Citizen Kane’s 100% Positive Status on Rotten Tomatoes ruined…by an 80 Year-Old Review

You may have seeing this story going around online. Rotten Tomatoes aggregates movie reviews (with what it calls its “Tomatometer”) and scores titles accordingly. For who knows how long, Orson Welles’s debut as a Hollywood director, the widely lauded (and widely taught) Citizen Kane (1941) has enjoyed a perfect score of 100%. That is, until someone posted a not-so-enthusiastic review that was published in the Chicago Tribune in 1941. The reviewer, going by the a-bit-too-cute pseudonym Mae Tinee, praised Welles’s acting, but said “meh” about everything else. The lighting was depressing (“I kept wishing they’d let a little sunshine in”), even a little creepy. On the whole, writes Mae Tinee, the film lacks “general entertainment value.”

Chirarscuro lighting in Citizen Kane, designed, very likely, by cinematographer Gregg Toland, in collaboration with Welles

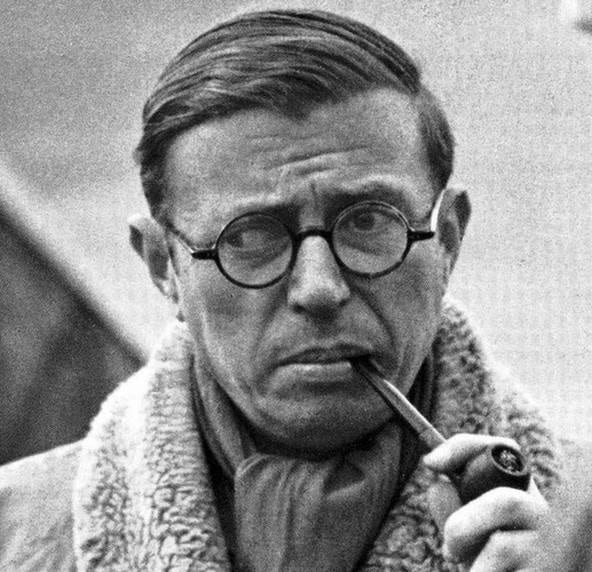

This is actually not the first bad review of Citizen Kane to have an impact on the film’s reputation. French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre had seen the film during a visit to New York City. Upon his return to Paris, he presented his opinion in the pages of the journal L’Ecran Français under the title “Quand Hollywood veut faire penser…Citizen Kane d’Orson Welles” (“When Hollywood Wants to Make Us Think…Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane). Wrote Sartre: “Kane might have been interesting for the Americans, [but] it is completely passé for us, because the whole film is based on a misconception of what cinema is all about. The film is in the past tense, whereas we all know that cinema has got to be in the present tense. ‘I am the man who is kissing, I am the girl who is being kissed, I am the Indian who is being pursued, I am the man pursuing the Indian.’ And film in the past tense is the antithesis of cinema. Therefore Citizen Kane is not cinema.”

When Sartre published his review in 1945, Citizen Kane had not yet been screened in Paris, because during WWII, occupying Germany had banned Hollywood films. So when it finally premiered in Paris in the summer of 1946, professional critics naturally sided with Sartre. Citizen Kane didn’t stand a chance.

Jean-Paul Sartre

It wasn’t until French film critic André Bazin began showing Citizen Kane in ciné clubs throughout Paris, following each screening with a passionate defense of the film (in particular, its use of deep focus photography–a technique in which objects in the foreground, middle ground, and background are equally in focus), that people began to open their eyes (and minds) and realize what an extraordinary achievement Kane is.

In an essay entitled “The Technique of Citizen Kane,” published in 1947 in the journal Les Temps Modernes, an exasperated Bazin writes: “Well, then, let’s talk once more about Citizen Kane. Today, as the last echoes from the critics seem to have faded away, we can take stock of their judgments.” He then went on to respond, one by one, to each point Kane‘s detractors had leveled, and he eviscerated them all. In regards to the criticism that Welles’s use of deep-focus photography was nothing new, that Keaton used it long before Welles did, Bazin reminded his readers that Keaton filmed outdoors. Kane, however, was shot on a sound stage at the RKO studio lot, which was not conducive to shooting in depth–it required special lighting, extra high speed film, and the wide angle lens of the new Mitchell BNC motion picture camera, which few in Hollywood, besides Toland, had any interest in using.

Toland (left) and Welles (right) on the set of Citizen Kane

Thanks to Bazin’s tireless efforts, the reputation of Citizen Kane–and Orson Welles–soared among critics and moviegoers. In France, at least. It would take another couple of decades before Kane was appreciated in the United States. Upon its initial release, RKO did little to promote the film, fearing backlash from the powerful newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, upon whom the tragically flawed character of Charles Foster Kane was modeled. The film went into relative obscurity.

But by the late 1960s and early 1970s, Citizen Kane began to emerge from obscurity, thanks in part to American film critic Andrew Sarris, who brought French film criticism into vogue. Kane was especially popular among college students, as the film was screened on campuses across the country. Its cult status was not lost on cartoonist Charles Schultz, who devoted a number of panels to the film. In the September 12, 1971 Sunday strip, Snoopy, posing as the hipster “Joe Cool,” stops by a student union bulletin board to check out the campus events and sees an ad for a screening of Citizen Kane (“I’ve only seen it twenty-three times,” he says to himself).

Snoopy as “Joe Cool” in Charles Schultz’s “Peanuts”

Today, Citizen Kane is no longer just a French thing (like Jerry lewis or Mickey Rourke), nor is it a cult favorite (like, say, Welles’s other masterpiece, the 1958 noir-thriller Touch of Evil). It is rightly recognized as a landmark achievement in movie history–“a dialectical leap forward in the evolution of the language of cinema,” as Bazin put it. Only Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 romance-thriller Vertigo is regarded more highly than Kane. It stole the #1 spot from Kane in the BFI’s 2012 list of the 100 Greatest Films of All Time (the next BFI list is due in 2022–we’ll see if Kane stays at #2).

One wonders if the true identity of that lone Rotten Tomatoes reviewer will ever be revealed. Who knows? Maybe Mae Tinee was none other than…Jean-Paul Sartre.