by: Zoee Reale

As a general fan/ admirer of Chris Cornell’s lyrical work—whether it was his songs for Soundgarden, Temple of the Dog, Audioslave, or even his solo stuff, I’ve always found this subtle gothic undertone that comes with the subject matter that Cornell writes about. And many can argue that his impressive vocal range was a key to this sound, I think there are some gothic themes at play in his writing.

I would like to examine the lyrics of Audioslave’s debut album and discuss some of the gothic links that can be found in a majority of these songs. I want to begin by pointing out some of the obvious gothic literature references and then work down to the not-so-obvious—which more-or-less correlate with gothic thematics that are found inside of the genre. I’ll discuss some of the songs’ music videos that may further highlight these explored themes. It is important to note here that a majority of this is my initial interpretation of the lyrics based on some of the gothic texts I’ve previously studied.

Much of the album’s subject matter was largely speculated by fans to revolve around Cornell’s struggle with drug use and recovery. While I can agree with this sentiment, I would also like to speculate on the themes of death/rebirth, hauntings/ the supernatural, psychological torment, faith, and the past.

To point out the most obvious of gothic references would be found in Track 2; “Show Me How To Live”. It depicts a retelling of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein;

And with the early dawn

Moving right along

I couldn’t buy an eyeful of sleep

And in the aching night under satellites

I was not received

Built with stolen parts, a telephone in my heart

Someone get me a priest

To put my mind to bed

This ringing in my head

Is this a cure or is this a disease?

Even though the first verse opens with an obvious connection to Dr. Frankenstein’s madness in trying to create the daemon, a lot of listeners began misinterpreting the song for religious references with the chorus;

Nail in my head from my creator

You gave me life, now show me how to live

The religious reference was mistaking the word “head” for “hand” to depict Jesus being nailed on the cross. Cornell debunked this confusion on Twitter a few years later, by responding to one person by simply saying “Frankenstein”.

Track 9, Exploder depicts a series of eerie fates. There are a lot of gothic themes of violence, and psychological anguish; telling of a man who was wrongfully accused and forever imprisoned, a girl who takes her life just as her father did, and a boy who kills his mother based on the voices in his head. The most interesting gothic connection I want to point out is a seemingly subtle reference to Edgar Allan Poe’s story “William Wilson” in the last verse;

There was a man who had a face that looked a lot like me

I saw him in the mirror and fought him in the street

Then when he turned away, I shot him in the head

Then I came to realize, I had killed myself

While I cannot find a direct comment that this verse is a “William Wilson” reference, it definitely feels close to the ending of Poe’s story;

“Not a thread in all his raiment–not a line in all the marked and singular lineaments of his face which was not, even in the most absolute identity, mine own! … ‘–and , in my death, see by this image, which is thine own, how utterly thou hast murdered thyself’”

Personally, I find this song to be one of the more darker laden songs on the album as it does contain these troubling occurrences that don’t have a great resolution–not that all of Cornell’s songs have a great resolution, a large portion of his songs do tend to remind me of these Poe-esqe endings where someone is left to their own devices in madness and speculation.

Possibly one of the best-known songs of Audioslave is their fifth track, “Like a Stone”. The song seems to be playing with themes of death and a connected struggle with religion by placing the Narrator inside an empty house, waiting for whatever comes next.

On a cobweb afternoon in a room full of emptiness

By a freeway, I confess I was lost in the pages

Of a book full of death, reading how we’ll die alone

And if we’re good, we’ll lay to rest anywhere we want to go

A lot of Cornell’s lyrics remind me of a strange melody of Poe and Emily Dickinson, especially when involving this vast emptiness and speculation about death. More focusing on the resembled themes Dickinson uses, I could pick out several of her poems that feel reminiscent of Cornell’s song (Here I’ll use the first and last stanza of Dickinson’s poem #279)

Tie the Strings to my Life, My Lord,

Then, I am ready to go!

Just a look at the Horses–

Rapid! That will do!

…

Goodbye to the Life I used to live–

And the World I used to know–

And kiss the Hills, for me, just once–

Then–I am ready to go!

For some final thoughts, I will say that a large majority of this album brings the listener to decipher Cornell’s howls and yells to truly get down to what the lyrics are saying. At the core, I find that there is typically a singular character, left to his own thoughts and troubles trying to escape the trials he is in; decidedly that be life, the afterlife, or himself. It is interesting to pick apart this progression of gothic imagery and potential references, which gives me an even better appreciation of Cornell’s genius in his work.

For some final thoughts, I will say that a large majority of this album brings the listener to decipher Cornell’s howls and yells to truly get down to what the lyrics are saying. At the core, I find that there is typically a singular character, left to his own thoughts and troubles trying to escape the trials he is in; decidedly that be life, the afterlife, or himself. It is interesting to pick apart this progression of gothic imagery and potential references, which gives me an even better appreciation of Cornell’s genius in his work.

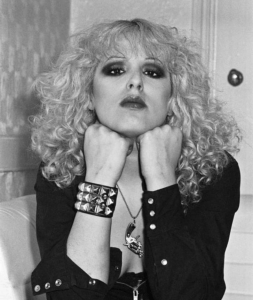

Their relationship had an addictive quality for the two of them and the public. Nancy and Sid brought out the

Their relationship had an addictive quality for the two of them and the public. Nancy and Sid brought out the  self-destruction, and Nancy’s enablement of those behaviors, “for a chemical imbalance, you sure know how to ride a train” (0:18-0:26). When asked to explain this lyric Bridgers tweeted, “even though you have no personality other than your drug addiction you are hot and cool”. Nancy’s perception of Sid was a ticket to fame, drugs, and fun along the way. In articles about her life, it was stated Nancy would have ended up with a rock star if it was Vicious or not as she craved their dizzying lifestyle. Nancy met Sid because she was the Sex Pistol’s dealer, and their growing fame did nothing but draw her closer to the band. Even after Nancy’s death, Sid cannot break away from the relationship they cultivated, “There is no distraction that can make me disappear / No, there’s nothin’ that won’t remind you I will always be right here” (1:09-1:25). Both chilling and tender, this line sports a double meaning of haunting and reassurance. Once again, Spudgen and Vicious’ relationship is suspended by an inevitable, immature death, continued by Nancy’s ghost.

self-destruction, and Nancy’s enablement of those behaviors, “for a chemical imbalance, you sure know how to ride a train” (0:18-0:26). When asked to explain this lyric Bridgers tweeted, “even though you have no personality other than your drug addiction you are hot and cool”. Nancy’s perception of Sid was a ticket to fame, drugs, and fun along the way. In articles about her life, it was stated Nancy would have ended up with a rock star if it was Vicious or not as she craved their dizzying lifestyle. Nancy met Sid because she was the Sex Pistol’s dealer, and their growing fame did nothing but draw her closer to the band. Even after Nancy’s death, Sid cannot break away from the relationship they cultivated, “There is no distraction that can make me disappear / No, there’s nothin’ that won’t remind you I will always be right here” (1:09-1:25). Both chilling and tender, this line sports a double meaning of haunting and reassurance. Once again, Spudgen and Vicious’ relationship is suspended by an inevitable, immature death, continued by Nancy’s ghost.

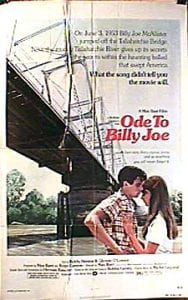

There have been a few other recordings of “Ode to Billie Joe,” but it’s one of those records where the original performance is so crucial to the song’s effect that it’s almost impossible to cover. Remaking it is sort of like remaking Psycho — it can be done, but why? It’s a perfect recording, sad and creepy and as Gothic as anything we’ve studied this semester.

There have been a few other recordings of “Ode to Billie Joe,” but it’s one of those records where the original performance is so crucial to the song’s effect that it’s almost impossible to cover. Remaking it is sort of like remaking Psycho — it can be done, but why? It’s a perfect recording, sad and creepy and as Gothic as anything we’ve studied this semester.