Michael David Cohen

USC’s First Desegregation, 140 Years Ago

Last month, the University of South Carolina commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of desegregation at that institution. The three African Americans who enrolled there in September 1963 were the first to do so in the twentieth century. Yet they were not the first ever. This month we reach the anniversary of an earlier desegregation attempt at USC. One hundred forty years ago, on October 10, 1873, a state transformed by the Civil War opened its university to former slaves.

Before the Civil War, South Carolina College, as it was known, educated the South’s white male elite. Planters sent their sons to Columbia to study the classical languages and mathematics, knowledge they deemed essential for the region’s economic and political leaders, and to develop relationships with other young members of their class. White women studied at separate women’s colleges. African Americans, nearly all of them enslaved, received no formal education. State law, in fact, made it a crime to teach a black person to read.

The war interrupted the university’s work. Nearly all students had enlisted in the Confederate military by mid-1863; that summer, the army took over the campus as a hospital. When the school reopened in January 1866, now renamed the University of South Carolina and reorganized into eight schools teaching liberal and professional subjects, most of its students were Confederate veterans. All, as before, were white men.

But change was brewing. Reconstruction soon came to South Carolina. Emancipated and enfranchised blacks, now the majority of the state’s voters, in 1868 elected a Republican and black majority to the state legislature. These lawmakers tried to use their new power to bring true freedom and equality to former slaves. They created the Land Commission, for example, to help the poor purchase land. They tried to ban discrimination in public accommodations, though whites in the state senate managed to defeat that bill. And these fights were not happening in the state capitol. Wartime damage had rendered it unusable. Instead, they were meeting in the USC chapel. White students, fearful of the legislators’ efforts, sat in the gallery watching their state get remade.

Soon the Republican politicians turned their attention to the university around them. The legislature passed and, on March 3, 1869, the governor signed a law banning racial discrimination in admission. That was a key legal step. But it had no immediate result. The trustees and the professors, many of them holdovers from the antebellum college, made no evident effort to recruit African Americans. Four years after the law, not one had enrolled.

In fall 1873, the legislature tried again to spark change: it appointed a black majority to the board of trustees. Now the university began responding. The medical school, created after the war and less mired in antebellum tradition than USC’s other units, acted first. It enrolled Henry Hayne, South Carolina’s African American secretary of state, in its program. Hayne became USC’s first black student. His admission aroused anger both outside and within the university; four professors immediately resigned. But the trustees defended the medical school’s decision—and took it further.

On October 10, 1873, the trustees defended Hayne as “a gentleman of irreproachable character, against whom the said Professors can suggest no objection except . . . his race.” “This board cannot regret,” they continued, “that a spirit so hostile to the welfare of the State, as well as to the dictates of justice and the claims of our common humanity,” had left USC with the four professors’ resignations. The university, they declared, “is the common property of all our citizens without distinction of race.” (Minutes of the Board of Trustees, University of South Carolina Archives)

This declaration, published in the local newspaper, transformed the university. It had, until recently, been a cultural training ground for white slaveholders. Now the trustees wanted it to bring educational opportunities to former slaves.

The trustees understood that, if they wanted blacks to study at the university, an administrative fiat was not enough. People only a dozen years out of slavery had neither the educational background nor the money needed for a traditional college education. The trustees tried to overcome both impediments. To educate ill-prepared students, they created a preparatory school—a high school—within USC. To accommodate poor youths, they eliminated tuition and made dormitory housing free. A new scholarship program even awarded monthly stipends to those students who performed best on a written test; in 1874–75 the state spent over eleven thousand dollars on fifty-seven scholarships.

Reforms in admission were not limited to race. Anxious to train teachers for South Carolina’s expanding primary and secondary schools, the legislature created a normal school—a teacher-training institute—on the Columbia campus. Unlike the rest of the university, the normal school admitted women. For the first time, USC was open to blacks, to the poor, and to women. Its leaders were trying to make the public university truly a university of the people.

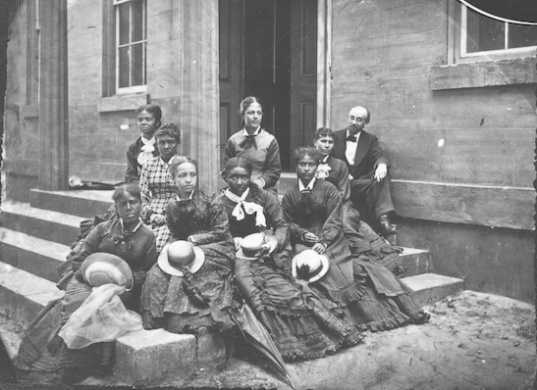

(Students of the State Normal School at the University of South Carolina, c. 1875. None of the students are identified. The man on the right may be Mortimer A. Warren, principal of the normal school—uncertain, but likely. Photograph used with permission of University of South Carolina Archives.)

They succeeded. Many poor black men enrolled, often beginning in the preparatory department before advancing to the university proper. Only seven African Americans entered the classical collegiate program the first year, but the next year the freshman class blossomed to twenty-nine. Black women enrolled in the normal school. Some black alumni later used their education to begin prominent careers. George Murray, for example, became a teacher, author, and congressman. James Durham became a physician and secretary of the South Carolina Baptist Convention.

As blacks came, whites left. Few of South Carolina’s white men were willing to study alongside blacks. Those who did stay, clearly a pro-Reconstruction lot, got along well with their new classmates. White and black students did not share rooms, but they did study and socialize together. Meanwhile, another professor left and the trustees fired three more—presumably owing to their attitude toward or treatment of black students. The trustees replaced one of them with Richard Greener, Harvard’s first black graduate and now USC’s first black faculty member. Reconstruction had brought African Americans to the university as trustees, students, and faculty.

Of course, this story did not end happily. A second desegregation was needed at USC because the first one had failed. In 1876–77, aided by massive election fraud, white Democrats won back control of South Carolina’s government. Calling themselves “Redeemers,” these politicians rolled back the Reconstruction reforms. They closed the state university, then reopened it in 1880 as the South Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanics—an all-white institution. Furthermore, because the normal school did not reopen, the new college was also all male. No more women enrolled until 1893; no more blacks, until 1963.

The Redeemers, though, did not undo every Reconstruction innovation. They restored the university’s all-white and all-male student population, but they did not restore tuition. Black Republicans had made USC free to promote the education of former slaves. White Democrats kept it nearly free—students now paid a ten-dollar matriculation fee and the cost of room as well as board—to enable poor whites to attend. Ironically, then, Reconstruction’s legacy at the University of South Carolina was the expansion of access to more white men. Expanding it beyond them would take another civil rights movement.

Michael David Cohen, assistant research professor of history at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, is author of Reconstructing the Campus: Higher Education and the American Civil War and coeditor, with Tom Chaffin, of the newly released Correspondence of James K. Polk, volume 12, January–July 1847.

Filed under: Jubilee Project

![]()