You’ll remember my appeal in class Tuesday for you to help the English Department hire a new Composition/Rhetoric specialist. So please, if you can, head over to the Student & Faculty Lounge (back of 26 Glebe Street, corner of Glebe and George Streets) on Wednesday, Friday and/or Monday between 2 and 3, to give our candidates a sense of what our students are like. We’ll have treats to make it even more worth your while!

Monthly Archives: February 2016

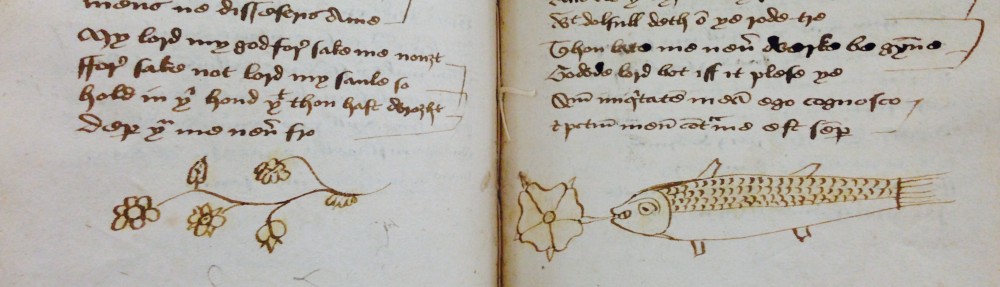

Messing with Meaning, Secondary Authors

The discussion of the Sir Gawain images on page 186 of OUMEM really brought the illustrator’s influence to life for me. It says, “In the bottom register Gawain on his horse replicates the Green Knight on his horse in the prefatorial miniature, as if their identities had been exchanged or as if the one is a doppelganger or dark side of the other.” This type of image, especially if viewed before reading the story, could have a profound impact on how it was read. Imagine a few different depictions the illustrator could have used. What if he would have made the Green Knight a humongous hulking figure with a cruel-looking axe posed over Gawain. Wouldn’t that incite a different understanding than, say, a picture of Gawain holding the enchanted belt toward the sky and crying? In the first case, people would probably tend to be impressed with the terror that Gawain would be facing- the physical danger he would encounter and how he would stand up to it. In the second option, however, the viewer might be tempted more toward an understanding of Gawain’s chivalric struggle- the mental turmoil he felt at betraying his own code of honor (or, at least, at being caught).

Mistake or Message?

A few classes ago Dr. Seaman noted that most people will look at these miniatures and say: “God wasn’t it great when artists learned perspective?” Not to lie I thought it. But our reading seems offer other explanations for the strange situation of some images: especially images of the environment and the background (the trees/rivers/hills). In the miniatures from the Pearl MS. the hillside actually shifts, at first it slopes from the lower left corner of the page to the upper right; then the hill shifts and it runs from the upper left to the lower right. It’s inconsistent, but not a mistake. The anthologists postulate that the artists was changing perspective because “the perceptions of the dreamer […] changed” (177). Still the rivers look strange the way they simply chop across the page. But I do notice that the river functions as impassible band, like a break in the image (I’m imagining the way comics and movies depict phone calls: where one caller is separated from another by a jagged band across the screen). Indeed, the anthologists suggest that there is further weight to the rivers: that they are meant to suggest the roundness of the Earth (178). When I read that I had to pause for a moment. They go on to explain that it replicates the shape of the Mandorla which often encircles christ. These rivers look flat and childlike to me, they seem careless almost, but then you read this book and you learn that’s not so. Shockingly there was great attention to detail, despite the painting of fingers.

What is the Importance of the “spot” ?

In my readings tonight, one thing that I found very intriguing was the images that were found in the Pearl poem with the man dreaming by the river. One thing that really caught my attention was the “spot” that they kept referring to. Looking at the image, initially I didn’t see any major significance’s of the spot. To me, it just seemed like a darker part of the hill like a river or some sort. I didn’t think that it had any major importance. But after reading through the chapter, it became clear to me what the spot represented in reference to the poem itself. I thought that it was very interesting that something so small and insignificant could have so much importance on the image as a whole. When the writer began to analyze the spot and say that it was a representation of either the grave of the dreamer’s daughter, the portal to heaven, or the place where he initially dropped the Pearl, it made me think how amazing it was for the artist to add in such a small and somewhat insignificant detail, but he created it in a way that made it seem so important.

Another thing about this image that I found very interesting was the idea of the aquamarine color that was supposedly not there in the original. This brings back more interest towards the spot. One question that this posed in my mind was what was the purpose of adding the spot later? If the original artist did not put this small detail into the original piece, then why did another artist find it important to add in later? The spot posed a lot of curiosity in my mind and I would really like to gather more information on it and who drew in the spot and why? Was it just a mistake on the part of the first artist? Or was it something that needed to be added for a different reason. This is definitely something that I want to find out more information on.

Sir Gawain and Satire: A story of subtlety

It seems that much of the discourse revolving around Sir Gawain pertains to the moralistic conflict our protagonist faces by the story’s end. Although this conversation is significant in context of our typical understanding of knighthood and the tales preceding Sir Gawain, I think the author potentially produced this document in resistance to the chivalric narrative. In a way, the author takes the advantageous circumstances awarded to the preceding narratives and throw them away, sort of saying “okay, Knights of the Round Table, what now?”

It’s important to understand this form of satire as one which aims not to parody the chivalric value of the knights, but instead aims to test their chivalry when their “gaming” mentality is turned against them. In Sir Gawain’s case, he is completely at the mercy of the Green Knight, who seems to possess abilities which strip Sir Gawain of the types of agency normally afforded to knights in other tales.

The most obvious type of agency taken from Gawain is his ability to control through physical force. Gawain could be the biggest, strongest, fastest knight with the most effective weapons and armor in the game, but it would serve him no purpose against a man who survives decapitation of all injuries, and it does not bode well for him as a character whose archetypal victory should be “slaying” the enemy. We most notably see where this becomes an issue toward the end of the story, where Sir Gawain’s moral dilemma to take the green belt coincides with his dilemma over whether to accept the Green Knight’s evaluation. Moral issues aside, Sir Gawain’s survival comes at his dismay when he realizes the green belt was given as a part of the Green Knight’s grand design. It would have been one thing for Gawain to endure his enemy’s physical strike by his own cleverness, but for the “magic” to come from that very enemy only buttresses the level of control the Green Knight.

Although this sort of “bracketing” of control may not fit our notions of satire, I think there is something to be said of the truths our author reveals through the Green Knight. When Gawain goes back home, his fellow knights cannot help but to celebrate his return within the context of chivalric victory. Because they haven’t been subject to the control Gawain was subject to, Gawain is just left to think, “dude, you guys totally don’t get it.” I’m not sure if you can call that satire, but it’s pretty hilarious in my mind.