Researching the South: Publications by C of C Faculty

2019-2020

Matthew Cressler wrote & co-authored a series of articles called Beyond the Most Segregated Hour; Reparations, Restructuring and Relationships for Religion News Service.

Adam Domby published, and gave myriad interviews about, The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory U of VA Press, and “Loyal Deserters and The Veterans Who Weren’t: Pension Fraud in Lost Cause ![[field_main_title]](https://www.upress.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/covers/5354_M.jpg) ” in Brian Jordan and Evan C. Rothera (ed.) The War Went On: Reconsidering the Lives of Civil War Veterans (LSU Press, April 2020). He also published “Counterfeit Confederates,” Civil War Monitor, Vol. 10, No. 3, Fall 2020; “The Lost Cause Was A False Cause,” Charleston City Paper, February 19, 2020: “Nikki Haley Gets The History of the Confederate Flag Very Wrong,” Washington Post, December 8, 2019.

” in Brian Jordan and Evan C. Rothera (ed.) The War Went On: Reconsidering the Lives of Civil War Veterans (LSU Press, April 2020). He also published “Counterfeit Confederates,” Civil War Monitor, Vol. 10, No. 3, Fall 2020; “The Lost Cause Was A False Cause,” Charleston City Paper, February 19, 2020: “Nikki Haley Gets The History of the Confederate Flag Very Wrong,” Washington Post, December 8, 2019.

Shannon Eaves co-authored “Tell the Stories of Those Who Have Enriched Charleston’s History,” with Adam Domby and Cappy Yarborough, Charleston City Paper, on July 1, 2020.

Julia Eichelberger published “Remembering and Rewriting Gullah Narratives,” introductory essay for U of SC’s 2020 edition of John Bennett’s collection of Gullah-inspired tales, The Doctor to the Dead.

Mary Jo Fairchild, Aaisha Haykal, and Barrye Brown (former C of C / Avery colleague) co-authored “Between Accession and Secession: Political Mayhem and Archival Transparency in Charleston, South Carolina” in the edited collection Libraries Promoting Reflective Dialogue in a Time of Political Polarization.

Grant Gilmore was in the news for his work creating N95 masks using 3D printers and then organizing their distribution to hospitals. A project he worked on with preservationists, historians and the family of Esau Jenkins culminated in September 2019 with the display of Esau Jenkins’s restored VW bus on the National Mall as part of the “Cars on the Capitol” series.

Photo of the Jenkins VW volkswagen as part of the “Cars on the Capital” project. Article by Nick Williams.

Joanna Gilmore contributed to an op-ed with Ade Ofunniyin and The Gullah Society, “Mayor Tecklenburg’s Comments on Charleston Protestors Not Helpful,” Post and Courier June 18, 2020.

Harlan Greene, Julia Eichelberger, and Ron Menchaca created Discovering Our Past: College of Charleston Histories, a map-based website commemorating the history of the College of Charleston and the spaces that are now part of its campus. With local researcher Sarah Fick and graduate student Grayson Harris, they researched stories for 13 locations and established a venue where future research on C of C can be made available to the public.

Harlan Greene published an essay in a collection, “To Make Their Own Way in the World”: The Enduring Legacy of Zealy Daguerreotypes”.

Maureen Hays co-authored The Stono Preserve’s Changing Landscape, Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, 2020.

Melissa Hughes co-authored “Continuously choosy mates and seasonally faithful females: sex and season differences underlie size-assortative pairing,” Animal Behavior 2020, vol. 160.

Gary Jackson wrote the poem “Forward and Back: Commemorating the 250th Anniversary of the College of Charleston.”

Adam Jordan writes a regular column, “Southern Schooling,” for The Bitter Southerner. All Y’all started a column as well; Adam’s 2020 posts (“Y’all Means All,” “Giving Voice to the Voiceless,” “Hillbilly Roll Call”) can be found here: https://www.allyalledu.com/pastcolumns. (Adam would probably have used his column to report on the All Y’all Social Justice Collective educators’ conference scheduled to be held in Charleston in July 2020, but COVID-19 had other plans.)

Joe Biden rally in South Carolina as part of the article “Why South Carolina Was So Personal for Joe Biden” by Dr Joe Kelly. Photo by Damon Winter.

Joe Kelly wrote an op-ed for the New York Times, “Why South Carolina Was So Personal for Joe Biden,” March 1, 2020. He and Rich Bodek co-edited Maroons and the Marooned: Runaways and Castaways in the Americas, University of Mississippi Press, 2020. Kelly wrote the Introduction and Chapter 9, “Maroons and the American Epic.”

Gibbs Knotts co-authored “Partisan Realignment and the Politics of Southern Memory,” forthcoming from LSE US Centre Daily Blog on American Politics and Policy, and “Switching Sides but Still Fighting the Civil War,” forthcoming from Politics, Groups, and Identities. He published “Rethinking the Charleston Runoff Requirement” in Charleston City Paper, November 20, 2019.

Gibbs Knotts and Jordan Ragusa co-authored First In the South: Why South Carolina’s Presidential Primary Matters with U of SC Press, and made numerous appearances discussing the book during primary season in Winter 2020. They also published “South Carolina Will Align the Democratic Calendar.” The Post and Courier, March 5, 2019, “Studying Politics in an Early State: Lessons from Being ‘First in the South.’” Political Science Now, January 9, 2020, and co-authored with Karyn Amira “Exit Poll: Overdevelopment and Flooding Motivated Charleston Voters. The Post and Courier, November 8, 2019.

Brittany Lavelle Tulla co-authored “Croxton at Kings Mountain: Implementation and Elaboration of the National Park Service Aesthetic,” Arris: The Journal of the Southeast Chapter of Architectural Historians, 2019, vol 30.

Simon Lewis continued to edit the journal Illuminations, with issue 35 including artwork and an interview with Charleston artist Colin Quashie.

Mark Long and Mark Sloan’s exhibit Southbound: Photographs of and About the New South has been exhibited in museums in North Carolina and Tennessee and is now at two museums in Meridian, MS. The Southbound catalog was honored with the Alice Award in 2019.

Kameelah Martin co-edited The Lemonade Reader: Beyonce, Black Feminism, and Spirituality, Routledge, 2019.

Anthony McCutcheon as Sam Maybank, Mario Richardson as Young Kofi and Asha Simmons as Mrs. Huger rehearse a scene from “The Cigar Factory.” From the article “Author Michele Moore adapts her novel “The Cigar Factory” into stage play” by Adam Parker.

Michele Moore’s novel The Cigar Factory was presented as a staged reading which sold out all performances at the Queen Street Playhouse in February. (See photos of cast in Post & Courier)

Harriet Pollack published “Evolving Secrets: The Patterns of Eudora Welty’s Mysteries” in Detecting the South in Fiction, Film, and Television, eds. Deborah Barker and Theresa Stuckey, University Press of Mississippi and edited New Essays on Eudora Welty, Class, and Race, December 2019, also with Mississippi. She edits a series for UP of Mississippi, Critical Perspectives on Eudora Welty.

Bernard Powers was interviewed for numerous articles including the City Paper’s August 12 2020 “Should We Be Talking About Reparations” and the Post and Courier’s podcast on the Calhoun Monument, which aired just as the monument was finally removed from its pedestal. His newest book, 101 African Americans Who Shaped South Carolina, will be out in October from USC Press.

The Office of Institutional Diversity created “If These Walls Could Talk,” a documentary about the creation of Randolph Hall and the College’s ties to slavery. English adjunct faculty member Michael Owens wrote the screenplay and OID’s Director of Diversity Education Charissa Owens was the producer of the documentary, which will be screened on campus this fall and features numerous C of C faculty sharing their expertise on enslaved workers and artisans in Charleston and at C of C.

The Pearlstine/Lipov Center for Southern Jewish Culture sponsored Research Fellows Daniel Gulotta, who studied archival materials on Isaac Harby and Andrew Jackson, and Jillian Hinderliter, who researched Southern Jewish Women & the Women’s Health Movement.

At 35 Chapel Street, current owner discusses renovation with students of the first year seminar class “Studying Abroad in Our Hometown.” Photos provided by seminar professor Dale Rosengarten.

Dale Rosengarten created “Studying Abroad in Our Hometown: A College of Charleston First-Year Seminar,” composed of students’ field trip logs from Spring Semester 2019 & published Sept 2019 as a downloadable PDF.

Hayden Ros Smith published Carolina’s Golden Fields: Inland Rice Cultivation in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1670-1860, Cambridge UP, 2019. He was advisor for the upcoming International African American Museum exhibit, “Carolina Gold,” and environmental historian for the NSF grant in progress, “Collaborative Research: Emergence and Evolution of a Colonial Urban Economy” (award number: 1920835).

Barry Stiefel and Nathaniel Walker organized the symposium Architectures of Slavery: Ruins and Reconstruction, held on campus in October 2019.

Robert Stockton wrote “Commerce and Class: New Approaches to Charleston History” (review essay), Journal of Urban History, 2020, Vol. 46(4) 914–921.

Nathaniel Walker co-edited Suffragette City: Women, Politics, and the Built Environment, Routledge, 2020.

Brian Walter wrote “Nostalgia and Precarious Placemaking in Southern Poultry Worlds: Immigration, Race, and Community Building in Rural Northern Alabama,” in Journal of Rural Studies ,December 2019.

Allison Welch co-authored “Development Stage Affects the Consequences of Transient Salinity Exposure in Toad Tadpoles,” Integrative and Comparative Biology, Oct 2019, vol. 59 no. 4. She also co-authored (with Wendy Cory)“Naproxen and Its Phototransformation Products: Persistence and Ecotoxicity to Toad Tadpoles (Anayrus terrestris), Individually and in Mixtures,” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2019, Vol 28, no 9.

Marjory Wentworth wrote a poem, “A Confederate Dialogue Between John C. Calhoun and Dylann Storm Roof,” in Charleston City Paper, June 18, 2020

Leah Worthington, Rachel Donaldson, and Kieran Taylor (Citadel), co-authored “Making Labor Visible in Historic Charleston,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas, March 2020, vol. 17, no. 1.

Event Highlights

2019

Between August 2019 and February 2020, the Bully Pulpit series, sponsored by the Department of Communication and moderated by Gibbs Knotts, hosted almost every Presidential candidate: Joe Biden, Michael Bennet, Elizabeth Warren, Andrew Yang, John Delaney, Cory Booker, Tulsi Gabbard, Bernie Sanders, Amy Klobuchar, Julian Castro, Beto O’Rourke, and Pete Buttigieg

Art piece by Katrina Andry for her exhibit “Over There And Here Is Me and Me”

August 23 to December 7 the Halsey Institute exhibited New Orleans-based artist Katrina Andry and Charleston-basedartist Colin Quashie

October 25 Groundbreaking of the International African American Museum (Bernard Powers, interm CEO; C of C alum Carlos Guzman Gonzales, Development Assistant); Inauguration of Dr. Andrew Hsu as C of C President, with inaugural poem by Gary Jackson

Sept 9-11 Susanna Ashton, Clemson English professor and author of works on slave narratives and African American writers as well as an LDHI exhibit, was on campus English Department’s Visiting Scholar.

Sept 12 4-6 Pm AAST Film Screening, Traces of the Trade

Sept 25 Presentation by Eric Crawford/Brigitta Johnson (music/ethnomusicology scholars who will discuss music in relation to Race, Religion, Resistance)

October 2-6 Association for the Study of African American Life & History ASALAH Conference (Embassy Suites Hilton, N Chas)

October 3 Charleston Museum/Gullah Geechee Meal with Chef Kevin Mitchell

October 24-26 2019 Conference The Architectures of Slavery: Ruins and Reconstructions at C of C, hosted by ARTH/HPCP (Nathaniel Walker, Barry Stiefel)

Nov 12 AAST’S Consuela Francis Lecture: Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh, speaking on religious culture, religious consciousness, and resistance among enslaved Black women in the South.

2020

Art piece by Butch Anthony Seale from his exhibit “Inside/Out”

January 17-Feb 29 Halsey Gallery exhibits Alabama artist Butch Anthony and quilting artist Coulter Fussell

January 30 2020 C of C Founder’s Day & celebration of College’s 250th anniversary. Events included presentation of Founder’s Day Medals (to the Hon. Lucille Whipper, J. Waties Waring (posthumous), and Spoleto USA), followed by State Historic Marker unveiling on George Street.

On January 30, 2020 The College of Charleston celebrated CofC Day with a full day of events.

February 19 Gibbes Museum program “She Persisted: Women of Letters and the American South” with Julia Eichelberger, Michele Moore, and Nikky Finney, in conjunction with exhibit “Central To Their Lives: Southern Women Artists in the Johnson Collection”

Feb 21 Southern Studies minors Tanner Crunelle, Grayson Flowers, Michael Lucero, Trevor Pearson, and Liz Whitworth present their SOST 400 Capstone research projects in Addlestone Library 220

[March 2020 College closes campus due to COVID-19; all faculty pivot to online instruction, and new approaches are developed to introduce students to archival research and experiential learning]

June 9 Southern Studies program issues its statement “Say Their Names” in solidarity with and all those protesting against the murders George Floyd and other victims of racist violence

June 20 Bernard Powers and Robert Rosen propose a counter-monument honoring African American heroes as a response to the monument to the “Confederate Defenders of Fort Sumter”’

June 22 President Hsu convenes a Historical Review Task Force

June 24 Calhoun Monument is removed from Marion Square

July 13-17 LGBTQ Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon is organized by Special Collections

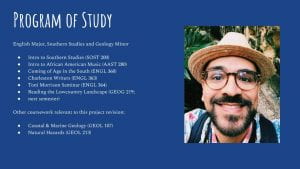

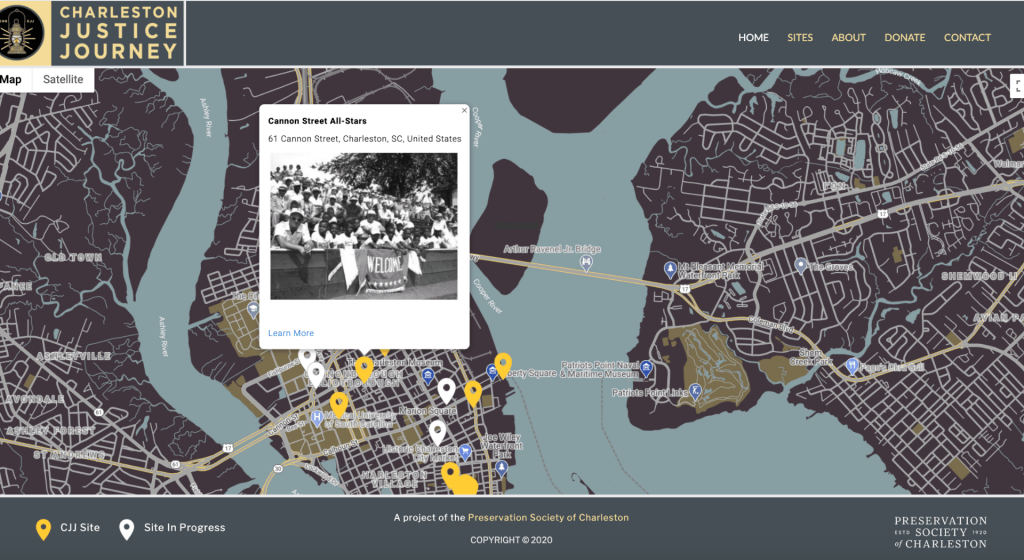

August 2020 Southern Studies minors Grayson Flowers, Tanner Crunelle, and Stella Rounsefell share their experiences in the minor, plans for the future, and current careers.

GEOL 213 – Natural Hazards – Steven C. Jaume’ – MWF 12:00 – 12:50

GEOL 213 – Natural Hazards – Steven C. Jaume’ – MWF 12:00 – 12:50

manor and hope to return stronger than ever with more chances for student involvement in the future. The ship played host to the Port Cities Conference and still stands as a point of pride in the harbor. It represents not only where we came from but rather what we are, as it offers both the public and students an interactive window into history. Sure to be a unique way to see the world both now and then, the Semester at Sea program hopes to return once it is safe to do so. To learn more and to see what it’s like to live out a Semester At Sea, check out the video!

manor and hope to return stronger than ever with more chances for student involvement in the future. The ship played host to the Port Cities Conference and still stands as a point of pride in the harbor. It represents not only where we came from but rather what we are, as it offers both the public and students an interactive window into history. Sure to be a unique way to see the world both now and then, the Semester at Sea program hopes to return once it is safe to do so. To learn more and to see what it’s like to live out a Semester At Sea, check out the video!

![[field_main_title]](https://www.upress.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/covers/5354_M.jpg) ” in Brian Jordan and Evan C. Rothera (ed.) The War Went On: Reconsidering the Lives of Civil War Veterans (LSU Press, April 2020). He also published “Counterfeit Confederates,” Civil War Monitor, Vol. 10, No. 3, Fall 2020; “The Lost Cause Was A False Cause,” Charleston City Paper, February 19, 2020: “Nikki Haley Gets The History of the Confederate Flag Very Wrong,” Washington Post, December 8, 2019.

” in Brian Jordan and Evan C. Rothera (ed.) The War Went On: Reconsidering the Lives of Civil War Veterans (LSU Press, April 2020). He also published “Counterfeit Confederates,” Civil War Monitor, Vol. 10, No. 3, Fall 2020; “The Lost Cause Was A False Cause,” Charleston City Paper, February 19, 2020: “Nikki Haley Gets The History of the Confederate Flag Very Wrong,” Washington Post, December 8, 2019.