–Adapted from Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work by Susan Farrell. ((New York: Facts on File Press, 2008).

Kurt Vonnegut was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on November 11, 1922, the third child of  Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. and Edith Lieber Vonnegut. Both Vonnegut’s father, Kurt Sr., and his grandfather, Bernard Vonnegut, were local architects in Indianapolis. While the family was comfortably well-to-do during Vonnegut’s earliest childhood, they suffered financial setbacks during the depression years. As a result, Vonnegut attended public schools even though his older siblings had received private school educations. But Vonnegut thrived at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, where he played clarinet in the school band and served as a writer and editor fo

Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. and Edith Lieber Vonnegut. Both Vonnegut’s father, Kurt Sr., and his grandfather, Bernard Vonnegut, were local architects in Indianapolis. While the family was comfortably well-to-do during Vonnegut’s earliest childhood, they suffered financial setbacks during the depression years. As a result, Vonnegut attended public schools even though his older siblings had received private school educations. But Vonnegut thrived at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, where he played clarinet in the school band and served as a writer and editor fo r the school’s daily newspaper.

r the school’s daily newspaper.

After graduating from high school in 1940, Vonnegut enrolled at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, as a biochemistry major. Despite joining a fraternity, he disliked Cornell and did not feel that he fit in well until he joined the staff of the college newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun, where he found a home. But his grades remained low, and Vonnegut ended up withdrawing from Cornell his junior year after coming down with a severe case of pneumonia.

Having enlisted in the U.S. Army in November of 1942, a few months before he actually left Cornell, Vonnegut was sent to basic training in 1943. During his army training, he studied mechanical engineering at Carnegie Technical Institute and the University of Tennessee. Vonnegut was later stationed at Camp Atturbury, just south of Indianapolis, close enough to home for weekend visits. On one such visit , over Mother’s Day, 1944, Vonnegut’s mother Edith died from an overdose of sleeping pills, a death that Vonnegut always considered a suicide and that would haunt the writer for the rest of his life.

A few months after his mother’s death, Vonnegut’s army unit, the 106th Infantry Division, was shipped overseas to fight in World War Two. Vonnegut, along with the five other battalion scouts in his unit and about fifty other American soldiers, was captured by the German Army in December of 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge, the last main German offensive of the war. Vonnegut and his fellow American prisoners were shipped to Dresden in railroad boxcars, where he worked in a factory that manufactured a vitamin-fortified malt syrup for pregnant women, and where, on the night of February 13, 1945, he experienced the Allied firebombing of the city, events fictionalized as part of Billy Pilgrim’s war experiences in Slaughterhouse-Five.

battalion scouts in his unit and about fifty other American soldiers, was captured by the German Army in December of 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge, the last main German offensive of the war. Vonnegut and his fellow American prisoners were shipped to Dresden in railroad boxcars, where he worked in a factory that manufactured a vitamin-fortified malt syrup for pregnant women, and where, on the night of February 13, 1945, he experienced the Allied firebombing of the city, events fictionalized as part of Billy Pilgrim’s war experiences in Slaughterhouse-Five.

Arriving back home in Indianapolis in May of 1945 as a twenty-two year old war veteran with a Purple Heart, Vonnegut soon married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Cox. In December of 1945, the newlyweds moved to Chicago, where Kurt enrolled in the University of Chicago as a graduate student in Anthropology and Jane, a Swarthmore College graduate, received a full scholarship to undertake graduate studies in Russian, although she never earned her degree, dropping out of school when she became pregnant with the couple’s first child, Mark. During his time as a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Vonnegut also worked as a reporter for the Chicago City News Bureau.

The young family moved to Schenectady, New York in 1947, when Vonnegut was offered a job in the public relations department at General Electric. It was at General Electric that Vonnegut would begin his career as a fiction writer, gathering material for his first short stories as well as his early novels—Player Piano and Cat’s Cradle especially—from his experiences there. Selling several short stories to slick magazines like Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post in the early 1950’s allowed Vonnegut to quit his public relations job, move to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and settle into writing full time. His first novel, Player Piano, about a machine-dominated future, was published by Scribner’s in 1952.

Although Vonnegut continued to earn the majority of his income through his magazine story sales in the decade of the 1950s’s, the pressures of a growing family–son Mark had  been born in May of 1947, daughter Edith in 1949, and daughter Nanette in 1954–caused him to turn his hand to other means of earning money as well. He taught at a school for learning disabled children for a brief period and even operated a Saab auto dealership on Cape Cod. But Vonnegut’s family life took a traumatic turn in 1958, when his sister Alice died of cancer forty-eight hours after her husband, James Carmalt Adams, had been killed in a commuter train crash in New York City. The Vonneguts adopted the three oldest Adams boys, fourteen-year-old James, eleven-year-old Steven, and nine-year-old Kurt, after their parents’ deaths. A much younger brother, Peter, a baby at the time, was eventually adopted by a first cousin of his father, who lived in Birmingham, Alabama.

been born in May of 1947, daughter Edith in 1949, and daughter Nanette in 1954–caused him to turn his hand to other means of earning money as well. He taught at a school for learning disabled children for a brief period and even operated a Saab auto dealership on Cape Cod. But Vonnegut’s family life took a traumatic turn in 1958, when his sister Alice died of cancer forty-eight hours after her husband, James Carmalt Adams, had been killed in a commuter train crash in New York City. The Vonneguts adopted the three oldest Adams boys, fourteen-year-old James, eleven-year-old Steven, and nine-year-old Kurt, after their parents’ deaths. A much younger brother, Peter, a baby at the time, was eventually adopted by a first cousin of his father, who lived in Birmingham, Alabama.

Vonnegut continued to write in the midst of family turmoil, turning back to the form of the novel at the end of the decade, and soon publishing as paperback originals two wildly different novels: Sirens of Titan in 1959 and Mother Night in 1962. Although Vonnegut was now established as a published writer, sales of his books were small and he remained largely unknown. When his paperback editor, Samuel Stewart, of the Western Printing Company, moved to Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, he arranged for Vonnegut’s next novel, Cat’s Cradle (1963), to come out in hardback. The novel, an apocalyptic tale of destruction caused by the invention of the fantastical weapon ice-nine, a thinly veiled metaphor for the atomic bomb, was critically well-received in key places. While Cat’s Cradle hardly made Vonnegut a household name, it did increase the small but devoted fan base the author had earned from his previous novels. Cat’s Cradle was particularly popular among college students, earning Vonnegut something of a cult following on college campuses, where students often introduced the author’s work to their professors.

Another turning point in Vonnegut’s career came in 1965, when he accepted a two-year teaching position at the prestigious Iowa Writer’s Workshop. In Iowa, Vonnegut was able,  for the first time, to immerse himself in a community of creative writers, both students and fellow faculty members. His fifth novel, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, the story of a tender-hearted but hapless millionaire who hopes to create a better world by being intensely sympathetic to all of his fellow human beings, was published by Holt, Rinehart & Winston in 1965. But it was his masterpiece, Slaughterhouse-Five, published in 1969, that made Vonnegut a wealthy man as well as a celebrity. The novel tells the tale of preposterous soldier Billy Pilgrim, a tall, ungainly chaplain’s assistant

for the first time, to immerse himself in a community of creative writers, both students and fellow faculty members. His fifth novel, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, the story of a tender-hearted but hapless millionaire who hopes to create a better world by being intensely sympathetic to all of his fellow human beings, was published by Holt, Rinehart & Winston in 1965. But it was his masterpiece, Slaughterhouse-Five, published in 1969, that made Vonnegut a wealthy man as well as a celebrity. The novel tells the tale of preposterous soldier Billy Pilgrim, a tall, ungainly chaplain’s assistant  from Ilium, New York, who is captured by Germans during World War Two and survives the Dresden bombing in a concrete slaughterhouse. Back in Ilium as a middle-aged optometrist, Billy is kidnapped by space aliens who take him to the planet Tralfamadore to be mated with an American porn star. Billy’s war experiences, however, have left him “unstuck in time” so that he travels back and forth between his Tralfamadorian experiences, his war memories, and his time in Ilium, unable to control where he will go next.

from Ilium, New York, who is captured by Germans during World War Two and survives the Dresden bombing in a concrete slaughterhouse. Back in Ilium as a middle-aged optometrist, Billy is kidnapped by space aliens who take him to the planet Tralfamadore to be mated with an American porn star. Billy’s war experiences, however, have left him “unstuck in time” so that he travels back and forth between his Tralfamadorian experiences, his war memories, and his time in Ilium, unable to control where he will go next.

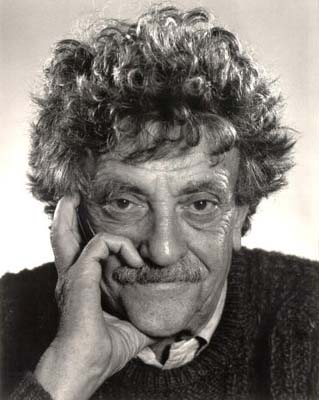

Vonnegut maintained a high profile after the publication of Slaughterhouse-Five, speaking frequently at colleges and universities, writing articles and book reviews, dabbling again in journalism, and even trying his hand at play writing. At the same time his professional career was blossoming, however, Vonnegut’s personal life was very much in flux. He separated from his wife, Jane Cox Vonnegut, in 1971, and moved from Cape Cod to Manhattan, where he began living with photographer Jill Krementz, who would become his second wife in 1979, after he and Jane were officially divorced. Despite a tumultuous personal life, Vonnegut would go on to publish three more novels in the decade of the 1970’s as well as his first collection of speeches and essays, Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons.

Remaining prolific over the 1980’s and 1990’s, Vonnegut published a children’s book, Sun Moon Star (1980), with illustrations by graphic artist Ivan Chermayeff, two more books of collected speeches, essays, and anecdotes which he characterized as “autobiographical collages,” as well as five more novels. Although artistically productive during this period, Vonnegut was also battling severe depression. In the mid-80’s, like his mother before him, Vonnegut attempted suicide by ingesting a combination of sleeping pills and alcohol. After his recovery, he would write and speak frankly about the mental problems affecting his mother and son Mark, and about his own depression, especially in the autobiographical work Fates Worse Than Death (1991).

In early 2000, Vonnegut was nearly killed in a small home fire in his Manhattan brownstone, a fire which appeared to be the result of the writer’s carelessness in smoking his famous unfiltered Pall Mall cigarettes. Rescued by a neighbor and by his and Jill’s adopted teenage daughter Lily, Vonnegut spent several days in the hospital in critical condition suffering from smoke inhalation. He eventually made a complete recovery, and went on to publish, in 2005, at the age of eighty-two, another collected volume of speeches, anecdotes, and opinions, called A Man Without a Country. The book particularly emphasizes Vonnegut’s disappointment with the presidential administration of George W. Bush, and Bush’s leading of the country into war with Iraq. In publicity appearances to support this book, Vonnegut re-cemented his earlier connection to young people, even appearing on The Daily Show, the immensely popular satirical news program hosted by comedian Jon Stewart.

At the very end of his life, Vonnegut turned largely from writing to the visual arts. In a brief Author’s Note at the end of A Man Without a Country, Vonnegut explains that the  illustrations which appear in the book are the result of a relationship he had developed with a Kentucky artist named Joe Petro III, whom Vonnegut says “saved [his] life” (143). Petro produces silk screen prints of line drawings and other artwork made by Vonnegut, and these works are sold by Origami Express, a partnership formed by the two men.

illustrations which appear in the book are the result of a relationship he had developed with a Kentucky artist named Joe Petro III, whom Vonnegut says “saved [his] life” (143). Petro produces silk screen prints of line drawings and other artwork made by Vonnegut, and these works are sold by Origami Express, a partnership formed by the two men.

Kurt Vonnegut died on April 11, 2007 after sustaining brain injuries from a fall at his Manhattan home.