By Sarah Boessenecker (@tetrameryx)

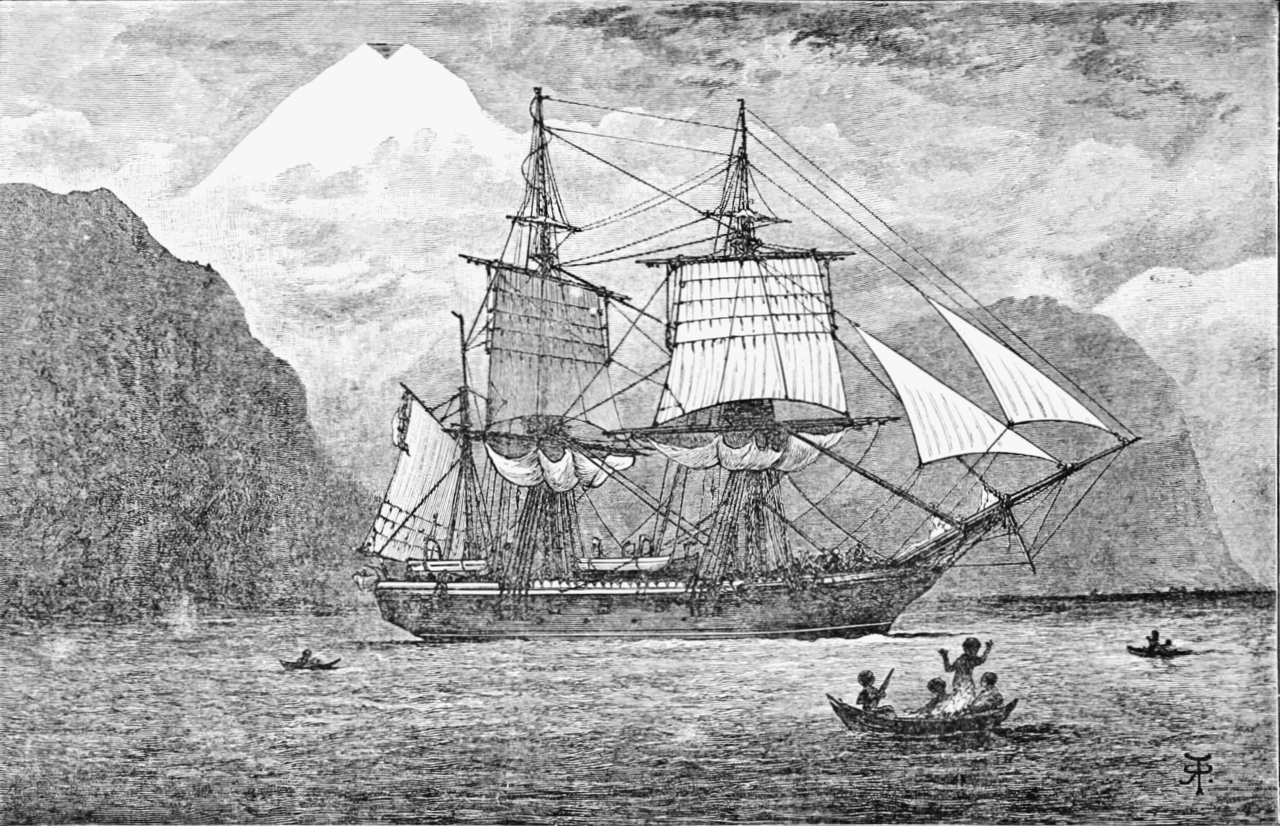

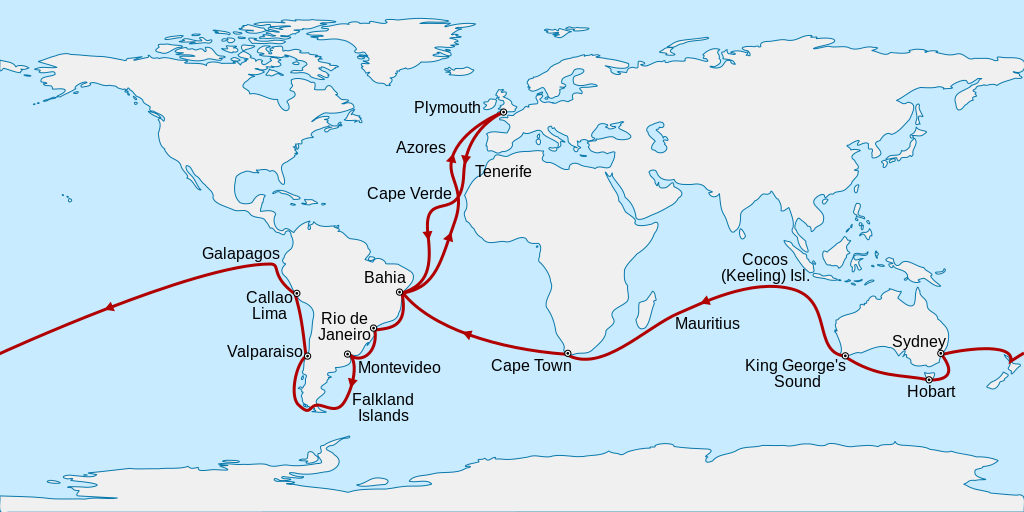

When Darwin finally returned to England in October of 1836 after 5 years away on the HMS Beagle, he found he was already a rising star. Darwin had sent letters, notes, and musings to his former professor John Henslow, who recognizing the significance of them, passed them on to a group of fellow scientists and naturalists. He had also given a copy to Charles Darwin’s father Robert, who had initially opposed Darwin going on this trip. According to Henslow, Darwin’s father “did not move from his seat till he had read every word of your book & he was very much gratified – he liked so much the simple clear way you gave your information.”

Darwin spent a short time catching up with his family, and then headed to Cambridge to meet with Henslow. Henslow encouraged Darwin to find other naturalists to curate and catalog the collection of specimens he had amassed while on the Beagle, and agreed to take the botany specimens for him. Robert Darwin, now impressed with the scope of his son’s work, funded Darwin and helped him to find suitable institutions for his collection. Darwin worried about the backlog of work many museums had, and fretted that his specimens would remain in storage for some time.

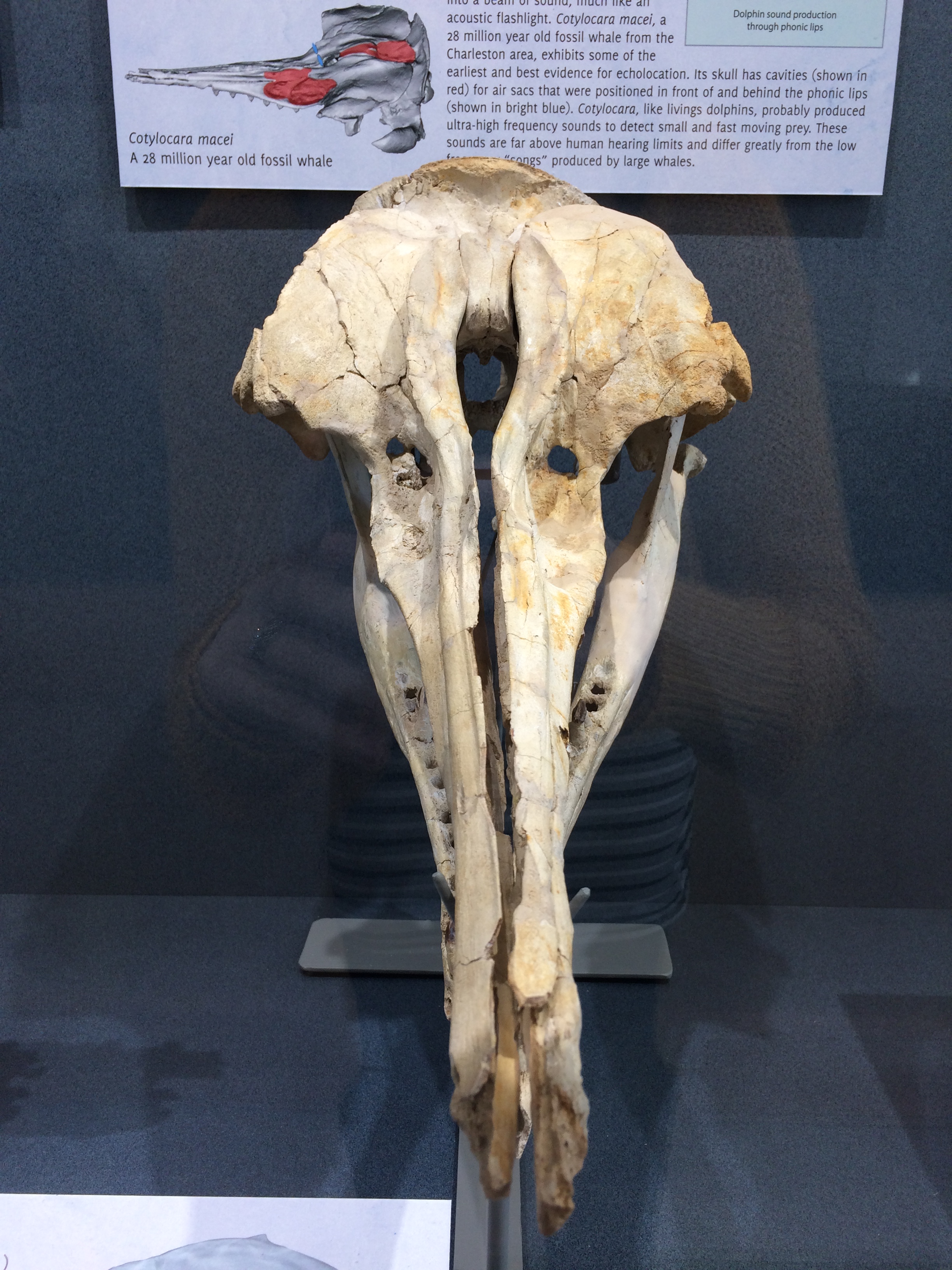

Darwin was put in touch with up-and-coming anatomist Richard Owen at the Royal College of Surgeons. Owen eagerly accepted the fossils Darwin collected while in South America and his findings came as a shock to Darwin, and would also help contribute to his theory of evolution.

Owen studied the fossils Darwin had brought back with him, and described giant sloths such as Megatherium (well-known by this time), the related, but undescribed Scelidotherium, a large capybara-like rodent named Toxodon, and fragments of the armor from the giant armadillo-like creature called Glyptodon, as well as new species of Mastodon. Owen found that these creatures were related to species still living in South America, rather than related to similar-sized animals living in Africa as Darwin thought. These findings would play a key role in Darwin’s views on life and species and change over time.

Darwin’s return to England was an incredibly busy time; eager to discuss his ideas he had contrived while traveling he met again with Charles Lyell and was encouraged to write a paper; on January 4th, 1837 he read this paper to the Geological Society in London, describing the processes of the South American landmass gradually rising, as well as the formation of coral atolls. Darwin had been nervous to present his findings, but they were well received, and he felt “like a peacock admiring his tail.”

That same day, Darwin went on to present the 80 mammal and 450 avian specimens he had collected over the voyage to the Zoological Society. Ornithologist John Gould took special interest in the bird specimens, taking particular care to study the many specimens collected from the Galápagos Islands. His results were groundbreaking; when the Zoological Society met again on January 10th, Gould proposed that the collection of blackbirds, finches, and wrens Darwin had described were instead “a series of ground Finches which are so peculiar [as to form] an entirely new group, containing 12 species”. They later became known as “Darwin’s Finches,” and were featured in local newspapers, though Darwin was traveling to Cambridge again and didn’t learn of this until sometime later. In fact, it wasn’t until March when Gould and Darwin were again able to meet up, and Darwin got the full report of Gould’s findings; he learned the Galápagos ‘wren’ was in fact another species of finch, and that the many types of mockingbirds Darwin noted were in fact separate species, rather than just varieties as he had believed. In fact, Gould had found many more species than Darwin had expected, including 25 of the 26 land birds Darwin had recorded were in fact different species, and found no where else in the world, though they were closely related to species found in South America. Darwin realized the sheer abundance of species found on the islands was due to the fact that they were confined to the islands with little mixing; he wrote to the crew members asking for specimens they had collected, and which island they had come from. This information he collected helped solidify his thoughts on transmutation of species, and he began compiling a series of notebooks organizing his thoughts and theories.

Darwin’s finches, showing the different beak sizes and adaptations. Image from WikimediaCommons.

He later wrote,

“The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands, is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species. [In] the Galápagos Archipelago… almost every product of the land and water bears the unmistakable stamp of the American continent. There are twenty-six land birds, and twenty-five of these are ranked by Mr. Gould as distinct species, supposed to have been created here; yet the close affinity of most of these birds to American species in every character, in their habits, gestures, and tones of voice, was manifest…. The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, yet feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galápagos Archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plain a stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height or climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which resembles closely the conditions of the South American coast: in fact there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in climate, height, and size of the islands, between the Galápagos and Cape de Verde Archipelagos: but what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape de Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galápagos to America. I believe this grand fact can receive no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation; whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galápagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists, whether by occasional means of transport or by formerly continuous land, from America; and the Cape de Verde Islands from Africa; and that such colonists would be liable to modification;—the principle of inheritance still betraying their original birthplace.”

On February 17th, 1837 Darwin attended a meeting of the Geological Society where Charles Lyell gave the presidential address. Lyell presented Owen’s findings on the fossils Darwin had collected, stating he saw “law of succession” with mammals replacing one another on their continents, inferring that extinct species were in fact related to modern living species. This speech caused Darwin to ponder why past species and modern species should be so closely related from the same locality. At this meeting Darwin was also elected onto the Council of the Society, which Lyell described as “a glorious addition to my society of geologists.”

By early March, Darwin had moved to London to be near his work. Moving to London also allowed Darwin to join the social circle of Lyell, which included prominent and influential scientists. Darwin stayed with his brother Erasmus, who was a free-thinker and friends with radical thinkers who shared his ideas, which was not typical for people of these times.

During all this time Darwin had still been organizing his thoughts and notes about species and transmutation. In his ‘red notebook’ he hypothesized that “one species does change into another” and thought this may explain why the fossils he found were similar to species still living in those geographic areas; he wondered why the territories of some species overlapped without intermediate species. He wondered if mutations “present an analogy to production of species,” which was bold and dangerous to say; his previous geology professor Adam Sedgwick considered those who held the same views as “infidel naturalists..[adopting] false theories.” Lyell felt such views as blasphemy, as they implied ape ancestry and destroyed mankind’s “high estate.”

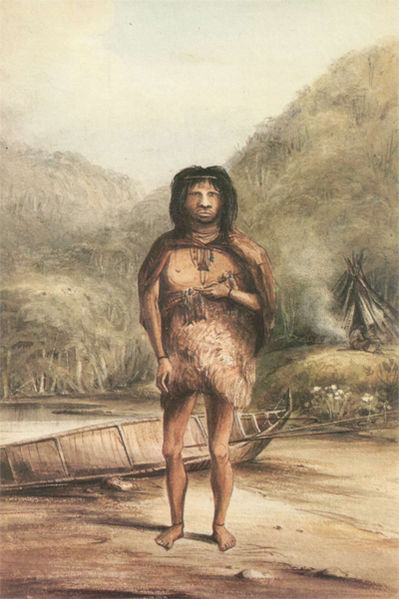

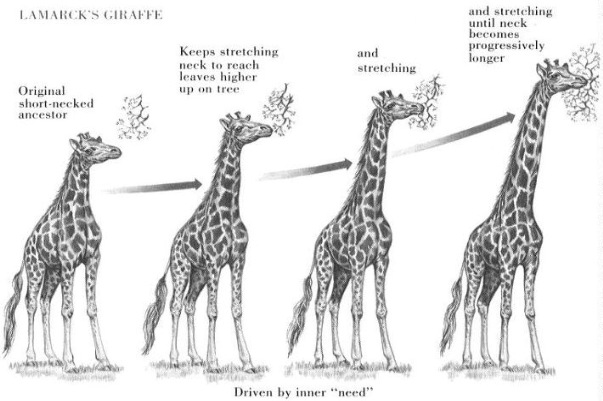

In London, Darwin visited the zoo and saw an ape for the first time and wrote, “Let man visit Ourang-outang in domestication, hear expressive whine, see its intelligence…. let him look at savage…naked, artless, not improving yet improvable & let him dare to boast of his proud preeminence.” He thought back again on the natives of Tierra del Fuego, and dared to think there may be little separation between man and animals, going against the theological doctrine. He often wondered about how the ‘savage’ natives from Tierra del Fuego could be “essentially the same creatures” as the more civilized Europeans. At the Geological Society meeting in May of 1837, the first fossil monkeys were announced. This made Charles Lyell uncomfortable, joking that from “Lamarck’s view” it gave the time necessary “for their tails to wear off.” Darwin, however, found these new discoveries fascinating and looked at them in a new evolutionary way.

By July Darwin had started a new notebook on “transmutation of Species” which was also known as his ‘B Notebook.,’ and was inspired by being “greatly struck from about month of previous March on character of S. American fossils — & species on Galápagos Archipelago. — These facts origin (especially latter) of all my views.” He wrote down his many ideas about lifespans and the age of species, including notes on Owen’s theory that the complexity of an organism was inversely related to its lifespan. Darwin compared sexual reproduction to asexual reproduction, and argued that while asexual reproduction resulted in direct copies of an individual, sexual reproduction allowed for variation in offspring, which enabled the organisms “to adapt & alter the race to changing world.” This, he reasoned, could help explain why the tortoises on the Galápagos islands were all similar, but still different species. He sketched his first evolutionary trees, and wrote “It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another.” Darwin was convinced life arose only once, and dismissed the ideas of different lineages giving rise to higher forms, as proposed by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Robert Edmond Grant. He also disagreed with Lamarck’s hypothesis of gradual change, and instead believed that there was a clear distinction between species, no matter how closely related they were. Darwin believed that new species emerged in a form perfectly adapted to their environment, and cited the Galápagos tortoises again. He reasoned that they all shared a common ancestor, and each island had its own species that was perfectly suited to that individual island.

Darwin felt common ancestry was undeniable, especially when looking at animals like the duck-billed platypus, but still held the belief that there was a Creator behind everything. He argued that the Creator was the reason that there were so many unique animals on the Galápagos that still shared traits with those on the mainland, but wandering species like the sandpiper were unchanged from region to region. Darwin thought about how astronomers once believed that God ordered the movement of individual celestial bodies, and felt that it was comparable to God creating individual species for a particular country; he wrote that the divine powers were “much more simple & sublime” when the first animals were created, and new species arose by “the fixed laws of generation.” He saw these new species as “fresh creations” and wrote his hypothesis was “mere assumption, it explains nothing further.”

Darwin continued to do his research living in London, and read papers by Thomas Robert Malthus, such as the 6th edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population. A central thesis of this publication was that “population, when unchecked, goes on doubling itself every twenty five years, or increases in a geometrical ratio.” He compared these ideas with those of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle’s, noting the “warring of the species” and the struggle for existence for species. He reasoned that as species bred beyond available resources, those with favorable variations would be more likely to survive and pass those variations on to their offspring, and those with less favorable variations would not pass them on. Darwin wrote,

“In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population, and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then, I had at last got a theory by which to work…”

Darwin observed farmers picking their best stock to reproduce, questioning whether they were going against nature by “picking varieties.” He noted that “every part of newly acquired structure is fully practical and perfected,” and feeling that this observation was “a beautiful part of my theory, that domesticated races of organics are made by precisely same means as species – but latter far more perfectly & infinitely slower.” He named this theory ‘natural selection,’ and suggested ideas of adaptations to climate. He read a pamphlet by Sir John Sebright which stated, “A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection. In cold or barren countries no animals can live to the age of maturity, but those who have strong constitutions; the weak and the unhealthy do not live to propagate their infirmities.” Darwin reflected on those “excellent observations of sickly offspring being cut off so that not propagated by nature,” and wrote, “the whole art of making [domestic] varieties” in relation to farmers selecting mates to breed ornamental ducks was “a mere monstrosity propagated by art.” He referred to this practice by farmers as ‘artificial selection.’

Darwin continued to speculate about human evolution, and worried about the social implications of doing so. He wrote, “Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work, worthy the interposition of a deity, more humble & I believe true to consider him created from animals,” and drew parallels with grinning, saying it was “no doubt a habit gained by formerly being a baboon with giant canine teeth… Laughing modified barking, smiling modified laughing. Barking to tell [troop] good news. discovery of prey. – arising no doubt from want of assistance. – crying is a puzzler.”

Darwin thought about “innumerable variations” mankind had ‘acquired’ and hypothesized that vestigial organs, such as the coccyx (tail bone) were not merely God “rounding out his original thought [to its] exhaustion,” which was the leading thought of the time, but rather remnants from “the parent of man.”

It wasn’t until June of 1843 that Darwin would begin to solidify these thoughts in writing, in his ‘Pencil Sketch’ of his theory. He wrote,

“From death, famine, rapine, and the concealed war of nature we can see that the highest good, which we can conceive, the creation of the higher animals has directly come. Doubtless it at first transcends our humble powers, to conceive laws capable of creating individual organisms, each characterised by the most exquisite workmanship and widely-extended adaptations. It accords better with [our modesty] the lowness of our faculties to suppose each must require the fiat of a creator, but in the same proportion the existence of such laws should exalt our notion of the power of the omniscient Creator. There is a simple grandeur in the view of life with its powers of growth, assimilation and reproduction, being originally breathed into matter under one or a few forms, and that whilst this our planet has gone circling on according to fixed laws, and land and water, in a cycle of change, have gone on replacing each other, that from so simple an origin, through the process of gradual selection of infinitesimal changes, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been evolved.”

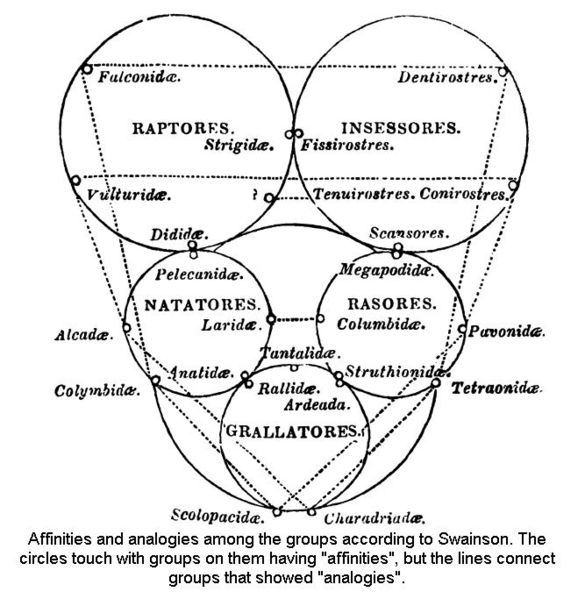

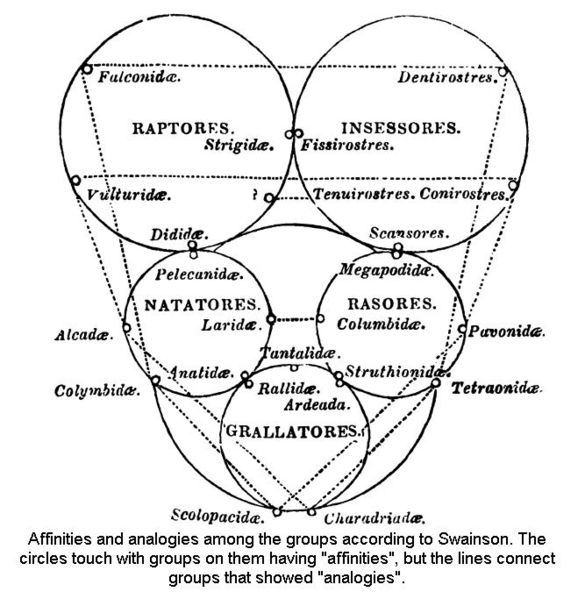

In May, George Robert Waterhouse wrote to Darwin requesting advice on classification. Darwin wrote it “consists in grouping beings according to their actual relationship, ie their consanguinity, or descent from common stocks,” and in another letter wrote, “all the orders, families & genera amongst the Mammals are merely artificial terms highly useful to show the relationship of those members of the series, which have not become extinct.” He asked this letter to be returned, for fear of his ideas being labeled as heresy. Waterhouse was a follower of Richard Owen, who was a proponent of the Quinarian System, (a short-lived belief that corralled all taxa into 5 subgroups, shown in circles with those closer together representing greater affinities and with the ‘higher classifications’ at the top) and attacked Darwin’s ideas in a paper.

A Quinarian diagram detailing ornithological relationships. Image from WikimediaCommons.

Darwin became friends with botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, and wrote to him in a letter in January of 1844. He facetiously wrote that he was “almost convinced (quite contrary to opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable. Heaven forfend me from Lamarck nonsense of a ‘tendency to progression’ ‘adaptations from the slow willing of animals'” &c,—but the conclusions I am led to are not widely different from his—though the means of change are wholly so— I think I have found out (here’s presumption!) the simple way by which species become exquisitely adapted to various ends.” Hooker responded guardedly with, “There may in my opinion have been a series of productions on different spots, & also a gradual change of species. I shall be delighted to hear how you think that this change may have taken place, as no presently conceived opinions satisfy me on the subject.”

Darwin also wrote to Reverend Leonard Jenyns, also a naturalist and someone Darwin had known since his time at Cambridge. He wrote,

“work on the species question has impressed me very forcibly with the importance of all such works, as your intended one, containing what people are pleased generally to call trifling facts. These are the facts, which make one understand the working or œconomy of nature …. namely what are the checks & what the periods of life, by which the increase of any given species is limited.”

He also wrote,

“continued steadily reading & collecting facts on variation of domestic animals & plants & on the question of what are species; I have a grand body of facts & I think I can draw some sound conclusions. The general conclusion at which I have slowly been driven from a directly opposite conviction is that species are mutable & that allied species are co-descendants of common stocks. I know how much I open myself, to reproach, for such a conclusion, but I have at least honestly & deliberately come to it. I shall not publish on this subject for several years.”

He cautiously told Jenyns that “With respect to my far-distant work on species, I must have expressed myself with singular inaccuracy, if I led you to suppose that I meant to say that my conclusions were inevitable. They have become so, after years of weighing puzzles, to myself alone;; but in my wildest day-dream, I never expect more than to be able to show that there are two sides to the question of the immutability of species, ie whether species are directly created, or by intermediate laws, (as with the life & death of individuals).”

He told Jenyns of the 200 page essay he had written on the subject, writing that he had “drawn up a sketch & had it copied (in 200 pages) of my conclusions; & if I thought at some future time, that you would think it worth reading, I shd. of course be most thankful to have the criticism of so competent a critic.”

Jenyns never offered to critique the essay, but warned Darwin on the use of the word ‘mutation,’ to which Darwin replied, “it will be years before I publish, so that I shall have plenty of time to think of better words.”

Darwin worked on many other publications during this time, detailing his findings from his voyage with the Beagle, and was often delayed in research due to repeated bouts of illness. Darwin had seen disgrace brought to other scientists who had made similar claims, and wanted to be certain he could answer all objections to his theory before he published. It wasn’t until September of 1854 that Darwin’s other works were wrapped up enough he could fully devote his attention to his theory and the write-up of it. He was still getting other scientists and friends accepting of his idea fully, and this was a slow process.

In early 1856, Lyell read the paper On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species, written by naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace, and caused Lyell to reevaluate his doubts on evolution. He hurriedly wrote to his friend Darwin, who had taken little interest in Wallace’s writings at the time. Darwin had been busy finalizing his theory to present it in full, and gave the details in full to Lyell. Lyell still could not fully accept the theory, but encouraged Darwin to publish with haste to establish priority. Darwin was conflicted between having his idea presented in full for publication, or getting a paper published quickly.

By mid 1856, Darwin had decided to publish a full treatise on species, and Lyell had begun to come around to accepting the idea of evolution, though he was still conflicted over the social implications of human and animal shared ancestry, especially as race issues were starting to appear, and there were worries of racial wars.

Darwin continued discussions within his scientific circle, and by 1857 he and Wallace had been in contact, with Wallace sending bird specimens from Indonesia to Darwin. Darwin wrote to Wallace,

“I can see that we have thought much alike & to a certain extent have come to similar conclusions…This summer will make the 20th year (!) since I opened my first note-book, on what way do species & varieties differ from each other…I am now preparing my work for publication…do not suppose I shall go to press for two years…I have slowly adopted a distinct & tangible idea,– whether true or false others must judge.”

Darwin had many fellow scientists who held him in high regard, and aided by sending him more information. Asa Gray worked on plants, and Darwin wrote to Gray stating that species “have descended from other species, like varieties from one species” and “that species arise like our domestic varieties with much extinction.” Darwin also wrote he had “come to the heteredox conclusion that there are no such things as independently created species – that species are only strongly defined varieties. I know that this will make you despise me. – I do not much underrate the many huge difficulties on this view, but yet it seems to me to explain too much, otherwise inexplicable, to be false.” Gray was intrigued, but didn’t fully grasp the enormity of what Darwin was proposing. Darwin was asked if these ideas could be presented at the Geological Society, but Darwin was still not ready, wanting his case fully prepared before it was presented.

In December of 1857, Wallace wrote to Darwin questioning if he were going to discuss human evolution in his paper. Darwin responded with, “I think I shall avoid the whole subject, as so surrounded with prejudices, though I fully admit that it is the highest & most interesting problem for the naturalist.” Darwin continued working tirelessly on his publication, well into the new year.

In June of 1858, Darwin received a package from Wallace. In it was 20 pages or so of text describing an evolutionary mechanism, with request to send it on to Lyell. Darwin was shocked, and wrote to Lyell,

“Some year or so ago you recommended me to read a paper by Wallace in the ‘Annals,’ which had interested you, and, as I was writing to him, I knew this would please him much, so I told him. He has to-day sent me the enclosed, and asked me to forward it to you. It seems to me well worth reading. Your words have come true with a vengeance–that I should be forestalled. You said this, when I explained to you here very briefly my views of ‘Natural Selection’ depending on the struggle for existence. I never saw a more striking coincidence; if Wallace had my MS. sketch written out in 1842, he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters. Please return me the MS., which he does not say he wishes me to publish, but I shall, of course, at once write and offer to send to any journal. So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed, though my book, if it will ever have any value, will not be deteriorated; as all the labour consists in the application of the theory.

I hope you will approve of Wallace’s sketch, that I may tell him what you say.”

While Wallace’s theory was similar to Darwin’s, the mechanism for selection relied on the environment more so than individuals competing. Darwin knew not publishing immediately would cause him to lose priority, but it would be dishonorable to “publish from privately knowing that Wallace is in the field.” He wrote to Lyell requesting advice, arguing he had written to Gray in 1857, and had originally sketched his idea as early as 1844 in a letter to Hooker, “so that I could most truly say and prove that I take nothing from Wallace. I should be extremely glad now to publish a sketch of my general views in about a dozen pages or so. But I cannot persuade myself that I can do so honourably… I would far rather burn my whole book than that he or any man should think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit”.

Lyell and Hooker agreed to publish a joint paper with Darwin at the next meeting of the Linnean Society in July of 1858, as they were all members and on the council. The evening before the meeting, Lyell and Hooker forwarded on the papers by both Wallace and Darwin to the society’s secretary to both be read at the meeting, complete with extracts from Darwin’s letter, and wrote a short introductory statement.

These joint papers were titled On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection, written by Wallace and Darwin respectively, and were read to the Society by the secretary before reading 6 other papers. There was no discussion of the papers after the readings, though it is unclear if this is due to the amount of business that needed covered at the meeting, or if it was reluctance for members to question the prominent figures of Joseph Hooker and Charles Lyell. Thomas Bell, who had written up and described the reptile specimens Darwin brought back from his voyage on the Beagle presided over the meeting and had apparently disapproved of Darwin’s and Wallace’s ideas; in his presidential report in May of 1859 he wrote, “The year which has passed has not, indeed, been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, the department of science on which they bear.” However, the vice-president of the society was quick to remove any remarks of transmutation from his papers awaiting publication.

Others also were coming around to this idea; prominent zoologist and chair of the Zoology and Comparative Anatomy department of Cambridge from 1866-1907 Alfred Newton wrote, “I sat up late that night to read it [the Linnean Society paper]; and never shall I forget the impression it made upon me. Herein was contained a perfectly simple solution of all the difficulties which had been troubling me for months past. I hardly know whether I at first felt more vexed at the solution not having occurred to me than pleased that it had been found at all.” Newton was convinced and became a follower of Darwinian evolution for the rest of his life.

Wallace was also extremely pleased with the outcome of the meeting, writing that he would have had “much pain & regret” if the papers had been published separately, and Darwin assured Wallace that it “had absolutely nothing whatever to do with leading Lyell and Hooker to what they thought was a fair course of action.” When Wallace inquired about Lyell’s thoughts on the papers, Darwin wrote, “I think he is somewhat staggered, but does not give in and speaks with horror [of] what a job it would be for the next edition of ‘The Principles’ [of Geology] if he were ‘perverted’. But he is most candid and honest, and I think he will end up by being ‘perverted’,” and said , “Considering his age, his former views and position in society, I think his conduct has been heroic on the subject,” noting Lyell’s continued struggle with the subject as it pertained to Mankind’s origination from animals.

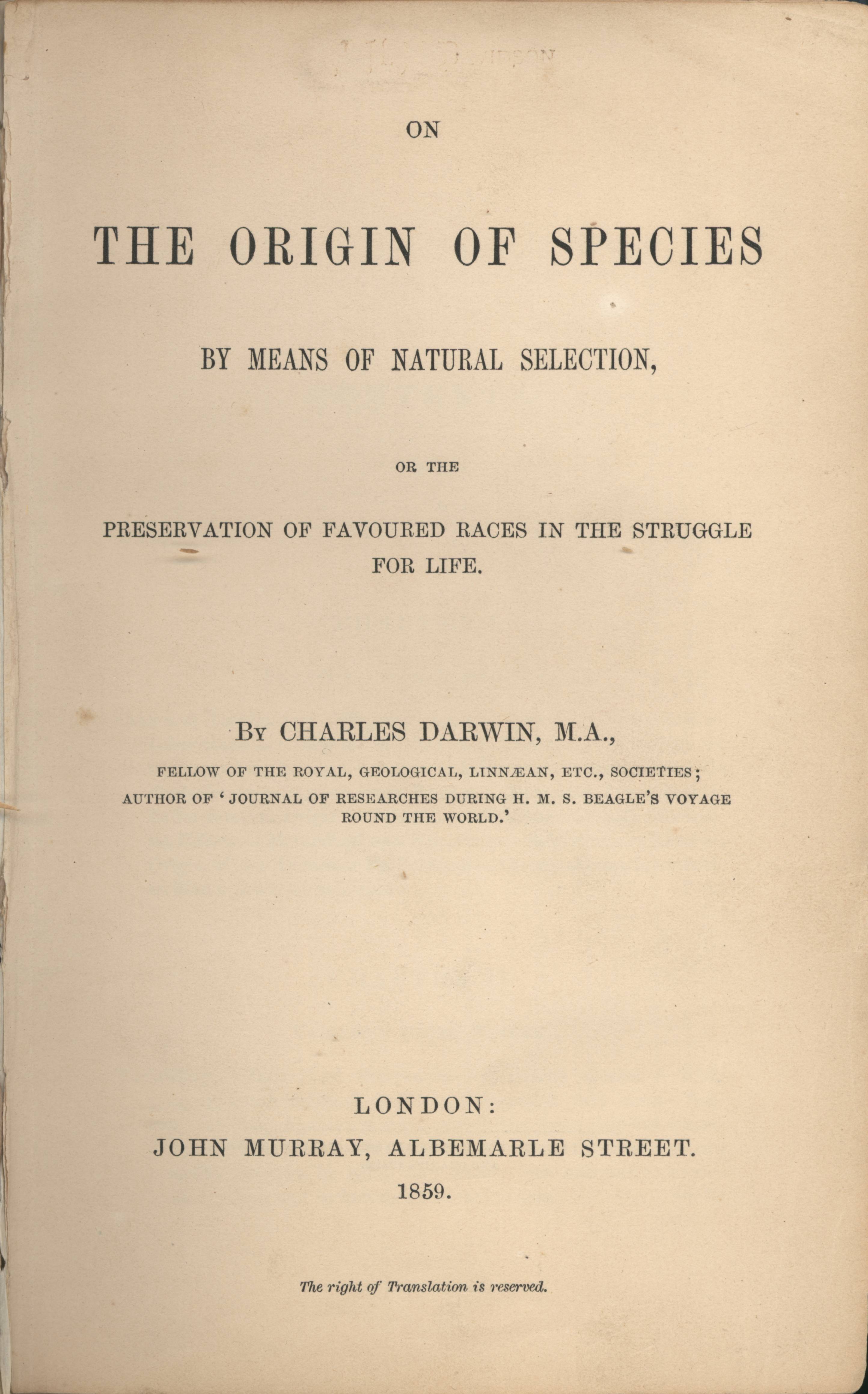

Darwin pushed forward in writing his book dealing with natural selection going into the detail he was unable to with his rush to publish his paper for the meeting. He sent chapters to Hooker for critique as they were finished, while Lyell made arrangements with a publisher to produce the book. Darwin fretted, wondering if the publisher knew the subject of the book, stating that to avoid being more “un-orthodox than the subject makes inevitable,” he abstained from mentioning the origin of man, or discussing Genesis. The publisher, John Murray, agreed to publish the book sight unseen, and to pay Darwin two-thirds of the profits. He planned to print 500 copies of the book.

This book was titled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, and Murray upped the print to 1250 copies. Darwin sent an early copy to Lyell, hoping to finally bring him around to this way of thinking, and while Lyell congratulated Darwin, he still worried “the dignity of man is at stake.” Darwin responded that, he was “sorry to say that I have no ‘consolatory view’ on the dignity of man. I am content that man will probably advance, and care not much whether we are looked at as mere savages in a remotely distant future.”

On November 2, 1859 Darwin received his first copy of On the Origin of Species, priced at 15 schillings. Darwin received many complimentary copies he mailed to his friends and those who had helped him in writing. On the copy he sent to Wallace he wrote, “God knows what the public will think.”

The book finally went on sale on November 22, 1859, and became widely circulated, with available copies selling out immediately.

In our next post, read about the immediate reactions to the publication of On the Origin of Species, and the lasting implications of it.

Further Reading:

Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991), Darwin, London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group, ISBN 0-7181-3430-3

Ball, Philip (12 December 2011). “Shipping timetables debunk Darwin plagiarism accusations”. Nature News & Comment. [Article]

Browne, E. Janet (2002), Charles Darwin: vol. 2 The Power of Place, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-7126-6837-3

Darwin, Charles (1887), Darwin, F, ed., The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter, London: John Murray (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin)

Keynes, Richard (ed.) (2000), “June – August 1836”, Charles Darwin’s zoology notes & specimen lists from H.M.S. Beagle, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press