Modi is a lifelong member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a paramilitary Hindu nationalist organisation inspired by the fascist movements of Europe, whose founder’s belief that Nazi Germany had manifested “race pride at its highest” by purging the Jews is by no means unexceptional among the votaries of Hindutva, or “Hinduness”. In 1948, a former member of the RSS murdered Gandhi for being too soft on Muslims. The outfit, traditionally dominated by upper-caste Hindus, has led many vicious assaults on minorities. A notorious executioner of dozens of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 crowed that he had slashed open with his sword the womb of a heavily pregnant woman and extracted her foetus. Modi himself described the relief camps housing tens of thousands of displaced Muslims as “child-breeding centres”.

Such rhetoric has helped Modi sweep one election after another in Gujarat. A senior American diplomat described him, in cables disclosed by WikiLeaks, as an “insular, distrustful person” who “reigns by fear and intimidation”; his neo-Hindu devotees on Facebook and Twitter continue to render the air mephitic with hate and malice, populating the paranoid world of both have-nots and haves with fresh enemies – “terrorists”, “jihadis”, “Pakistani agents”, “pseudo-secularists”, “sickulars”, “socialists” and “commies”. Modi’s own electoral strategy as prime ministerial candidate, however, has been more polished, despite his appeals, both dog-whistled and overt, to Hindu solidarity against menacing aliens and outsiders, such as the Italian-born leader of the Congress party, Sonia Gandhi, Bangladeshi “infiltrators” and those who eat the holy cow.

Modi exhorts his largely young supporters – more than two-thirds of India’s population is under the age of 35 – to join a revolution that will destroy the corrupt old political order and uproot its moral and ideological foundations while buttressing the essential framework, the market economy, of a glorious New India. In an apparently ungovernable country, where many revere the author of Mein Kampf for his tremendous will to power and organisation, he has shrewdly deployed the idioms of management, national security and civilisational glory.

Boasting of his 56-inch chest, Modi has replaced Mahatma Gandhi, the icon of non-violence, with Vivekananda, the 19th-century Hindu revivalist who was obsessed with making Indians a “manly” nation. Vivekananda’s garlanded statue or portrait is as ubiquitous in Modi’s public appearances as his dandyish pastel waistcoats. But Modi is never less convincing than when he presents himself as a humble tea-vendor, the son-of-the-soil challenger to the Congress’s haughty dynasts. His record as chief minister is predominantly distinguished by the transfer – through privatisation or outright gifts – of national resources to the country’s biggest corporations. His closest allies – India’s biggest businessmen – have accordingly enlisted their mainstream media outlets into the cult of Modi as decisive administrator; dissenting journalists have been removed or silenced.

Not long after India’s first full-scale pogrom in 2002, leading corporate bosses, ranging from the suave Ratan Tata to Mukesh Ambani, the owner of a 27-storey residence, began to pave Modi’s ascent to respectability and power. The stars of Bollywood fell (literally) at the feet of Modi. In recent months, liberal-minded columnists and journalists have joined their logrolling rightwing compatriots in certifying Modi as a “moderate” developmentalist. The Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati, who insists that he intellectually fathered India’s economic reforms in 1991, and Gurcharan Das, author of India Unbound, have volunteered passionate exonerations of the man they consider India’s saviour.

Absurdly uneven and jobless economic growth has led to what Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze call “islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa”. The failure to generate stable employment – 1m new jobs are required every month – for an increasingly urban and atomised population, or to allay the severe inequalities of opportunity as well as income, created, well before the recent economic setbacks, a large simmering reservoir of rage and frustration. Many Indians, neglected by the state, which spends less proportionately on health and education than Malawi, and spurned by private industry, which prefers cheap contract labour, invest their hopes in notions of free enterprise and individual initiative. However, old and new hierarchies of class, caste and education restrict most of them to the ranks of the unwashed. As the Wall Street Journal admitted, India is not “overflowing with Horatio Alger stories”. Balram Halwai, the entrepreneur from rural India in Aravind Adiga’s Man Booker-winning novel The White Tiger, who finds in murder and theft the quickest route to business success and self-confidence in the metropolis, and Mumbai’s social-Darwinist slum-dwellers in Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers point to an intensified dialectic in India today: cruel exclusion and even more brutal self-empowerment.

❦

Such extensive moral squalor may bewilder those who expected India to conform, however gradually and imperfectly, to a western ideal of liberal democracy and capitalism. But those scandalised by the lure of an indigenised fascism in the country billed as the “world’s largest democracy” should know: this was not the work of a day, or of a few “extremists”. It has been in the making for years. “Democracy in India,” BR Ambedkar, the main framer of India’s constitution, warned in the 1950s, “is only a top dressing on an Indian soil, which is essentially undemocratic.” Ambedkar saw democracy in India as a promise of justice and dignity to the country’s despised and impoverished millions, which could only be realised through intense political struggle. For more than two decades that possibility has faced a pincer movement: a form of global capitalism that can only enrich a small minority and a xenophobic nationalism that handily identifies fresh scapegoats for large-scale socio-economic failure and frustration.

In many ways, Modi and his rabble – tycoons, neo-Hindu techies, and outright fanatics – are perfect mascots for the changes that have transformed India since the early 1990s: the liberalisation of the country’s economy, and the destruction by Modi’s compatriots of the 16th-century Babri mosque in Ayodhya. Long before the killings in Gujarat, Indian security forces enjoyed what amounted to a licence to kill, torture and rape in the border regions of Kashmir and the north-east; a similar infrastructure of repression was installed in central India after forest-dwelling tribal peoples revolted against the nexus of mining corporations and the state. The government’s plan to spy on internet and phone connections makes the NSA’s surveillance look highly responsible. Muslims have been imprisoned for years without trial on the flimsiest suspicion of “terrorism”; one of them, a Kashmiri, who had only circumstantial evidence against him, was rushed to the gallows last year, denied even the customary last meeting with his kin, in order to satisfy, as the supreme court put it, “the collective conscience of the people”.

“People who were not born then,” Robert Musil wrote in The Man Without Qualities of the period before another apparently abrupt collapse of liberal values, “will find it difficult to believe, but the fact is that even then time was moving faster than a cavalry camel … But in those days, no one knew what it was moving towards. Nor could anyone quite distinguish between what was above and what was below, between what was moving forward and what backward.” One symptom of this widespread confusion in Musil’s novel is the Viennese elite’s weird ambivalence about the crimes of a brutal murderer called Moosbrugger. Certainly, figuring out what was above and what was below is harder for the parachuting foreign journalists who alighted upon a new idea of India as an economic “powerhouse” and the many “rising” Indians in a generation born after economic liberalisation in 1991, who are seduced by Modi’s promise of the utopia of consumerism – one in which skyscrapers, expressways, bullet trains and shopping malls proliferate (and from which such eyesores as the poor are excluded).

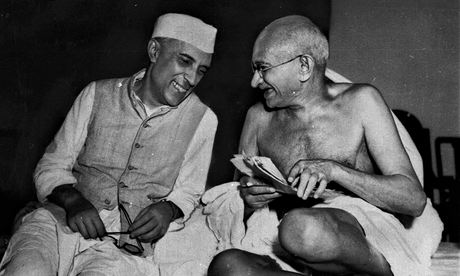

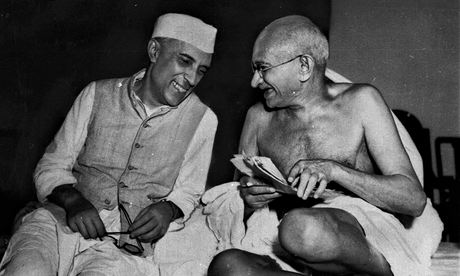

A civilising mission … Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi. Photograph: Max Desfor/AP ❦

A civilising mission … Jawaharlal Nehru with Mahatma Gandhi. Photograph: Max Desfor/AP ❦

People who were born before 1991, and did not know what time was moving towards, might be forgiven for feeling nostalgia for the simpler days of postcolonial idealism and hopefulness – those that Seth evokes in A Suitable Boy. Set in the 1950s, the novel brims with optimism about the world’s most audacious experiment in democracy, endorsing the Nehruvian “idea of India” that seems flexible enough to accommodate formerly untouchable Hindus (Dalits) and Muslims as well as the middle-class intelligentsia. The novel’s affable anglophone characters radiate the assumption that the sectarian passions that blighted India during its partition in 1947 will be defused, secular progress through science and reason will eventually manifest itself, and an enlightened leadership will usher a near-destitute people into active citizenship and economic prosperity.

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, appears in the novel as an effective one-man buffer against Hindu chauvinism. “The thought of India as a Hindu state, with its minorities treated as second-class citizens, sickened him.” In Nehru’s own vision, grand projects such as big dams and factories would bring India’s superstitious masses out of their benighted rural habitats and propel them into first-world affluence and rationality. The Harrow- and Cambridge-educated Indian leader had inherited from British colonials at least part of their civilising mission, turning it into a national project to catch up with the industrialised west. “I was eager and anxious,” Nehru wrote of India, “to change her outlook and appearance and give her the garb of modernity.” Even the “uninteresting” peasant, whose “limited outlook” induced in him a “feeling of overwhelming pity and a sense of ever-impending tragedy” was to be present at what he called India’s “tryst with destiny”.

That long attempt by India’s ruling class to give the country the “garb of modernity” has produced, in its sixth decade, effects entirely unanticipated by Nehru or anyone else: intense politicisation and fierce contests for power together with violence, fragmentation and chaos, and a concomitant longing for authoritarian control. Modi’s image as an exponent of discipline and order is built on both the successes and failures of the ancien regime. He offers top-down modernisation, but without modernity: bullet trains without the culture of criticism, managerial efficiency without the guarantee of equal rights. And this streamlined design for a new India immediately entices those well-off Indians who have long regarded democracy as a nuisance, recoiled from the destitute masses, and idolised technocratic, if despotic, “doers” like the first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew.

But then the Nehruvian assumption that economic growth plotted and supervised by a wise technocracy would also bring about social change was also profoundly undemocratic and self-serving. Seth’s novel, along with much anglophone literature, seems, in retrospect, to have uncritically reproduced the establishment ideology of English-speaking and overwhelmingly upper-caste Hindus who gained most from state-planned economic growth: the Indian middle class employed in the public sector, civil servants, scientists and monopolist industrialists. This ruling class’s rhetoric of socialism disguised its nearly complete monopoly of power. As DR Nagaraj, one of postcolonial India’s finest minds, pointed out, “the institutions of capitalism, science and technology were taken over by the upper castes”. Even today, businessmen, bureaucrats, scientists, writers in English, academics, thinktankers, newspaper editors, columnists and TV anchors are disproportionately drawn from among the Hindu upper-castes. And, as Sen has often lamented, their “breathtakingly conservative” outlook is to be blamed for the meagre investment in health and education – essential requirements for an equitable society as well as sustained economic growth – that put India behind even disaster-prone China in human development indexes, and now makes it trail Bangladesh.

Dynastic politics froze the Congress party into a network of patronage, delaying the empowerment of the underprivileged Indians who routinely gave it landslide victories. Nehru may have thought of political power as a function of moral responsibility. But his insecure daughter, Indira Gandhi, consumed by Nixon-calibre paranoia, turned politics into a game of self-aggrandisement, arresting opposition leaders and suspending fundamental rights in 1975 during a nationwide “state of emergency”. She supported Sikh fundamentalists in Punjab (who eventually turned against her) and rigged elections in Muslim-majority Kashmir. In the 1980s, the Congress party, facing a fragmenting voter base, cynically resorted to stoking Hindu nationalism. After Indira Gandhi’s assassination by her bodyguards in 1984, Congress politicians led lynch mobs against Sikhs, killing more than 3,000 civilians. Three months later, her son Rajiv Gandhi won elections with a landslide. Then, in another eerie prefiguring of Modi’s methods, Gandhi, a former pilot obsessed with computers, tried to combine technocratic rule with soft Hindutva.

The Bharatiya Janata party (BJP), a political offshoot of the RSS that Nehru had successfully banished into the political wilderness, turned out to be much better at this kind of thing. In 1990, its leader LK Advani rode a “chariot” (actually a rigged-up Toyota flatbed truck) across India in a Hindu supremacist campaign against the mosque in Ayodhya. The wildfire of anti-Muslim violence across the country reaped immediate electoral dividends. (In old photos, Modi appears atop the chariot as Advani’s hawk-eyed understudy). Another BJP chieftain ventured to hoist the Indian tricolour in insurgent Kashmir. (Again, the bearded man photographed helping his doddery senior taunt curfew-bound Kashmiris turns out to be the young Modi.) Following a few more massacres, the BJP was in power in 1998, conducting nuclear tests and fast-tracking the programme of economic liberalisation started by the Congress after a severe financial crisis in 1991.

The Hindu nationalists had a ready consumer base for their blend of chauvinism and marketisation. With India’s politics and economy reaching an impasse, which forced many of their relatives to emmigrate to the US, and the Congress facing decline, many powerful Indians were seeking fresh political representatives and a new self-legitimising ideology in the late 1980s and 90s. This quest was fulfilled by, first, both the post-cold war dogma of free markets and then an openly rightwing political party that was prepared to go further than the Congress in developing close relations with the US (and Israel, which, once shunned, is now India’s second-biggest arms supplier after Russia). You can only marvel today at the swiftness with which the old illusions of an over-regulated economy were replaced by the fantasies of an unregulated one.

Narendra Modi waves to supporters as he rides on an open truck on his way to filing his nomination papers. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images According to the new wisdom – new to India, if already worn out and discredited in Latin America – all governments needed to do was get out of the way of buoyant and autonomous entrepreneurs and stop subsidising the poor and the lazy (in a risible self-contradiction these Indian promoters of minimalist governance also clamoured for a big militarised state apparatus to fight and intimidate neighbours and stifle domestic insurgencies). The long complex experience of strong European as well as east Asian economies – active state intervention in markets and support to strategic industries, long periods of economic nationalism, investments in health and education – was elided in a new triumphalist global history of free markets. Its promise of instant and widespread affluence seemed to have been manufactured especially for gormless journalists and columnists. Still, in the last decade, neoliberalism became the common sense of many Indians who were merely aspiring as well as those who had already made it – the only elite ideology after Nehruvian nation-building to have achieved a high degree of pan-Indian consent, if not total hegemony. The old official rhetoric of egalitarian and shared futures gave way to the media’s celebrations of private wealth-creation – embodied today by Ambani’s 27-storey private residence in a city where a majority lives in slums – and a proliferation of Ayn Randian cliches about ambition, willpower and striving.

Narendra Modi waves to supporters as he rides on an open truck on his way to filing his nomination papers. Photograph: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images According to the new wisdom – new to India, if already worn out and discredited in Latin America – all governments needed to do was get out of the way of buoyant and autonomous entrepreneurs and stop subsidising the poor and the lazy (in a risible self-contradiction these Indian promoters of minimalist governance also clamoured for a big militarised state apparatus to fight and intimidate neighbours and stifle domestic insurgencies). The long complex experience of strong European as well as east Asian economies – active state intervention in markets and support to strategic industries, long periods of economic nationalism, investments in health and education – was elided in a new triumphalist global history of free markets. Its promise of instant and widespread affluence seemed to have been manufactured especially for gormless journalists and columnists. Still, in the last decade, neoliberalism became the common sense of many Indians who were merely aspiring as well as those who had already made it – the only elite ideology after Nehruvian nation-building to have achieved a high degree of pan-Indian consent, if not total hegemony. The old official rhetoric of egalitarian and shared futures gave way to the media’s celebrations of private wealth-creation – embodied today by Ambani’s 27-storey private residence in a city where a majority lives in slums – and a proliferation of Ayn Randian cliches about ambition, willpower and striving.

❦

Nehru’s programme of national self-strengthening had included, along with such ideals as secularism, socialism and non-alignment, a deep-rooted suspicion of American foreign policy and economic doctrines. In a stunning coup, India’s postcolonial project was taken over, as Octavio Paz once wrote of the Mexican revolution, “by a capitalist class made in the image and likeness of US capitalism and dependent upon it”. A new book by Anita Raghavan, The Billionaire’s Apprentice: The Rise of the Indian-American Elite and the Fall of the Galleon Hedge Fund, reveals how well-placed men such as Rajat Gupta, the investment banker recently convicted for insider trading in New York, expedited close links between American and Indian political and business leaders.

India’s upper-caste elite transcended party lines in their impassioned courting of likely American partners. In 2008, an American diplomat in Delhi was given an exclusive preview by a Congress party factotum of two chests containing $25m in cash – money to bribe members of parliament into voting for a nuclear deal with the US. Visiting the White House later that year, Singh blurted out to George W Bush, probably resigned by then to being the most despised American president in history, that “the people of India love you deeply”. In a conversation disclosed by WikiLeaks, Arun Jaitley, a senior leader of the BJP who is tipped to be finance minister in Modi’s government, urged American diplomats in Delhi to see his party’s anti-Muslim rhetoric as “opportunistic”, a mere “talking point” and to take more seriously his own professional and emotional links with the US.

A transnational elite of rightwing Indians based in the US helped circulate an impression of an irresistibly “emerging giant” – the title of a book by Arvind Panagariya, a New-York-based economist and another aspiring adviser to Modi. Very quickly, the delusional notion that India was, as Foreign Affairs proclaimed on its cover in 2006, a “roaring capitalist success-story” assumed an extraordinary persuasive power. In India itself, a handful of corporate acquisitions – such as Tata’s of Jaguar and Corus – stoked exorbitant fantasies of an imminent “Global Indian Takeover” (the title of a regular feature once in India’s leading business daily, the Economic Times). Rent-seekers in a shadow intellectual economy – thinktank-sailors, bloggers and Twitterbots – as well as academics perched on corporate-endowed chairs recited the mantra of privatisation and deregulation in tune. Nostrums from the Reagan-Thatcher era – the primary source of ideological self-indoctrination for many Americanised Indians – about “labour flexibility” were endlessly regurgitated, even though a vast majority of the workforce in India – more than 90% – toils in the unorganised or “informal” sector. Bhagwati, for instance, hailed Bangladesh for its superb labour relations a few months before the collapse of the Rana Plaza in Dhaka; he also speculated that the poor “celebrate” inequality, and, with Marie Antoinette-ish serenity, advised malnourished families to consume “more milk and fruits”. Confronted with the World Health Organisation’s extensive evidence about malnutrition in India, Panagariya, ardent patron of the emerging giant, argued that Indian children are genetically underweight.

❦

This pitiless American free-marketeering wasn’t the only extraordinary mutation of Indian political and economic discourse. By 1993, when A Suitable Boy was published, the single-party democracy it describes had long been under siege from low-caste groups and a rising Hindu-nationalist middle class. (Sunil Khilnani’s The Idea of India, the most eloquent defence and elaboration of India’s foundational ideology, now seems another posthumous tribute to it.) India after Indira Gandhi increasingly failed to respect the Nehruvian elite’s coordinates of progress and order. Indian democracy, it turned out, had seemed stable only because political participation was severely limited, and upper-caste Hindus effectively ran the country. The arrival of low-caste Hindus in mass politics in the 1980s, with their representatives demanding their own share of the spoils of power, put the first strains on the old patrimonial system. Upper-caste panic initially helped swell the ranks of the BJP, but even greater shifts caused by accelerating economic growth after 1991 have fragmented even relatively recent political formations based on caste and religion.

Rapid urbanisation and decline of agriculture created a large mass of the working poor exposed to ruthless exploitation in the unorganised sector. Connected to their homes in the hinterland through the flow of remittances, investment, culture and ideas, these migrants from rural areas were steadily politically awakened with the help of print literacy, electronic media, job mobility and, most importantly, mobile phones (subscribers grew from 45 million in 2002 to almost a billion in 2012). The Congress, though instrumentally social-welfarist while in power, failed to respond to this electorally consequential blurring of rural and urban borderlines, and the heightened desires for recognition and dignity as well as for rapid inclusion into global modernity. Even the BJP, which had fed on upper-caste paranoia, had been struggling under its ageing leaders to respond to an increasingly demanding mass of voters after its initial success in the 1990s, until Modi reinvented himself as a messiah of development, and quickly found enlarged constituencies – among haves as well as have-nots – for his blend of xenophobia and populism.

A wave of political disaffection has also deposited democratic social movements and dedicated individuals across the country. Groups both within and outside the government, such as those that successfully lobbied for the groundbreaking Right to Information Act, are outlining the possibilities of what John Keane calls “monitory democracy”. India’s many activist networks – for the rights of women, Dalits, peasants and indigenous communities – or issue-based campaigns, such as those against big dams and nuclear power plants, steer clear of timeworn ideas of national security, economic development, technocratic management, whether articulated by the Nehruvians or the neo-Hindus. In a major environment referendum last year, residents of small tribal hamlets in a remote part of eastern India voted to reject bauxite mining in their habitats. Growing demands across India for autonomy and bottom-up governance confirm that Modi is merely offering old – and soured – lassi in new bottles with his version of top-down modernisation.

Modi, however, has opportunely timed his attempt to occupy the commanding heights of the Indian state vacated by the Congress. The structural problems of India’s globalised economy have dramatically slowed its growth since 2011, terminating the euphoria over the Global Indian Takeover. Corruption scandals involving the sale of billions of dollars’ worth of national resources such as mines, forests, land, water and telecom spectrums have revealed that crony capitalism and rent-seeking were the real engines of India’s economy. The beneficiaries of the phenomenon identified by Arundhati Roy as “gush-up” have soared into a transnational oligarchy, putting the bulk of their investments abroad and snapping up, together with Chinese and Russian plutocrats, real estate in London, New York and Singapore. Meanwhile, those made to wait unconscionably long for “trickle-down” – people with dramatically raised but mostly unfulfillable aspirations – have become vulnerable to demagogues promising national regeneration. It is this tiger of unfocused fury, spawned by global capitalism in the “underdeveloped” world, that Modi has sought to ride from Gujarat to New Delhi.

❦

“Even in the darkest of times,” Hannah Arendt once wrote, “we have the right to expect some illumination.” The most prominent Indian institutions and individuals have rarely obliged, even as the darkness of the country’s atrocity-rich borderlands moved into the heartland. Some of the most respected commentators, who are often eloquent in their defence of the right to free speech of famous writers, maintained a careful silence about the government’s routine strangling of the internet and mobile networks in Kashmir. Even the liberal newspaper the Hindu prominently featured a journalist who retailed, as an investigation in Caravan revealed, false accusations of terrorism against innocent citizens. (The virtues of intelligence, courage and integrity are manifested more commonly in small periodicals such as Caravan and Economic and Political Weekly, or independent websites such as Kafila.org and Scroll.in.) The owners of the country’s largest English-language newspaper, the Times of India, which has lurched from tedium to decadence within a few years, have innovated a revenue-stream called “paid news”. Unctuously lobbing softballs at Modi, the prophets of electronic media seem, on other occasions, to have copied their paranoid inquisitorial style from Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh. Santosh Desai, one of contemporary India’s most astute observers, correctly points out that the “intolerance that one sees from a large section of society is in some way a product of a ‘televisionised’ India. The pent-up feelings of resentment and entitlement have rushed out and get both tacit and explicit support from television.”

A spate of corporate-sponsored literary festivals did not compensate for the missing culture of debate and reflection in the press. The frothy glamour of these events may have helped obscure the deeper intellectual and cultural churning in India today, the emergence of writers and artists from unconventional class and caste backgrounds, and the renewed attention to BR Ambedkar, the bracing Dalit thinker obscured by upper-caste iconographies. The probing work of, among others, such documentary film-makers as Anand Patwardhan (Jai Bhim Comrade), Rahul Roy (Till We Meet Again), Rakesh Sharma (Final Solution) and Sanjay Kak (Red-Ant Dream), and members of the Raqs Media Collective outlines a modernist counterculture in the making.

But the case of Bollywood shows how the unravelling of the earliest nation-building project can do away with the stories and images through which many people imagined themselves to be part of a larger whole, and leave only tawdriness in its place. Popular Hindi cinema degenerated alarmingly in the 1980s. Slicker now, and craftily aware of its non-resident Indian audience, it has become an expression of consumer nationalism and middle-class self-regard; Amitabh Bachchan, the “angry young man” who enunciated a widely felt victimhood during a high point of corruption and inflation in the 1970s, metamorphosed into an avuncular endorser of luxury brands. A search for authenticity, and linguistic vivacity, has led film-makers back to the rural hinterland in such films as Gangs of Wasseypur, Peepli Live and Ishqiya, whose flaws are somewhat redeemed by their scrupulous avoidance of Indians sporting Hermès bags or driving Ferraris. Some recent breakthroughs such as Anand Gandhi’s Ship of Theseus and Dibakar Banerji’s Costa-Gavras-inspired Shanghai gesture to the cinema of crisis pioneered by Asian, African and Latin American film-makers. But India’s many film industries have yet to produce anything that matches Jia Zhangke‘s unsentimental evocations of China’s past and present, the acute examination of middle-class pathologies in Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighbouring Sounds, or Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s delicate portrait of the sterile secularist intellectual in Uzak.

❦

The long artistic drought results partly from the confusion and bewilderment of an older, entrenched elite, the main producers, until recently, of mainstream culture. With their prerogative to rule and interpret India pilfered by the “unwashed” and the “gullible”, the anglophones have been struggling to grasp the eruption of mass politics in India, its new centrifugal thrust, and the nature of the challenge posed by many apparently illiberal individuals and movements. It is easy for them to denounce India’s evidently uncouth retailers of caste and religious identity as embodiments of, in Salman Rushdie’s words, “Caligulan barbarity”; or to mock Chetan Bhagat, the bestselling author of novels for young adults and champion tweeter, for boasting of his “selfie” with Modi. Those pied-pipering the young into Modi-mania nevertheless possess the occult power to fulfil the deeper needs of their needy followers. They can compile vivid ideological collages – made of fragments of modernity, glimpses of utopia and renovated pieces of a forgotten past. It is in the “mythological thrillers” and positive-thinking fictions – the most popular literary genres in India today – that a post-1991 generation that doesn’t even know it is lost fleetingly but thrillingly recognises itself.

In a conventional liberal perspective, these works may seem like hotchpotches, full of absurd contradictions that confound the “above” with the “below”, the “forward” with the “backward”. Modi, for instance, consistently mixes up dates and historical events, exposing an abysmal ignorance of the past of the country he hopes to lead into a glorious future. Yet his lusty hatred of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty excites many young Indians weaned on the neo-liberal opiates about aspiration and merit. And he combines his historical revisionism and Hindu nationalism with a revolutionary futurism. He knows that resonant sentiments, images, and symbols – Vivekananda plus holograms and Modi masks – rather than rational argument or accurate history galvanise individuals. Vigorously aestheticising mass politics, and mesmerising the restless young, he has emerged as the new India’s canniest artist.

But, as Walter Benjamin pointed out, rallies, parades and grand monuments do not secure the masses their rights; they give them no more than the chance to express themselves, and noisily identify with an alluring leader and his party. It seems predictable that Modi will gratify only a few with his ambitious rescheduling of India’s tryst with destiny. Though many exasperated Indians see Modi as bearing the long-awaited fruits of the globalised economy, he actually embodies its inevitable dysfunction. He resembles the European and Japanese demagogues of the early 20th century who responded to the many crises of liberalism and democracy – and of thwarted nation-building and modernisation – by merging corporate and political power, and exhorting communal unity before internal and external threats. But Modi belongs also to the dark days of the early 21st century.

His ostensibly gratuitous assault on Muslims – already India’s most depressed and demoralised minority – was another example of what the social anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls “a vast worldwide Malthusian correction, which works through the idioms of minoritisation and ethnicisation but is functionally geared to preparing the world for the winners of globalisation, minus the inconvenient noise of its losers”. Certainly, the new horizons of desire and fear opened up by global capitalism do not favour democracy or human rights. Other strongmen who supervised the bloody purges of economically enervated and unproductive people were also ruthless majoritarians, consecrated by big election victories. The crony-capitalist regimes of Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand and Vladimir Putin in Russia were inaugurated by ferocious offensives against ethnic minorities. The electorally bountiful pogrom in Gujarat in 2002, too, now seems an early initiation ritual for Modi’s India.

The difficulty of assessing his personal culpability in the killings and rapes of 2002 is the same difficulty that Musil identifies with Moosbrugger in his novel: how to measure the crimes, however immense, of individuals against a universal breakdown of values and the normalisation of violence and injustice. “If mankind could dream collectively,” Musil writes, “it would dream Moosbrugger.” There is little cause yet for such despair in India, where the aggrieved fantasy of authoritarianism will have to reckon with the gathering energies below; the great potential of the country’s underprivileged and voiceless peoples still lies untapped. But for now some Indians have dreamed collectively, and they have dreamed a man accused of mass murder.