When reading texts like Piers Plowman and Sir Gawain and the Green Night in their original language, I can’t help but get frustrated when trying to decipher what the modern English word would be. It honestly amazes me how much English has changed over time. The differences between Old English and modern English are so diverse that it is hard to believe that they are the same language.

I took English 309 (English Language-Grammar and History) last semester, and thank God I did, because it really helped me learn the Old English alphabet. However, it makes me wonder what our English language will become in the next 100 years. If English changes so much from 1300 to now, how different will it be in 2116. Will English consist of abbreviations? Will English engulf another language like it did with French and Latin?

As humans, we innately choose the easiest and most efficient way of doing something. The same is true for language. According to the Ease of Articulation Principle, humanity always finds a way to change the sound of a word in a way that is easier to pronounce. This is why Old English and Modern English are so aesthetically different. Why Old English started out in such a complicated way, no one knows. What we do know is that language can never truly be standardized, because it is constantly changing. Soon enough our English language could be a combination of LOLs and LYLASs in order to communicate!

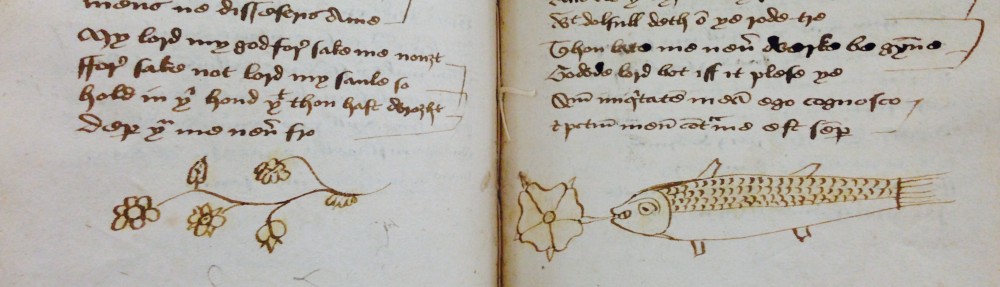

I came across this Buzzfeed article this afternoon and it made me giggle. I thought I would post it just because we have recently been discussing images in manuscripts and how they have meaning that goes with the text it is paired with in most cases. This article is looking at manuscripts and their images and trying to show that this is what life was like in the Medieval time period. I realize that most of these images are not accurate to what the author of the article is trying to portray them as, but they made me laugh and it really intrigued me on what these images really were trying to portray! Seems like whatever it is is a pretty interesting manuscript, I wish I knew what it was!

http://www.buzzfeed.com/donnad/insane-book-about-life-in-the-middle-ages#.ptMYwXNZ9

I found such a fantastic section in today’s reading of OUMEM, on page 44. It says: “Now, paleological dating is not an exact science: one can be fooled by, for instance, an older scribe who has not kept up to date with changes in script, or a young scribe trained by an older one in some remote area, or a scribe who is simply albeit awkwardly imitating an older hand.”

The principle that really grabbed me here is that writers (primary media of their day) represent a huge range of experiences and situations. One of the worst things we can do when we look at a text is to say “This is the way writing was done during ___ time period” or “This is how people thought back then.” While it does represent at least someone, applying these impressions to an entire culture impedes us from a fuller understanding of its people. I loved the idea that in some places certain literary traditions lasted longer than in others, the idea that the world at this time was full of a huge variety of people doing things in all sorts of different ways.

I thought about putting this up as my regular blog post, but I wanted a little more freedom to voice my personal opinion. I often find myself annoyed at the arrogance experts, especially when it comes to history, science, and religion. When something is presented to me as a concrete fact with no room for alternative explanations, I am skeptical. In my mind there is always room for more to any given story or fact. That’s not to say I don’t find these areas useful, or that they do not offer valuable insights to us, it’s just that I haven’t found life to consist of definite explanations. Take our views of “winning” a war, for example. If one side makes another side return home, or wipes out an enemy, we say that side “won.” But the people involved may not experience any sense of accomplishment or even benefited from this victory. Did the people who died fighting for the winning side win? Did their families? What if they didn’t even believe in the cause they fought for?

What I’m getting at here is that there is a whole approach to research that wants to slap labels on everything, and that can really lead to some misinformation. Going back to the OUMEM quote, we can see the potential for misunderstanding the time period in which something was written. A researcher could very easily look at something written by “an older scribe who has not kept up to date with changes in script” and date it much earlier than it really was. Why is this important? Off the top of my head I can think of several reasons:

- The idea that all writing of a time period held to the same conventions distances us from the diversity present during that time. It bars us from a closer shared experience with the text and its original readers.

- Further study could reveal motives for continuing certain literary traditions, such as an affinity for (or repulsion to) change or another language.

- The more quickly we come to a judgment about a text, the less time we spend with it and the less we can learn from it.

According to Wikipedia (how meta, here on our class wiki!), a hive mind can refer to the following (among others):

Collective consciousness or collective intelligence…

…A collective of knowledge, art, artifacts, symbols and social ritual…

Swarm intelligence, the collective behaviour of decentralized, self-organized systems, natural or artificial…

Group mind (science fiction), a type of collective consciousness

Make your contributions to the class hive mind here! Make observations, ask questions, offer answers, post readings of Middle English, link to cool medieval manuscripts (or other books) you’ve discovered—anything that doesn’t really suit a more formal blog post and isn’t totally directly relevant for classroom discussion.

Add new categories! Make this space work for you!