Some Other Kind of Relation That is Not Just Possible but Already at Work: Reading, Criticism, Interpretation

by EILEEN JOY

by EILEEN JOY

—Paul Strohm, Theory and the Premodern TextSomewhat prompted by Jeffrey’s two posts on what it has meant for him to serve as Chair of his departmentand some of the frustrations attendant upon advocating to sometimes unreceptive audiences the value of literary studies within the university, and also for the importance of community and shared vision when negotiating some of the university’s largest [more global] concerns relative to funding, strategic initiatives, and mission, I cannot help but be struck at the same time by the short-sightedness and perhaps even the [possibly irresponsible, or at least, disingenuous] banality of Stanley Fish’s argument, conveyed by Mary Kate in her post “Is There a Methodology in This Class?”, that the best thing we can do with a literary text is to “find out what the author meant” [i.e., hunt for and articulate the so-called “intentionality” behind literary texts, because, in the end, texts mean what their authors say they mean]. This represents, I really believe, an incredible constriction of what literary studies are capable of doing [and at a time, historically, when literary studies are imagined not to do anything of much real “use” within the university, and humanities programs have to struggle with sometimes strangulating budget limitations]. Somewhat accidentally, I also read Fish’s comments in relation to the essay by Louis Menand, “The Ph.D. Problem,” in the recent issue of Harvard Magazine [an excerpt, actually, from his forthcoming book The Marketplace of Ideas, and thank you to both Julie Orlemanski and Jennifer Brown for posting links to this on Facebook and Twitter, respectively], where Menand describes a fairly woeful state of affairs in the world of graduate studies in literature relative to the scarcity of jobs in literary studies within the university [also related, I might add, to the shrinking numbers of English majors at the Bachelor’s level], which has partly been the outcome of the profession of literary studies becoming more and more about a certain self-isolating “professional reproduction,” with no regard for whether or not there is a viable market for the growth of overly specialized, professionalized humanities disciplines… [Read the rest at In the Middle]

Some More Thoughts on Pleasure, Even More on Wonder, and Also, Some Regrets: Could Our Medieval Studies, the One We Want, Also Be a Pleasure Garden?

by EILEEN JOY

Trees write their autobiographies in circles each year,

pausing briefly each spring to weep over what they have written. I guess that’s life.

—Spencer Reece, from “Ghazals for Spring”

Literature enables us not to live a circumscribed life.

—Jeffrey Cohen, commencement address, 2009 Columban College Celebration

So I’ve been thinking a lot about our recent conversation about pleasure, and especially in relation to Karl’s questions,

When we start talking about “the world,” I’m reminded of “facts,” of “the body,” or indeed of the “we”: what do we cut away in order to arrive at any of these collective words? What gets identified as “fundamentally” world, fact, we, body? Or, to put the question another way, what do we mean when we say “the world”? When we start talking about “sharing a world,” what gets occluded? On whose terms are the feelings, objects, stances, etc. that make up the world (dis)identified? And in what sense is this concept “world” useful? Or to what ends has it been put? Or, how is a stance of “wonder” and “love” a way of manufacturing a “good conscience”?

There will be no way for me to fully answer Karl’s questions here, but I want to at least brook an attempt, especially in relation to wonder [which is, in my mind, one of the highest forms of love: it forms a zone of suspension and ontological passivity that allows almost anything to happen, and to be], and how the cultivation of wonder, or of what the political theorist Jane Bennett has called “sites of enchantment,” might be essential in the cultivation of an ethical life, and even an ethical medieval studies [and here, let’s also make room for the question I hear Jeffrey possibly asking, “why an ethical life at all, or an ethical medieval studies? why ethical? why not another term like capacious, or generous, or uncircumscribed, or open, or full, or saturated, or beautiful?”]. This will be a personal post—the most personal I think I have ever written—and it will not be academic, per se, or even medieval, although my thoughts here today tarry after and long for what I hope could be my, or our, medieval studies…[Read the rest at In the Middle]

Post-Institutional Assemblages and the Desiring-Machine of BABEL

Eileen A. Joy

Eileen A. Joy

44th International Congress on Medieval Studies, May 2009

Western Michigan University

Session 55 Getting the Medieval Studies You Want: Institutional Perspectives

Sponsor: George Washington University Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute [GW MEMSI]

Friendship is a condition of emergence, it is where my senses lead me, it is the fold of experience out of which a certain politics is born.

—Erin Manning, The Politics of Touch: Sense, Sovereignty, Movement

The BABEL Working Group began in the space of friendship, and it is my hope that it will dwell there for a long time to come. More specifically, BABEL came into being, from 2004 to 2005, partly as a result of ongoing conversations between myself and two friends in particular—Betsy McCormick and Michael Moore—over the profession of medieval studies, but also the question of whether or not humanism had a future, and if so, of what sort? Read more

Faith of a Kind: Aggressive Hermeneutics, Felicitous Weak Ontologies, and the Possibility of Interpretive Communities

by EILEEN JOY

Thanks to Karl’s flash review of James Simpson’s book Burning to Read, of which I have only read portions, I find myself continuing to be intrigued by the connections between Simpson’s book and his article, “Faith and Hermeneutics: Pragmatism versus Pragmatism” [JMEMS 33.2], especially in relation to Karl’s point [one that Holly Crocker also touched upon when she first mentioned Simpson’s book in her comment to my earlier post on Prendergast/Trigg/Dinshaw on medievalism and the supernatural] that Simpson, in his book, essentially damns William Tyndale as an intolerant fundamentalist while he also attempts to recuperate Thomas More as a more liberal reader [who nevertheless did heartily endorse execution for those who interpreted Scripture wrongly–so this is a bit of a conundrum, of course, as concerns Simpson’s argument, although in his book he freely admits this, I might add, and also offers some excuses], and all of this then raises the intriguing question [which I think Karl hints at] of whether or not Simpson brings a sort of [medieval/early modern/modern] Catholic bias to his book, which brings us right back to the question of faith and interpretation.

I bring up Simpson’s 2003 JMEMS article again because I think it relates, in deep fashion, to Simpson’s project in his book, which, as Karl has illustrated, has something to do with both:

a) issuing a kind of warning regarding fundamentalist reading/interpretive practices [which are, ultimately, based on the worst kind of fallacious circular reasoning and which have led to real, historical violences that don’t remain only in the past, say, of the western European Reformation]…[Read the rest at In the Middle]

Having the Stubbornness to Accept my Gladness in the Ruthless Furnace of the World: Cruising a Possibilistic, Potential Medieval Studies

by EILEEN JOY. . . . The poor women / at the fountain are laughing together between / the suffering they have known and the awfulness / in their future, smiling and laughing while somebody / in the village is very sick. There is laughter / every day in the terrible streets of Calcutta, / and the women laugh in the cages of Bombay. / If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction, / we lessen the importance of their deprivation. / We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure, / but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have / the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless / furnace of this world. To make injustice the only / measure of our attention is to praise the Devil. / If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down, / we should give thanks that the end had magnitude. / We must admit there will be music despite everything.

by EILEEN JOY. . . . The poor women / at the fountain are laughing together between / the suffering they have known and the awfulness / in their future, smiling and laughing while somebody / in the village is very sick. There is laughter / every day in the terrible streets of Calcutta, / and the women laugh in the cages of Bombay. / If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction, / we lessen the importance of their deprivation. / We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure, / but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have / the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless / furnace of this world. To make injustice the only / measure of our attention is to praise the Devil. / If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down, / we should give thanks that the end had magnitude. / We must admit there will be music despite everything.—Jack Gilbert, from “A Brief for the Defense”

In the story about becoming-impasse [where there is a something that isn’t shared yet, but could be], what is starved for is not sex or romantic intimacy but the emotional time of being-with, time where it is possible to value floundering around with others whose attention-paying to what’s happening is generous and makes liveness possible as a good, not a threat, and in the fear of the absence of which people choose to be with their cake.

—Lauren Berlant, “Starved”

Friendship is not a telos. Desire prevails as the moment of uncertainty whose gap in space and time we cherish, whose politics we acclaim as the point of departure, of disagreement, of sensation, of hope. . . . Friendship is human, it is of the world, it worlds. Friendship is political, it is a reminder that all thought, all sense, all touch, all language is for and toward an other. As Derrida writes, ‘there is thinking being—if, at least, thought must be thought of an other—only in friendship. . . . I think, therefore I am an other. I think, therefore I need an other (in order to think).’ Friendship is a movement of sensation, a politics of touch that that challenges me to (mis)count myself as other. Friendship is a condition of emergence, it is where my senses lead me, it is the fold of experience out of which a certain politics is born.

—Erin Manning, The Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty

You will forgive me for writing you a very long letter . . . .

I am recently returned from the annual meeting of the Group for Early Modern Cultural Studies [held in Philadelphia from Nov. 20th – 23rd] where one of the sessions—“Whither Renaissance Studies?”—was a roundtable discussion about the future of Renaissance studies, organized by Ellen MacKay and Constance Furey [both at Indiana University], and of course I was very interested to attend this…[Read the rest at In the Middle]

The Faded Silvery Imprints of the Bare Feet of Angels: Notes Toward an Historical Poethics

The Faded Silvery Imprints of the Bare Feet of Angels: Notes Toward an Historical Poethics

Eileen A. Joy

“Touching the Past”

Inaugural Symposium of the George Washington University Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute, Washington DC

7 November 2008

Eugenio Azzola, "Finestre de Bruno Schulz" (Austria, 1998)

*for Dan Remein

As I have pointed out before the design element in my paintings is the shape of love. I am wanting & hoping for a time when I can have my jaws reticulated so that I can swallow a human being whole without it having to be misshaped in order to fit into my design, fit into my love scheme.

—Stanley Spencer, 27 July 1948

I. The Hope of a Certain Astonishment

In The Writing of History, Michel de Certeau describes Michelet’s historical method, and Western historiography more generally, as a “deposition” which turns the dead into

severed souls. It honors them with a ritual of which they have been deprived. It “bemoans” them by fulfilling the duty of filial piety enjoined upon Freud through a dream in which he saw written on the wall of a railway station, “Please close the eyes.” Michelet’s “tenderness” [for the “dead of the world”] seeks one after another of the dead in order to insert every one of them into time, “this omnipotent decorator of ruins: O Time beautifying of things!” The dear departed find a haven in the text because they can neither speak nor do harm anymore. The ghosts find access through writing on the condition that they remain forever silent.[1] Read more

Silence Makes Up the Bulk of My Estate: The Burden of History—Not Then, or Later, but Now

Insofar as the losses of the past motivate us and give meaning to our current experience, we are bound to memorialize them (“We will never forget”). But we are equally bound to overcome the past, to escape its legacy (“We will never go back”). For groups constituted by historical injury, the challenge is to engage with the past without being destroyed by it. Sometimes it seems it would be better to move on—to let, as Marx wrote, the dead bury the dead. But it is the damaging aspects of the past that tend to stay with us, and the desire to forget may itself be a symptom of haunting. The dead can bury the dead all day long and still not be done.

—from Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History

Who will write the history of tears?

—from Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments

Consider this a very strange [and maybe, disorganized and not altogether intelligible] post in which I cobble together random bits and pieces from my pell-mell reading at present, and finally, from what troubles me of late, especially as regards the historical enterprise [the enterprise, in other words, of historical scholarship, historical writing, “doing History,” and so on and so forth]. In his recent post, “Messages to an Uncertain Future,” Jeffrey wrote,

Can the past speak in a voice of its own? Can meaning travel across a millennium, an epoch, or must meaning always be bestowed by an interpreter? According to linguists, a language becomes “unintelligible to the descendants of the speakers after the passage of between 500 and 1000 years.” Suppose you know that you inhabit a present that will someday, inevitably, become someone else’s distant past. How do you communicate with a future to which you will have become remote history?

As Jeffrey was likely ruminating and composing these questions, but had not yet posted them, I was driving my car from home to school and listening to Terry Gross’s radio interview [on Fresh Air] with Maher Arar, a telecommunications engineer with dual citizenship in Canada and Syria who, due to false information that Canadian authorities provided to the FBI, was arrested during a stopover at JFK airport in 2002 under suspicion [again, based on false information provided by Canada’s federal police bureau, the RCNP] of being a member of Al Qaeda, and then was deported, by CIA plane, first to Jordan and then to Syria, under our country’s draconian policy of extraordinary rendition, where he was beaten and tortured for a year in a Syrian prison, before he was finally released in 2003…[Read the rest at In the Middle]

Queer Times, Queer Bodies, and the Erotics of a Nomadic Anglo-Saxon Studies

Queer Times, Queer Bodies, and the Erotics of a Nomadic Anglo-Saxon Studies

Eileen A. Joy

2nd International Workshop of the Anglo-Saxon Studies Colloquium

Anglo-Saxon Futures: About Time 2

Kings College London

23-24 May 2008

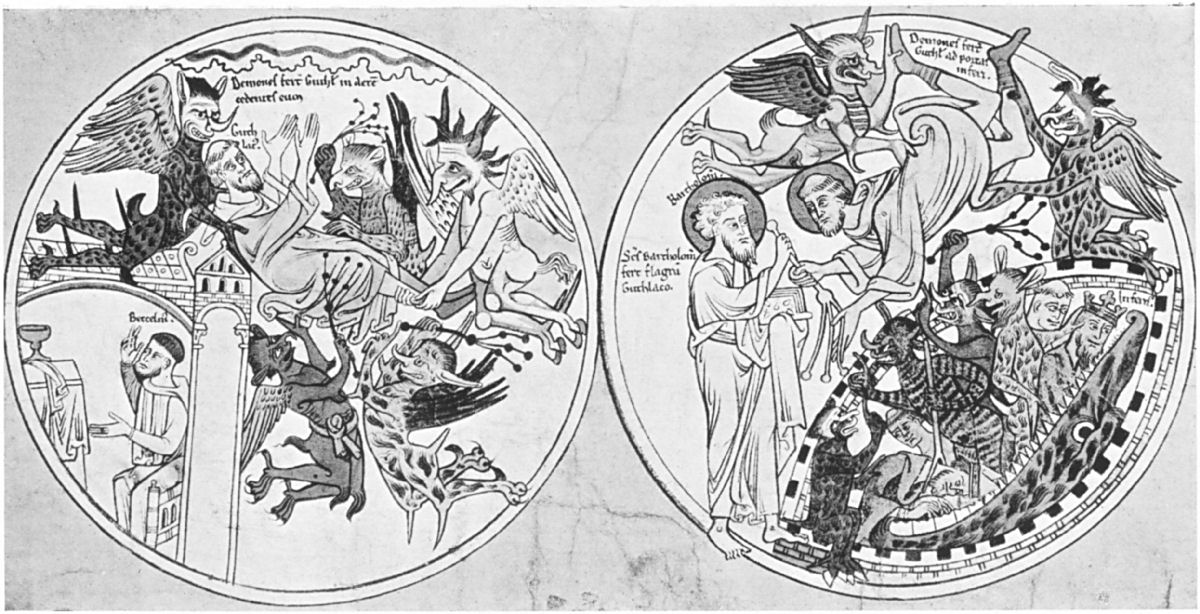

Figure 1. Guthlac born/e by his demons (The Guthlac Roll, 13th century)

Headnote: before beginning, I want to mention what Sara Ahmed refers to as the “work of inhabitance,” which involves “ways of extending bodies into space that create new folds, or new contours of what we would call livable or inhabitable space.” My thinking here, and really all of my work now, owes such a debt to what I would call the inhabitable and hospitable space, or “table,” at the weblog In The Middle, around which have gathered so many friends and passionate interlocutors. Read more

Here Now Is One Who Will Increase Our Loves: On the Virtues (and Loves) of Beautiful Singularities

I am recently back from New York City and the Medieval Club of New York’s panel, “Subjects of Friendship, Medieval and Medievalist,” and the experience—of the talks and commentary at the panel itself but also of hanging out in NYC with assorted [and lovely] persons I have known or am getting to know—has left me with more questions than I know how to answer as regards friendship, ethics, eros [broadly defined, for me, as a life-force, of which sexuality is only one powerful symptom], love, humanism, and the practices of our profession [the humanities, most broadly], all subjects that have been obsessing me of late, especially in relation to their inter- or disconnectedness with each other [and the cognitive dissonances that often result when they don’t “hook up,” and that we have to navigate every day in our traffic within the university, and elsewhere]. [Read the rest at In the Middle]

Between What Is Ours and What Is Not Ours: Claustrophilia, Attachment, Anachronism, Friendship

Between What Is Ours and What Is Not Ours: Claustrophilia, Attachment, Anachronism, Friendship

Eileen A. Joy

**a paper presented at a Medieval Club of New York panel, “The Subjects of Friendship: Medieval and Medievalist,” Graduate Center, City University of New York, 7 March 2008

Figure 1. still image from Alex Gibney's documentary Taxi to the Dark Side

What we are given is taken away,

but we manage to keep it secretly.

We lose everything, but make harvest

of the consequence it was to us.

—Jack Gilbert, from “Moreover”

Consider our place in modernity, or late or second modernity, if you will, or even postmodernity—it is a place in which, increasingly, the very notion of place, or placement, has come undone. In the words of Zygmunt Bauman in his book Liquid Modernity, “traveling light, rather than holding tightly to things . . . is now the asset of power,” and “social disintegration is as much a condition as it is the outcome of the new technique of power, using disengagement and the art of escape as its major tools” (pp. 13, 14; my emphasis). But these are strange times, too, and in some places, walls and fences and checkpoints and special “zones” are being erected and guarded with heavy weaponry, and in other places, in Bauman words, “[a]ny dense and tight network of social bonds, and particularly a territorially rooted tight network, is an obstacle to be cleared out of the way.” Read more