This poem includes much more fighting and war than any other poem we’ve read this semester.

Do you think this is a poem about wars? If so, how do the women figure into these wars?

This poem includes much more fighting and war than any other poem we’ve read this semester.

Do you think this is a poem about wars? If so, how do the women figure into these wars?

First, don’t be confused if you have a memory of Marie de France’s Lanval: this Middle English romance is a version of that story (from a couple of centuries earlier), though as we’ll discuss in class, with some significant differences. But then, you knew most of that from reading the introduction to the poem. Today’s blog question:

What, throughout the poem, accounts for Launfal’s success? What accounts for his losses, his failures?

While studying for the midterm, I was re-reading the notes from last week on the way that manuscripts go through rolling revisions. The idea of this really intrigues me because now a days, authors are very hesitant to share their ideas and more importantly, the credit for their work with anybody. If a book is being published, it is very rare to see more than two author names on the cover. Its just the way that culture has become, people do not like sharing especially when it comes to fame. This idea is partly why the concept of a rolling revision and social authorship is crazy to me. Authors of these manuscripts wrote these manuscripts without any want of fame and fortune. They knew going into the manuscript that others were going to take their work and re-write it, make changes, make edits, and in some cases, just turn it into their own work.

I look up to these authors and scribes. This shows that these people were not interested in the glory of the final product, but they genuinely wanted their stories to be shared and read. In most cases, when a manuscript was being re-written by a different scribe this meant that the manuscript was getting a longer lasting life. This to them was way more important than getting fame for maybe a year and then being forgotten. To me, this really put into perspective the way times have changed since the middle ages. Priorities have changed drastically, and maybe this isn’t such a good thing. Rolling revision may not allow one person to get all of the credit, but it would allow the work to get better and be epitomized over years and years to come. Just think about how much more amazing literature would be if this was still the way things were written.

When reading texts like Piers Plowman and Sir Gawain and the Green Night in their original language, I can’t help but get frustrated when trying to decipher what the modern English word would be. It honestly amazes me how much English has changed over time. The differences between Old English and modern English are so diverse that it is hard to believe that they are the same language.

I took English 309 (English Language-Grammar and History) last semester, and thank God I did, because it really helped me learn the Old English alphabet. However, it makes me wonder what our English language will become in the next 100 years. If English changes so much from 1300 to now, how different will it be in 2116. Will English consist of abbreviations? Will English engulf another language like it did with French and Latin?

As humans, we innately choose the easiest and most efficient way of doing something. The same is true for language. According to the Ease of Articulation Principle, humanity always finds a way to change the sound of a word in a way that is easier to pronounce. This is why Old English and Modern English are so aesthetically different. Why Old English started out in such a complicated way, no one knows. What we do know is that language can never truly be standardized, because it is constantly changing. Soon enough our English language could be a combination of LOLs and LYLASs in order to communicate!

This semester I am also taking the Walt Whitman Seminar class, and one of the things that we’ve discussed is Whitman’s additions and revisions to Leaves of Grass. He released several editions of the text throughout his lifetime, adding in new work each time. Each new work was a response the changing world and ideologies around Whitman and in America. In this way, Whitman’s work was able to maintain a sense of relevancy and timeliness (though he rarely cites specific worldly events or things in his work). I really like his philosophy when it comes to revision; one of the theories that I’ve drawn from his work is that humanity is in constant revision. We will never reach a point of perfection because there is a consistency to progression and regression based on the cyclical nature of life. By being faced with struggles and regressions he’d encountered before, Whitman believed it to be a way to formulate a more clear identity of ourselves. We can’t not be who we were yesterday, and thus our identity comes from a formulation of who we were yesterday in conjunction with who we are today. Together, these two separate moments create a pathway for what our future will be.

I really like this philosophy in the context of Piers Plowman, which was also revised several times throughout its life as a manuscript. Each new revision was a response to the changing world and ideologies surrounding the manuscript. For example, the C manuscript (before 1385) is responsive to the Peasants Revolt. The text was able to survive and maintain a relevancy in Medieval culture because like Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, it was responsive and timely. I think the copious amounts of different manuscripts and its long, active life during its time speaks to the necessity of revision overall. For the necessary advancement of culture and ideology, it is wise and at some points necessary to look back and revise what has already existed. By evaluating who we were and who we are now are necessary to create a new pathway for the future.

Now that we’re at the end of Chapter 1, we have learned about the different styles and quirks that ultimately make a scribe as well as the close-knit niche literary circles to which he/she belonged. Each author and scribe is mysterious in his/her own right to modern scholars, but I found it particularly interesting that Kerby-Fulton includes in the text some fairly well-known aspects of some of the major poets’ work that remind us of the modern fiction writing culture we experience in the modern day. We may not need to do any guesswork with books today (because we utilize advanced, digital printing technology and no longer need to copy material by hand), but author/editor purposes remain unchanged. In Piers Plowman, for example, the person who manually churned out his extremely long text (whether it was a “moonlighting” Langland himself or a hired scribe) was in charge of the codicology of the work: the hand in which it was written and the distinctive, telling traits of the manuscript writing itself. However, the author maintains his “overall tone of indignation” despite scribal control (73). Of course, if Langland was his own scribe, he had all the more power to keep his intentions intact. Chaucer is a prime example of scribal power vs. authorial intention; his unfinished Canterbury Tales were “ravaged by scribal intervention” and were likely subject to what Kerby-Fulton refers to as “rolling revision” (74-5), or continual editing. Chaucer’s poetry even directly criticizes his scribe Adam Pinkhurst/Scribe B as a rapist of sorts – one who has too much power to change and permanently mess up the original author’s work. In the end, though, I perceived both Chaucer and Langland as effective authors due to their unique, even radical tones. In the ever-hilarious Miller’s Tale, Chaucer’s “insistent use of ‘hende’ [is] as overt to medieval readers as it is to us” (85). If you’ve ever read this story, you know that it is what we have come to know as quintessentially Chaucerian in working class subject matter and playful tone. Nicholas is young, cunning, and sexually forward with Alisoun, his equally vulgar female partner; hence his description as “hende”/”handy.” It makes one wonder, though, how much of it is Chaucer’s own voice.

On page 78 in our reading for today begins a section entitled “Professional Scribes, Commercial Scribes, and Booklet Production.” Here the authors make the distinction between the “professional”–a scribe who works in some sort of legal or bureaucratic capacity, and the “commercial”–a scribe who is paid to produce works for others. The interesting relationship between the professional and commercial scribe, according to the authors, is that they are often the same person. It is fascinating to consider that the same scribes who would work all day in a courtly or legal setting would then go home (or elsewhere) to moonlight. This concept brings about two associations in my mind: one, that the scribes loved the art of manuscript production so much that they would willingly do continue the process in their free time, and two, that scribes simply used their skills for supplementary income. Both ideas add a very humanizing element to a group of people who often seem distant and unknown. The image of some medieval scribe working on a commissioned piece in his home after work brings about all sorts of questions. Did most scribes have the necessary materials to work outside of their places of employment? Where those places even separate from their home? How well known were individual scribes, and what was the process for requesting a commission? What was the quality of life for an average scribe (did they hold any sort of celebrity status)?

On this website,

Making Books for Profit in Medieval Times

which looks eerily familiar, I found a quote from an unnamed scribe saying, “For so little money I never want to produce a book ever again!” I wonder if this sort of sentiment was commonly felt by other scribes of the period.

In Chapter one of Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts, the author goes into detail about the different variations that have been made of the Canterbury Tales. Many things stood out to me about this. For instance, the fact that not a lot is known about the original compilation of the tales and why Chaucer did not finish his tales. I thought it was really interesting to see a side by side comparison of the HG and the EL manuscripts and how the scribes decided to order the tales. Many of the tales stay in the same place in both manuscripts, but then some of the tales such as “Man of Law’s Tale” are in completely different places. Did the different scribes find different meaning in this tale? And if so, why did they choose to put it where they did?

Another major mystery that goes along with the Canterbury Tales is the mysterious ending of the tales. The author of OEMUM goes into detail about how each scribe handled the ending of “The Cook’s Tale”. The two manuscripts that the author looked into, HG and EL, both did not try to cover up the ending up the cook’s tale by adding information on Gamelyn, but some of the other manuscripts that were written in this time period did. I thought this was incredible that some scribes actually decided to change the work of Chaucer by adding a complete new ending to the story. Some of the scribes supposedly did this in order to make the story more finished and, supposedly, better. In my opinion, I think leaving Chaucer’s original work is much more satisfying, even if it is not finished.

I was amazed to read about all of the unknown things that surround the Canterbury Tales. As one of the most iconic works in literary history, you would think that they would know much more about it. It was very interesting to me to read about all of the different theories surrounding the manuscripts and all of the scribes. The fact that something with such little information on it is so iconic, even centuries later, just makes the Canterbury Tales even more intriguing to me!

In Chapter 1 of Opening Up Middle English Manuscripts, we go into detailed study surrounding the content and reproduction of Piers Plowman from scribe to scribe. In viewing these various manuscripts, the question is posed as to whether metrical changes are made by William Langland or Scribe D. It’s possible that the manuscripts in question were actually drafts written by Langland, as our texts says possibly drafted “without alliteration… then worked them up” (OUMEM 73).

If this is true, William Langland’s case study would have some curious implications for the creative writing process of the late fourteenth century. For one thing, it would mean that at least Langland was more preoccupied with the story he was telling than the poem’s metrical effects. Were Langland and other authors trapped in the popular genre of their era? Surely the intellectual community of Britain during this time was exposed to non-rhyming prose, whether it was verbal story telling or copies of ancient Greek prose. Of course, we do not have enough information to comment on the intentions behind Langland’s writing process, because he may have always intended for poetry to carry the final product. However, the question is worth asking considering the content of his poem; a clear message is being sent about the church as a corrupt governing body, so it would be interesting to see if poetry was the necessary medium for reaching a wider audience, while the content carries the weight.

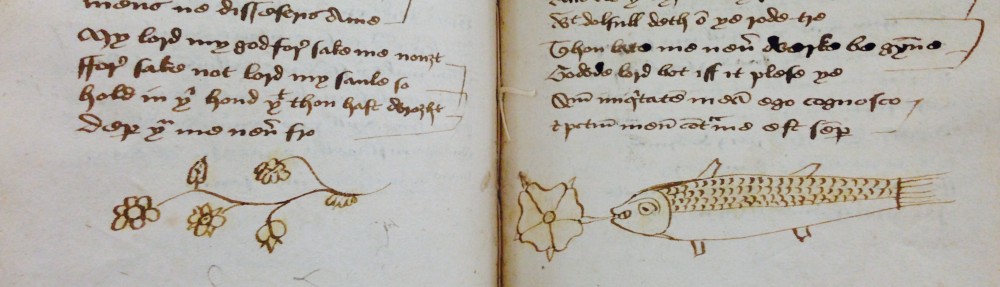

A few classes ago we talked about the debate over images in manuscripts. I think it’s interesting how in today’s society we almost get annoyed or uninterested if there aren’t images to go along with the text. Advertisements, magazines, and newspapers without images fail to capture our attention. When it comes to images in the realm of advertising, people are hired and paid huge sums of money to specifically read audiences in order to understand what audiences find most interesting and attention catching. It is crazy to think that in the times of the medieval manuscripts we are studying that images were almost taboo. In the end, obviously images were permitted but only on the grounds that they helped the illiterate understand the text and they helped drive further the meaning of the text. However, I found an “article” that highlights some odd and interesting images in medieval manuscripts that seem to stand in opposition to necessary images. Although I’m not sure how accurate they are, I do find them highly entertaining.

http://www.buzzfeed.com/babymantis/20-bizarre-examples-of-medieval-marginalia-1opu