This week’s postings and readings have led me to a lot of questions. First, to expand on the concept that Annette proposed earlier, how do you apply the concept of resilience in environmental management practices? First, it is important to mention that the resilience framework that we used for this week seems to only apply to ecological resilience – and not the grander socio-ecological systems resilience. Even beyond the conceptual model that we have discussed earlier, is the evidence that Hull et al. (2002) provided that suggests that the practitioners in Virginia surveyed believe that they are in some way separate from nature. Respondents stated that they either believed that nature should be or should not be controlled by humans. Regardless, both responses insinuate that humans are outside of the system and never within it. It is clear from the responses from Laura and Andrew that humans *are* part of the system, which leads me to believe that to the first step in incorporating resilience into new management regimes is to acknowledge and incorporate the direct and indirect activities of humans. Moreover, this means that management must move beyond a solely ecological approach to a systems approach, which I briefly reviewed in my earlier post.

Next, should management practices be revised? I think the answer resonates within the words of my peers as well as the ideas from the readings; yes! To merge the ideas from Schafer & Carpeneter (2003) and Bengtsson et al. (2003), environmental systems are always undergoing some sort of change at different spatial and temporal scales at the whim of different drivers. Moreover, the latter authors outline the reasons for this need clearly throughout their work. They explicitly state that there is no environmental system that fits in a perfectly prescribed box by management practitioners or policy makers. Therefore, it makes no sense to impose management regimes that create static reserves – especially ones that remove human activities from the equation. Here I wonder if our management practices were born from the observations of “stable states”, which are actually snapshots of larger cyclical behaviors and regime shifts, and therefore appear static when isolated by typical human subjectivity. Is seems that only recently have humans begun to understand the fallacy of this perspective.

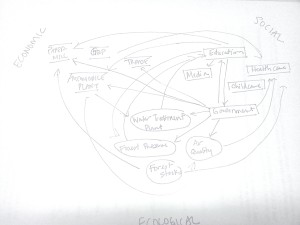

Now, the more difficult question becomes how do we manage dynamic and unpredictable environments? Yes, Schafer & Carpenter suggests using models, but I’m unsatisfied. From the onset, the idea seems a bit contradictory – to manage something that you barely understand, but know is wild, erratic, and latently volatile. Also, this idea might explain why Hull et al. discovered the data that they did from their survey, what Bengtsson et al. identify as a “classic view”. Is it too difficult to manage something that you are a part of, yet seemingly separate? This is especially the case in environments like those described by Bengtsson et al., where the reserve separates people from the physical space, again seemingly so and not actually so. This of course lies in contrast to environments like those described by Laura, Andrew, and Annette, where people’s existence is so obviously tied into the physical natural environment. It possibly makes more sense that the answer to the question lies somewhere in the middle of all of this – somewhere between observing the lessons from nature and acknowledging our place as well. What stands out to me this week is that the goal of management should not be to retain systems, but to somehow support their resiliency. I suppose this is the golden question of the week, of the year, and even of the decade. However, both Schafer & Carpenter and Bengtsson et al. bring us a little bit closer to an answer when they note that multiple approaches should be used in parallel. This ideal may seem commonsense to many of us, but clearly is not adopted on a mainstream scale.