Ellen Gwin

Dr. Anton Vander Zee

American Poetry

18 October 2022

Sticky Labels

Danez Smith, author of Don’t Call us Dead (2017), Boy (2014) and the chapbook hands on ya knees (2013), is an African American writer from St. Paul, Minnesota. They are a founding member of the Dark Noise Collective, a multi-genre, multicultural collective focused on identity, intersectionality, trauma, and healing. Although Smith is originally from Minnesota, their family is from Mississippi and Georgia— two states with a significant population of black people and who harbor history of racism which leak into the present as institutionalized racism (Danez Smith).

The poem “alternate names for black boys” by Danez Smith details a list of different phrases black men have been associated with by society or phrases that express ideologies that society associates with black men. Although the phrase is specifically titled supposedly for “black boys,” I feel this is a poem for all black people. I also feel like the title itself is a play on the infantilization of black men in society where many older white men refer to black, male adults as “black boys.” By calling black men “black boys” their accomplishments and maturity level gets diminished. I feel like a good example of this is Chesterton’s Uncle Remus as well as the depiction of Liam in the TV show Shameless.

I decided to interpret the first seven phrases on the list in the poem in a blog-like spirit. Danez Smith’s lines will be in bold with my interpretation underneath.

“1. smoke above the burning bush”

The smoke does not cause smoke, but still smoke still remains the thing everyone feels annoyed about– the smell, the invasive nature of smoke, the lingering — but still the fire causes the smoke. And what of the bush? And those who fuel the fire? They should be held accountable too.

A black man is compared to this smoke. I believe this calls to the ideology of institutionalized racism. For example, statistically a lot of black men are in jail, black people represent 12% of the U.S. adult population but 33% of the jail population (Gramlich), and therefore labeled as criminals, but what causes have created a situation where that may has become a reality? What fuels these causes and these situations?

Kevin Coval calls attention to this reality when referring to the “school-to-prison” pipeline (The Breakbeat Poets xix).

“2. archnemesis of summer night”

Seeing this man is from the South I cannot help but project my own hell-ish sense of summer onto this line (I actually have written multiple poems about it). This hell-ish idea of summer combined with the ideas surrounding darkness and night makes me feel that the speaker wants to depict black boys as the friends of winter– the friends of somewhere cooler or someone cool.

I feel like there is more to this line I’m not understanding and I keep trying to stretch. Part of me wants to say this is about sundown towns in the South (a warmer place) then the other part of me feels like this may reference the frequency of lynchings and false accusations that would occur in the night. My last thought is that black people have darker skin and therefore cannot be seen in the night as easily as white people’s skin.

“3. first son of soil”

This speaks to a man who was born in the dirt.

The African Diaspora forced slaves into agricultural work, work white men/people were not doing, making black people the first people to work the soil, the first sons.

I think a brilliant play on words could be had here, especially in regards to Adam and Lilith who were the first humans on earth and both made from dirt (clay) as equals but not treated as such.

“4. coal awaiting spark & wind”

This line depicts the idea of how a small spark can start a whole wildfire.

Society has a habit of keeping black men and people down, destroying any spark of creativity or stealing it and calling it their own (i.e. like the entire fashion industry @HaileyBieber @UrbanOutfitters).

I also found this line in particular in conjunction with the title when aligned with the current trend of depicting “black boy joy.”

“5. guilty until proven dead”

The idea that, despite how black people may live day to day, they are labeled as criminals and therefore have a higher rate of being killed by either vigilantes, police, or by the prison system.

By contrast, despite how white people may live day to day, they are not labeled as criminals and do not become targeted by the social justice system and therefore have a higher rate of living in America.

“6. oil heavy starlight”

I feel like there’s a more accurate interpretation, but this to me reminds me of when students would make fun of black people’s hair. Black people have a naturally high porosity hair calling for more oils and conditioners, combine that with trying to fit into white beauty standards, that’s a lot of oil and grease going into the hair. Combining this idea with starlight make me feel like this idea speaks to how weight of white beauty standards caused black people (starlights) to feel.

“7. monster until proven ghost”

Black people as monstrous, violent, or angry until dead and memorialized.

This could also be a comparison to the “oreo” ideology: a black person is accepted in society if they “act white.” If a black person seems white like a ghost, they may not be considered a monster.

Although the lines are short, the rest of the ten phrases each have their own eye-opening ideology within and deserve their own special attention, I definitely encourage everyone to go in and give them a look if they have not!

Discussion

What are some of your interpretations of these phrases? Are they different?

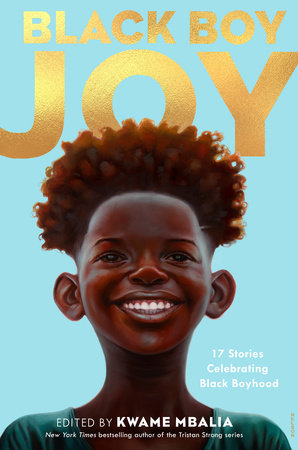

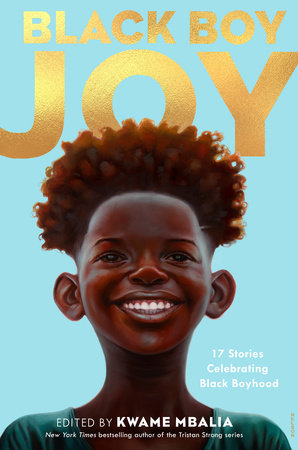

Also, in my research I found this book edited by Kwame Mbalia that depicts stories that celebrate black boyhood:

Works Cited:

“Danez Smith.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/danez-smith.

No comments yet.