Archives For November 30, 1999

This post, written by Mary Jo Fairchild, is one of a series that documents work studying slavery by faculty members of the CSSC.

As an archivist and historian, I gravitate towards projects that leverage research and interrogation of historic records to support and uplift social justice-oriented community work. Working with the research committee of the Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston (CSSC) gives me the opportunity to flex and engage both of these seemingly disparate devotions.

I remember the first time I began researching the College of Charleston’s ties to slavery and oppression. It was 2010 or so and I had recently completed graduate course work in American History with an emphasis on African American History at the College of Charleston. Not long after, I was appointed the Director of Archives and Research for the oldest and largest private archive in the state, the South Carolina Historical Society. My daily duties revolved around operating a bustling reading room, where students, community members, and scholars would visit and subsequently spend hours examining historic letters, diaries, newspapers, ledgers, images, maps, pamphlets and more. Very quickly I became adept at connecting a researcher with a document or record stored in one of the crowded vaults that might help answer the question that brought them to the archives.

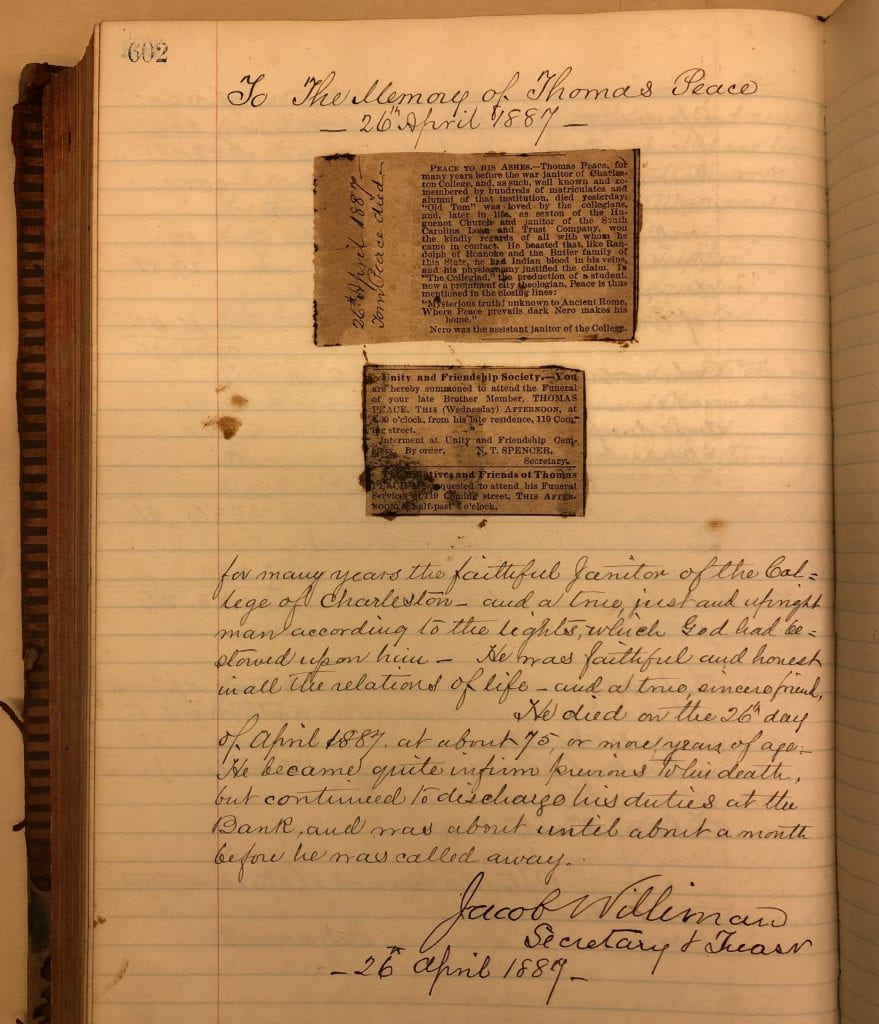

Of course, I had questions of my own and on one quiet afternoon, I fired up the old microfilm machine in the back of the library to examine capitation tax records for clues about the identity of a person named Tom Peace, whose name appears in the minutes of the Board of Trustees in several instances throughout the 19th century. At his death at “about 75 or more years” of age in 1887, the Board of Trustees published a tribute to “Old Tom, the janitor” which included the fact that Tom “boasted that he had Indian blood in his veins and his physiognomy justified the claim.” 1

Let me pause here for a moment. Capitation tax records deserve what Shereen Marisol Maraji and Gene Demby, hosts of NPR’s Code Switch podcast (consider this a HUGE plug for one of my favorite podcasts!), call a brief explanatory comma. Prior to emancipation, free persons of color in the city of Charleston were required to pay an annual “capitation tax” or head tax. Basically, free Black people (also referred to as free persons of color in the antebellum South) had to pay the city for their “free” status. Since the white ruling class could not benefit directly from the unpaid labor of free persons of color, they enacted an ordinance that taxed them to make up for the profits they would generate if enslaved, the default status of Black people in antebellum the South. The records include the names, ages, occupations, real estate holdings, and more for free Black people living in Charleston from 1811 to 1860. It is essential to acknowledge that the original purpose for keeping records for capitation taxes was rooted in the subjugation of Black lives. Nearly 300 years later, the words on the page provide the inheritors of the records with a valuable source for learning more about individuals who occupied what CSSC’s own Executive Director Bernard Powers calls an “anomalous” status, completely “dictated by the region’s commitment to slavery” in his monograph Black Charlestonians, A Social History, 1822-1855. 2

Examination of capitation tax records yielded no direct information about Tom Peace, although starting in 1845 there is a woman named Isabella Peace listed. By 1850 and 1852, the records indicate Isabella Peace was living on “St. Philip’s street near George” and at the “corner of College and George”, respectively. Both of these locations are at the heart of the college campus. I began to speculate. Was it possible that Isabella was some kin or relation to Tom Peace?

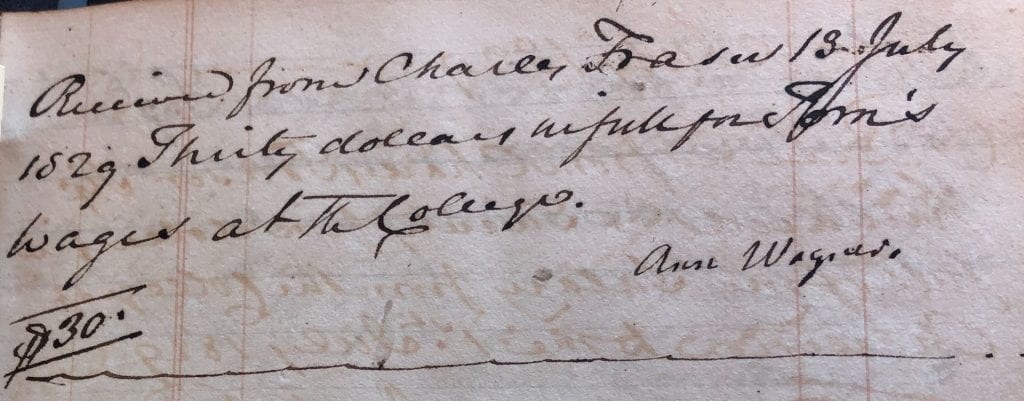

A decade after I first found Isabella Peace in the capitation tax records, I am now an archivist in Special Collections at the College of Charleston and work regularly with the College’s archives; so, not long ago I picked up the research thread I still held in the back of my mind for Tom Peace and decided to look a bit deeper. I followed financial transactions and discovered that the Treasurer of the College, Charles Fraser, was making regular monthly payments for “Tom’s wages” to a woman named Anne Wagner starting in 1829.

Could this be the Tom Peace to whom the Board of Trustees paid tribute in 1887? It is certainly possible since Tom Peace was said to be 75 years of age at his death which would make him 17 years old in 1829. Furthermore, according to the Charleston City Directory published in 1830, Anne Wagner resided at 52 St. Philip Street – again, at the heart of campus in the antebellum era. Did Ann Wagner hire Tom’s labor to her neighbors at the College of Charleston? Could Isabella Peace listed in the capitation tax records have been Tom Peace’s daughter? The silences and omissions of the historical record leave us with more questions than answers. Had the labors of men and women like Tom and Isabella Peace been properly acknowledged, compensated, and valued, we would have more than a set of financial transactions to mark their lives. It is time to mark their names and publicly acknowledge their roles and contributions.

As I said at the top, I am frequently drawn to archival research projects but I learned how to wield historical research methods for racial justice from the many scholars of race and slavery I’ve worked with in the archives. Edda Fields-Black taught me about multi-generational Black kinship networks in the Sea Islands and Toni Carrier helped me understand how to help people trace their family history when their ancestors were enslaved. Darlene Clarke Hine taught me how to look for the contributions of Black women in the historic record when the white record-makers did everything they could to erase them and Andrea Williams brought her graduate students to the archives to experience how people of African descent, enslaved and free, are present in the archives if one looks close enough and reads the silences. Gerald Horne demonstrated how the rare published travel diaries in the archives offer important perspectives absent in business ledgers and diaries kept by enslavers and Rita Reynolds took me along her journey to tell the stories of free Black women living and working in South Carolina during the antebellum era. I poured over the pages of eighteenth century ledgers searching for the name of Priscilla, a young girl kidnapped from her home in West Africa and enslaved by members of the Ball family, scratched on a page in iron gall ink to help Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Edward Ball tell her story to a national audience.

I am humbled to continue to use the skills I’ve learned over the years to participate and contribute to the mission and vision of the Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston. In solidarity with other entities and programs on campus including the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture and the Carolina Lowcountry and Atlantic World program, the CSSC provides a platform and support for scholars, faculty, students, the larger community to collaboratively mine evidence from the past, both material, written, and what exists “in between the lines”, to demonstate how the College of Charleston would not exist as we know it without the contributions of people who were historically marginalized.

Sources

College of Charleston Archives, Historical Series. Special Collections and Archives, College of Charleston Libraries.

Powers, Bernard. Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822-1855. University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Farrell, Jessica. “History, Memory, and Slavery at the College of Charleston, 1785 – 1810.” Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research Vol 7, 2008: pp. 52 – 71: https://chrestomathy.cofc.edu/documents/vol7/farrell.pdf

Rogers, Kaylee. “Overworked and Underpaid: ‘Black’ Work at the College of Charleston”. Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research, Vol 7, 2008: pp. 227-247.

“South Carolina, Charleston, Free Negro Capitation Books, 1811-1860,” https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/3405101.

Charleston City Directories: https://www.ccpl.org/city-directories

Footnotes

This post, written by Kameelah Martin, is one of a series that documents work studying slavery by faculty members of the CSSC.

My scholarly expertise sits at the crossroads of African Diaspora literature(s), primarily of the US and Caribbean, Folklore and Black Feminist Studies. I define myself as a cultural studies scholar, but I am specifically trained in the African American literary and vernacular traditions with emphasis on twenty and twenty-first century prose. My interdisciplinary reach also involves broader interests such as film, popular culture, and African spiritualities. Outside of the profession, I engage in genealogical research and acts of recalling ancestral memory. I am committed to the fields of African Diaspora Studies, Black Feminist Studies, Literature, Folklore, and Film Studies—all of my interests and expertise converge around the histories and legacies of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

It made sense, then, for me to accept a position to lead the African American Studies Program at the College of Charleston. The spiritual and historical significance of Charleston was what called me to apply for the position and I am humbled to be so deeply engaged in both academic work and the work of Spirit in the hallowed space of the port of entry for an estimated 40% of all of the enslaved Africans that entered this country. As I stand by the adage that “the personal is political,” I openly share that this work is not merely attached to my profession. My own paternal lineage finds its roots in nearby Williamsburg County, South Carolina. In 1825 an eight-year old enslaved boy “Cain” arrived in the Port of Charleston from Savannah, Georgia. I believe this to be the earliest record of Cain Cooper (b. 1817), my 5th great grandfather. And so, the work I undertake in support of CSSC is, in part, to honor my own Ancestors—the ones who rest in the Trouble Field community of Kingstree, South Carolina.

And the Ancestors have a funny way of affirming the work we do on their behalf. In 1998, as a sophomore in college I read Ntozake Shange’s novel Sassafras, Cypress, & Indigo (1982). The novel is set in Charleston, South Carolina of the 1960s. I fell in love with the youngest of the title characters, Indigo, who has “got earth blood, filled up with Geechees long gone, and the sea” (Shange 1). Never having set foot in Charleston, I vowed that if I ever bore a girl-child she would be named after my favorite novel! Well, twenty-years past before I found myself carrying that girl child—and living in Charleston, ironically. In the time between, I had studied the significance of indigo as a cash crop in the Low Country and the process of creating traditional Adire cloth in Nigeria. I had even procured a few indigo seeds from a former plantation on Ossabaw Island and successfully cultivated it (the Ancestors stay invokin’ cultural memory). I discovered that indigo was one of the sacred plants of the orisha Oshun, the Yoruba deity who has claimed my (spiritual) head. In doing spirit work with my Egun, I also discovered that indigo was the color my spirit guide wore when she walked the earth. All of this obsession with indigo was preparing me for bringing this unborn child into the world—unbeknownst to me. In the hazy, humid late afternoon of June 29, 2018 that unborn child, Indigo Amelia-Marie, made her debut in the Palmetto State—whose official state color is, of course, indigo. Her paternal lineage is “Geechee up”—to use the local parlance. Shange was right, it seems that “the slaves who were ourselves knew all about indigo & Indigo herself” (40). I stand ready for another lesson.

It has been my distinct privilege to honor the Egun with whom I share a cultural memory and legacy during the City of Charleston’s Reinternment Ceremony for the African remains discovered at Anson Street. I spoke on behalf of the Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and marched proudly as the city remembered and honored those 36 souls. Led by our beloved ‘Dr. O’ and the Gullah Society, the celebration of and spiritual rites performed for the Anson Street Burial Project is exactly the type of work I expect to be called to do while in Charleston. This is sacred work.

More to my professional endeavors, however, the subject I have privileged as a teacher-scholar explores the lore cycle of the conjure woman, or black priestess, as an archetype in literature and visual texts. In 2012, Palgrave McMillan published my first monograph Conjuring Moments in African American Literature: Women, Spirit Work, & Other Such Hoodoo which engages how African American authors have shifted, recycled, and reinvented the conjure woman figure primarily in twentieth century fiction.

I also authored Envisioning Black Feminist Voodoo Aesthetics: African Spirituality in American Cinema (Lexington 2016) which explores the treatment of the priestess figure in American cinema. My interest in film representations of black women engaged in ‘spirit work’ of the African Diaspora led me to co-edit a collection of essays, The Lemonade Reader on Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade (2016).

I’ve taught courses on the Gullah Geechee presence in African American Literature, Folklore of the African Diaspora, Voodoo & Visual Culture, and a new theory—“Conjure Feminism” that I am developing with my colleagues Kinitra D. Brooks (Michigan State University) and LaKisha M. Simmons (University of Michigan).

The conjure, hoodoo, and root medicine traditions of the US South are deeply entwined with the religious, healing, and metaphysical beliefs that enslaved Africans preserved from their ethnic origins on the continent. The conjure woman, I argue, has become a folk hero in the black imagination but to fully understand how that evolution happened I had to turn my attention to rigorous study of West African practices and the process of transculturation that took place at every settlement where enslaved Africans were held in bondage. To understand the African origins and function of practices such as the Ring Shout, making indigo dye, cooking red rice, or weaving sweetgrass baskets is to study and research the ways that enslaved Africans navigated their past with their present in the mundane, daily drudgery of their lives. This, too, is part of the important work being done through the Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and I am elated to add to the incredible work being done to foster a deeper understanding of the impact the institution of slavery has had on the everyday lives of people of African descent even in the 21st century.

This post, written by Simon Lewis, is the first of a series that documents work studying slavery by faculty members of the CSSC.

I joined the English Department at CofC in August 1996 as an Assistant Professor of World Literature, specializing in African literature. From the outset of my time here I was fascinated by the history of Charleston and the depths of its connections with West Africa — not just through the brutal experience of slavery, but also as a result of other cultural connections and legacies visible and audible in architecture, design, language and speech patterns, music, and so on. In fact, one of the earliest pieces of writing I had published after coming here was a piece for the College magazine entitled “The Africanness of Charleston.”

Just before I arrived at CofC, the College had established a new interdisciplinary program known as the CLAW Program–the program in the Carolina Lowcountry and Atlantic World. The program’s first directors set up the annual pattern of events that CLAW has put on pretty much ever since – with faculty seminars, guest lectures, panel sessions, film screenings each semester, plus, most years, an academic conference. Through this extensive programming I have gradually learned more and more about the history of the Carolina Lowcountry and Atlantic World in general and the specific history of slavery and its legacy here in Charleston. I’m proud to have been an associate director and director of the program on and off since about 2000, and grateful to have been able to contribute to the program’s impressive scholarly output, which now includes more than 20 books published either in the USC Press Carolina Lowcountry and Atlantic World series or by other academic presses, including the University Press of Florida, Louisiana State University Press, the University Press of Mississippi, and Purdue University Press. The 2017 Hines Prize-winning manuscript (awarded for a first manuscript on a Carolina Lowcountry and/or Atlantic World topic) was published by Cambridge University Press.

Front cover of Simon Lewis & David Gleeson’s edited collection, The Civil War As Global Conflict: Transnational Meanings of the American Civil War

Many of these titles have derived from major international conferences, covering topics such as the impact of the Haitian Revolution, manumission, the banning of the international slave trade, and maroonage. Many of the conferences have had significant public involvement and outreach, perhaps none more so than the 2017 “Transforming Public History” conference, which featured a keynote lecture by Smithsonian Director Lonnie Bunch in the Mother Emanuel Church. The 2018 Reconstruction conference started with the unveiling of a historical marker on Meeting Street commemorating the remarkably progressive 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention. Earlier conferences had included the unveiling of the first “Bench by the Road” by Nobel Prize-winner Toni Morrison (2008), moving ceremonies in honor of the dead of the Middle Passage (2013), and in memory of the dead of the US Civil War (2015), the latter featuring a homily by State Senator, the Reverend Clementa Pinckney, so viciously assassinated two months later.

Poster for the 2013 Jubilee Project, by SC artist Leo Twiggs.

My own role in all of these events has generally been that of something like an intellectual impresario, hosting and coordinating established scholars through series like the Wells Fargo Distinguished Public Lecture Series, but the experience has also influenced my own teaching and writing. In 2013, for instance, as an outgrowth of my coordination of the Jubilee Project SC, commemorating emancipation and educational access in Charleston in the 1860s and 1960s, I taught a graduate seminar on narratives of slavery. That course produced some stunning work by my students and gave me the material for an essay of my own on what it meant to teach such a course in Charleston, SC—Slavery Central.

Having forged partnerships and connections with institutions studying slavery around the world, the CLAW Program’s work valuably complements the work of the Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, and I am thrilled that the College is formally represented by the CSSC in the Universities Studying Slavery consortium.

If you are interested in learning more about slavery in an Atlantic World context, please spend some time on the CLAW website, and consider checking out the Addlestone Library’s compendious CLAW Libguide.