcliffe embodies this feeling that Whitman exuded into “The City Dead-House”. His once highly regarded and passionate America has now collapsed under the weight of the Civil War. This dead house in front of Whitman also acts as a mirror to himself, a Romantic and spirited poet now broken-down and despondent while also beginning to feel the effects of old age creeping upon him.

This Compost

“Now I am terrified at the Earth, it is that calm and patient, It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions, It turns harmless and stainless on its axis, with such endless successions of diseas’d corpses”

“This Compost” is the subsequent poem in Whitman’s “Autumn Rivulets” cluster of poems and was published in 1867. With his experiences during the Civil War and the immense pain it caused him psychologically, “This Compost” shows what was once a palpable love for Nature and life become polluted by the aftershocks of the war. According to Jimmie Killingsworth in Walt Whitman and the Earth: A Study in Ecopoetics, the poem “gathers up the threads of the rhetorical and poetic tradition known as ‘the sublime,’ the expression of awe that inheres in ‘human beings’ encounters with a nonhuman world whose power ultimately exceeds theirs,’ inspiring a sense of humility and mortality.” In the excerpt from the poem, Whitman writes “Now I am terrified at the Earth, it is that calm and patient, It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.” The photo, taken at St. Phillip’s Church on Church Street, embodies this idea of Nature growing out of the “corruption” to which Whitman describes, or in this case, the bodies of all those that have died. The flower is placed in the foreground with a serene lighting casted on its petals, but this sublime image of the flower shifts with ever-present rows of gravestones in blurred in the background. Like Whitman’s poem, the connection between the flower and graveyard sends a message of the cycle of death and life to which the earth grows.

The Good Gray Poet

Fifteen years after the end of the Civil War, Whitman was now in his 60’s and entering into the twilight of his life. In 1881-1882, Whitman released a new edition of Leaves of Grass with reworkings of old poems and the addition of new material. Following this release of the new edition of Leaves of Grass, Whitman wrote Specimen Days, an auto-biographical look into the aging poet’s life. Even with old age, and surviving a stroke in 1873, Whitman never stopped writing. Moving in to 328 Mickle Street in Camden, New Jersey, “Whitman retained the structure of Leaves of Grass, relegating the poetry written after 1881 to appendices—or, as the poet called them, annexes—to the main book” (Folsom & Price). The poems in his annexes are shorter, more reflective, and give insight into the mind of someone knocking on death’s door and questioning their after-life. While Whitman was growing more immobile and gray, America was becoming more of an industrial giant. American society quickly changed becoming more economically wealthy and diverse with this industrial growth. Although America was no longer broken by the Civil War, Whitman was still haunted by this harrowing time in his life and his poetry still reflects this troublesome period in American history. As Folsom and Price note, “Whitman continued writing, ‘garrulous’ to the very end, but he worried that, because of his relative longevity, ‘Ungracious glooms, aches, lethargy, constipation, whimpering ennui, / May filter in my daily songs.”

Halcyon Days

“As gorgeous, vapory, silent hues cover the evening sky, As softness, fulness, rest, suffuse the frame, like freshier, balmier air, As the days take on a mellower light, and the apple at last hangs really finish’d and indolent-ripe on the tree”

Published in 1888, “Halcyon Days” is a part of Whitman’s “Sands at Seventy” cluster of his first Annex to the final edition of Leaves of Grass. As David Baldwin writes in his commentary on the poem, “Whitman contrasts the usual great rewards in life (“successful” love, wealth, honor, fame) with what he sees as greater rewards “as life wanes,” paralleling nature’s quieter moods in the autumn or at day’s end with the same condition in old age.” This photo was taken from the rooftop of one of Downtown Charleston’s many parking garages and the ethereal sun setting in the distant sky. Like Whitman’s poem, this photo conjures the “brooding and blissful” imagery to which Whitman describes. As the sun sets in the sky, so too does Whitman’s life.

Continuities

“The body, sluggish, aged, cold—the embers left from earlier fires, The light in the eye grown dim, shall duly flame again”

Like “Halcyon Days,” “Continuities” was published in 1888 as a part of Whitman’s “Sands at Seventy” cluster in his first annex. As the inscription below the title suggests, this poem was born out of a conversation Whitman had with a German spiritualist and deals with Life, Identity, and Man’s relationship with Nature. For someone like Whitman who was in the final years of his life, it shows the resilience he had in life as a man and a writer despite everything he had witnessed in his older age. The photo embodies this idea of embers lost in time “shall duly flame again.” It is a raging fire which fills the space around it, unafraid of what lies ahead or being put out. Despite everything Whitman experienced, this photo and the poem represents a recognition of and a wish to harken back to the Whitman of his younger years, full of Romantic passion and joy at the world around him.

To the Sun-Set Breeze

“(Thou hast, O Nature! elements! utterance to my heart beyond the rest—and this is of them,) So sweet thy primitive taste to breathe within—thy soothing fingers my face and hands”

“To the Sun-Set Breeze” was published in 1890 in “Good-bye my Fancy” from Whitman’s Second Annex to his final publication of Leaves of Grass. Whitman, now “old, sick, weak-down, melted-worn with sweat” has one of his final experiences with Nature in the twilight of his life. Whitman is overwhelmed by the awe-inspiring and mighty elements of Nature from the sky to the prairies and ocean. This photo was taken at Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina and creates this feeling of haunting beauty ever present in Nature, as Whitman says, “thou, hast, O Nature! Elements.” The imagery of the multitude of plants blowing in the wind showcase the power of Nature. It is overwhelming in its intensity and display and Whitman is taken over by the emotion evoked by this divine grandeur.

The Pallid Wreath

“One wither’d rose put years ago for thee, dear friend, But I do not forget thee. Hast thou then faded? Is the odor exhaled? Are the colors, vitalities, dead? No, while memories subtly play—the past vivid as ever”

Published a year before his death in 1891, “The Pallid Wreath” was a part of Whitman’s cluster in his Second Annex called “Good-bye my Fancy”. Similar to “Continuities,” there is a liveliness to this poem despite Whitman being near the end of his life. Unlike the Civil War where he could not see past the myriad of dead soldiers before him, there is a shift in this poem towards the negative sublime. Seeing the vacant life of the rose and wreath before him, Whitman cannot help but look past their exterior “gray and ashy” colors and know that even in this state, they are “not yet dead to [him].” The vibrancy of the dying rose in the photo imitates this same feeling described by Whitman. Even as the flower begins to wither and die, its colors stand out amongst the drab space it resides in and shows how even as time ages all things, like Whitman himself, “the past [is still] vivid as ever.”

Works Cited

Asselineau, Roger. The Evolution of Walt Whitman: An Expanded Edition (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1999).

Baldwin, David B. “The Walt Whitman Archive.” David B. Baldwin, “Halcyon Days” (Criticism) – The Walt Whitman Archive, 1998, https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_472.html.

Drake, Alan D. “Walt Whitman – Song of Myself and Other Poems : Alan Davis Drake : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/WaltWhitman-SongOfMyselfAndOtherPoems.

Folsom, Ed. “The Walt Whitman Archive.” Ed Folsom, “Photographs and Photographers” (Criticism) – The Walt Whitman Archive, 1998, https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_592.html.

Folsom, Ed, and Kenneth M. Price. “The Walt Whitman Archive.” Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, “Walt Whitman” – The Walt Whitman Archive, https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/walt_whitman/index.html#origins.

Gerhardt, Christine. A Place for Humility: Whitman, Dickinson, and the Natural World (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014).

Killingsworth, M. Jimmie. Walt Whitman and the Earth: A Study in Ecopoetics (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2004).

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman. Oxford University Press, 2005. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=120947&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Smeller, Carl. “The Walt Whitman Archive.” Carl Smeller, “I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing (1860)” (Criticism) – The Walt Whitman Archive, 1998, https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_490.html.

U.S. Timeline, The 1850s – America’s Best History, https://americasbesthistory.com/abhtimeline1850.html.

No comments yet.