For the Fall 2011 Avery Messenger newsletter, I am writing a brief piece about what community archives are, some of the reasons why one would do community archiving project, and some of the benefits for the archive and archivist. In this post, I will provide a little bit more information about the role of an archivist in a community archive project. This is part one of a five-series posts.

In May 2011, I graduated with my Masters of Science in Library and Information Science from the University of Illinois’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science (www.lis.illinois.edu), where I focused on the intersection of archives and community informatics (http://www.cii.illinois.edu/). There is variation within the scholarly and academic community about what the definition of community informatics is and how it differentiates between social work, service learning, human-computer interaction (HCI), and other academic disciplines that aim to connect communities with technology. However, despite the variations, there is a central idea/concept that drives it: helping underserved and underrepresented communities bridge the Digital Divide (which in itself is a loaded term).

The definition of community can be varied; it does not just have to encompass a geographic boundary (i.e. a town, a neighborhood, a street), but also can be defined by gender, sexuality, race, religious affiliation, ethnicity, culture, occupation, organizational and corporate affiliation, etc. Thus, when a community archiving project is developed the individuals involved have to define the scope and content of what they are collecting.

The definition of community can be varied; it does not just have to encompass a geographic boundary (i.e. a town, a neighborhood, a street), but also can be defined by gender, sexuality, race, religious affiliation, ethnicity, culture, occupation, organizational and corporate affiliation, etc. Thus, when a community archiving project is developed the individuals involved have to define the scope and content of what they are collecting.

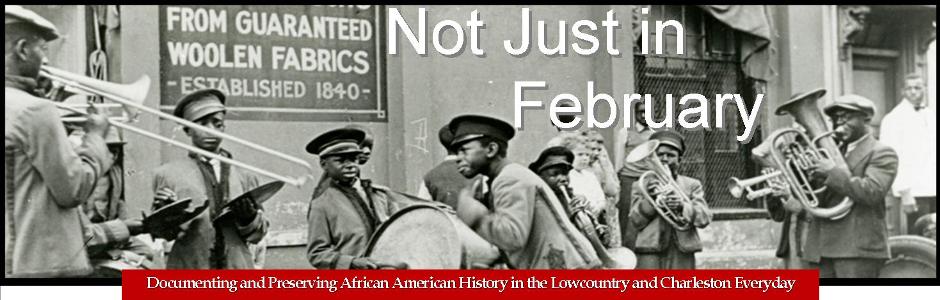

There is potential and possibilities as seen by the various projects done around the country and even the world to bring the stories and histories of these communities to the digital world. Examples include:

- Mujeres Latinas Project—http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/iwa/mujeres.html

- This project documents the lives and contributions of Latinas and their families to Iowa history.

- The Black Metropolis Research Consortium—http://www.blackmetropolisresearch.org/

- Is dedicated to making Chicago based archival holdings relating to African American history, culture, and politics more accessible to the public

- eBlackCU (eBlack Champaign-Urbana)—http://eblackcu.net/portal/

- Is an online collaborative collection that documents the history and culture of African Americans in Champaign-Urbana (IL)

- Alive in Truth: The New Orleans Disaster Oral History and Memory Project—http://www.aliveintruth.org/index.html

- Consists of the stories of displaced people after Hurricane Katrina from 2005 to 2006. The oral histories were recorded at the Austin (TX) Convention Center.

- Hurricane Digital Memory Bank—http://hurricanearchive.org/

- Is a digital collection that presents the stories and a digital record of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita survivors

However, for African-American communities, one needs to preserve and collect the physical documents before one can put the material online to be accessed by people and preserved (with the proper digital preservation policies in place). This is because much of the history of an African-American community has been dispersed, lost, and/or destroyed by those who did not know the value of what they had in their homes and/or offices. In addition, it is also important to acknowledge the fact that scholars/researchers/students who do research in communities often do not report back to those within the communities—the sources of the work. Instead, this information is kept with the scholar/researcher/student and/or institution with which the person is affiliated. Thus, the work of an archivist who wants to collaborate with and develop a community archive program is twofold.

- Provide information to communities about what the archive has about their specific community. (Note: Depending on your institution, this may not be clearly established, but think about what kinds of papers you have and if there is information/records about a community project done in the archived papers of the institution? Is there a student thesis that talks about the community? Are there maps of area? Etc.) Any type of connection (i.e. trust) that you can establish with the community is a start, especially if your institution has historically had a negative relationship with it. Doing this says this new project is going to be a give and take between the community and the archives. The more open and honest communication can be between the archival institution and the community the better. The archivist should not just push information on the organization(s)/individual(s)/institution(s); s/he is also learning from the community about its history, culture, and heritage.

- Assist and collaborate with organizations, institutions, and individuals (key and low key) to document, preserve, and collect the records/papers/materials that demonstrate the activity of the community (historical and current). Key organizations and institutions refer to the mainstream African-American organizations in the community that one automatically thinks about (ex. NAACP, the Black churches, and the Urban League). Key individuals refer to the leaders of these organizations as well as people within the community who are heavily involved in community activism and Civil Rights. Low-key organizations and institutions refer to those in the community that are small, grassroots, underground, and may not get the attention they deserve because of the populations they serve. Low-key individuals refer to those whom people do not notice or think are important, and they are usually members of low-key organizations and institutions. An example of this would be The New York City (NYC) Taxi Cab project, which consists of oral histories and records of eight NYC taxi drivers (http://nyctaxisoralhistory.com/project/items), and the Black Gay and Lesbian Archives at the Schomburg Center for Black History and Culture of the New York Public Library.

Throughout the time I am here, I will continue to post more about what community archives are, what they aim to achieve, how to start one, and the challenges and opportunities they provide.

Brief Bibliography

- Bastian, Jeannette and Ben Alexander, eds. Community Archives: The Shaping of Memory. London: Facet Publishing, 2009.

- Huvila, Isto. “Participatory archive: towards decentralised curation, radical user orientation, and broader contextualisation of records management. “Archival Science 8 (2008): 15–36.

- Ketelaar, Eric. “Sharing: Collected Memories in Communities of Records.” Archives and Manuscripts 33 (2005): 4.

- McDonald, Amy S. “Out of the Hollinger Box and Into the Streets: Activists, Archives and Under-Documented Populations” Master’s paper, UNC, 2008.

- Vos, Victor-Jan and Ketelaar, Eric. “Amsterdam Communities’ Memories: Research into how Modern Media can be applied to Archive Community Memory. “ In Constructing and Sharing Memory: Community Informatics Identity and Empowerment, edited by Larry Stillman and Graeme Johanson, 330-342. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007.

Recent Comments