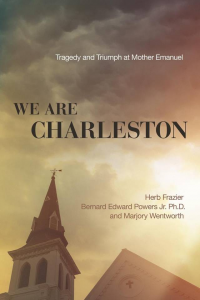

By Bernard Powers, September 19, 2017. This post is part of our series Narratives of the South: Traditions, Transformations, Intersections.

The 2015 racially motivated murders in Charleston’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church and the subsequent removal of the Confederate flag from our Statehouse grounds intensified the already simmering debate over the place of Confederate statues, images and names in the public square. The events in New Orleans and especially Charlottesville have roused passions even further, especially in the South, forcing communities to reconcile their stated values of the present, with a built environment deeply rooted in values of an oppressive past. In Charleston, Mayor Tecklenburg recently charged the city History Commission with changing the signage at Confederate-era and other historic monuments, so that they are “complete and truthful about our history and add context.” He also indicated that additional monuments should be erected to recognize African Americans’ contributions to the city and state. Although these are moderate proposals, it is amazing how threatening they are to many white southerners and how deeply invested these people are in maintaining a racist status quo.

In a recent letter to the editor published by the Charleston Post and Courier under the heading of “Leave statues alone,” the writer criticized the Mayor for seeking to reexamine the messages Confederate-era statues convey, to “create a more balanced narrative.” The writer insisted the real goal was to denigrate the Confederate heritage, while “restricting historic interpretation to a prescribed way of thinking” that favors one group of people. The evidence offered was the city’s Denmark Vesey statue that depicts him as a hero, rather than the “hateful man [he was] who planned widespread murder of Charleston’s white population. . . .[including] ancestors of many of us who live here today.” In several important ways this letter is a case study of how personal feelings and prejudices combine to distort and misrepresent what ought to be our shared history.

As a professional historian who was involved in the Vesey Monument Project, I know there is no credible evidence that Denmark Vesey hated whites or that this was a factor in his conspiracy. Even if true, this assertion would be irrelevant. The writer assumes that enslaved people could have achieved freedom in some non-violent way in 1820s Charleston. Even as a free man Vesey had few rights, and slaves were considered property. Could they have voted their way to freedom? Of course not. Maybe a sit-in or a boycott? We know the white violence those strategies elicited during the later civil rights era. The harsh truth of American history that so many refuse to face today was pronounced by the Supreme Court in 1857. In the Dred Scott Decision, Chief Justice Roger Taney declared that even if free, black people could not be citizens of the United States and were not entitled to its protections; they “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Years later, speaking about how societal change occurs, and describing groups far less oppressed than American slaves, President Kennedy presciently observed: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.” This is precisely what white Carolinians had done. The text of the Vesey statue implies violence on the part of the conspirators, making it more honest than most Confederate-era monuments. The slave rebels expected to resort to violence because whites would certainly have acted ruthlessly to prevent black people from becoming free. Violence as a tool of liberation was legitimately wielded by Anglo-American colonists against Britain’s attempt to crush the American Revolution and, during World War II, by Jews in Warsaw and other ghettoes, against the Nazis’ planned genocide. Denmark Vesey wanted all people to be free; his monument states he was motivated by the “universality of men and women’s desire for freedom and justice, irrespective of race, creed, condition, or color.”

The letter-writer expressed concerns about his ancestors who might have died if Vesey’s conspiracy was actualized. Well, none of them did, because the plans were never fulfilled. However, in Charleston with its high incidence of slaveholding, whites generally endorsed and in multiple ways profited from a system that actually extorted labor by force, destroyed black families and kept people in inhumane and even deadly conditions. In fact, South Carolina was the last state to end the barbaric Atlantic slave trade; when black bodies were consumed they were replaced by new ones from across the Atlantic. Throughout the eighteenth century and as late as the early nineteenth, many whites had such little regard for slaves who died here, that they disposed of black corpses in the waters off the peninsula, eliciting condemnation from local officials. John C. Calhoun, whose statue sits on a high pedestal in Charleston’s Marion Square, provided political and intellectual support for this system, and the Confederate Defenders of Charleston Monument is dedicated to those who shed their blood for it. Black lives did not matter to them; only white lives did.

In June 2015 some relatives of the Emanuel Nine murder victims captured the world’s attention by extending forgiveness to the neo-Confederate murderer of their family members. This was at once an act of Christian charity and self-healing, which won the admiration of many. When black people are forgiving, they always win the plaudits of whites. On the other hand, when they vow, as Denmark Vesey did, to become free “by any means necessary,” even when pushed to the brink by racial proscription and oppression, white critics emerge. We must recognize that Vesey’s decision to fight for freedom was as worthy of emulation as that of George Washington and Patrick Henry and as legitimate as that of the Emanuel Nine family members. We must also cut through the comfortable preoccupation so many have with the “Lost Cause,” emphasizing the valor of Confederates on the battlefield; we should forthrightly consider what kind of society a Confederate victory would have perpetuated and even expanded. Until we can examine these issues and their implications honestly, we cannot have a shared history, nor will we agree on how it should be depicted in the landscape.

In June 2015 some relatives of the Emanuel Nine murder victims captured the world’s attention by extending forgiveness to the neo-Confederate murderer of their family members. This was at once an act of Christian charity and self-healing, which won the admiration of many. When black people are forgiving, they always win the plaudits of whites. On the other hand, when they vow, as Denmark Vesey did, to become free “by any means necessary,” even when pushed to the brink by racial proscription and oppression, white critics emerge. We must recognize that Vesey’s decision to fight for freedom was as worthy of emulation as that of George Washington and Patrick Henry and as legitimate as that of the Emanuel Nine family members. We must also cut through the comfortable preoccupation so many have with the “Lost Cause,” emphasizing the valor of Confederates on the battlefield; we should forthrightly consider what kind of society a Confederate victory would have perpetuated and even expanded. Until we can examine these issues and their implications honestly, we cannot have a shared history, nor will we agree on how it should be depicted in the landscape.

Bernard Powers, Department of History

A shorter version of this essay appeared in the Charleston Post & Courier on September 15, 2017.

Video: Attendees applaud the unveiling of the Denmark Vesey statue in Hampton Park, February 2014.