In spring 2010, Julia Ellen Craft Davis and Vicki Lorraine Davis generously donated the Craft and Crum Family Papers to the Avery Research Center. Archivists and historians alike are delighted with the major highlight of the collection: a tribute book to William and Ellen Craft, enslaved people from Macon, Georgia who completed a daring escape and became internationally known celebrities.

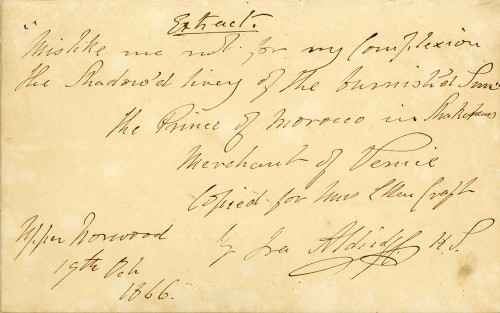

Opening the slim volume for the first time, Avery staff members gasped at the handwriting of thespian Ira Aldridge, an African American from New York who graced the London stage in the 19th century. Though celebrated in England and the European continent, Aldridge also faced enormous prejudice due to his race. Invoking the sentiments of the Prince of Morocco in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, Aldridge quoted, “Mislike me not for my complexion, / The shadow’d livery of the burnish’d sun.” With these words, Aldridge welcomed American refugees William and Ellen Craft to England and issued a shared plea for equality.

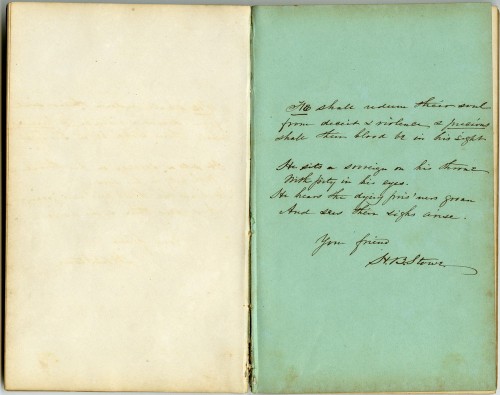

Created upon the Crafts’ entrée into English abolitionist circles, this tribute book contains passages and quotations written by well-known supporters, including the American author Harriet Beecher Stowe as well as Ira Aldridge and his wife, the Swedish countess Amanda Aldridge. A cartes-de-visite album of these figures, the Crafts, and other abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison provides a rich visual counterpart to the volume and hints at the international importance of these materials.

But just who were the Crafts and how did they emerge as public figures in the transatlantic abolitionist movement?

* * *

The frontispiece of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom portrays Ellen Craft dressed as a man, in the spirit of her escape from slavery.

In 1848, the Crafts decided to escape slavery in the American South before bringing children into the world. In an unprecedented plan, the light-skinned Ellen Craft dressed as a man and pretended to be a wealthy, white invalid seeking medical treatment in Philadelphia. Her darker-skinned husband, William, posed as her slave and generally spoke on behalf of his “master.” Traveling on public transportation and risking severe consequences if discovered, the Crafts journeyed from Macon, Georgia through Savannah, Charleston, Wilmington, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore before finally reaching freedom in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, the couple was befriended by William Lloyd Garrison, who recognized their usefulness to the abolitionist cause. The Crafts relocated to Boston and began a lecture circuit as antislavery activists.

In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it a federal crime to aid escaped slaves and permitted slave hunters to pursue escaped slaves even in free states. Their celebrity made the Crafts particularly vulnerable. The Crafts’ former owners sent two slave-catchers to retrieve them, while abolitionist members of the newly-formed Committee of Safety and Vigilance sought to protect the couple. The owners petitioned the President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, for the return of their “property.” In response, the President authorized the use of military force to return the Crafts to Southern slavery.

To flee Northern complicity in the slave system, the Crafts secured a stealth voyage to Europe, with the assistance of members of Boston’s Vigilance Committee. Only upon arrival in England did the couple finally feel free. “It was not until we stepped upon the shore at Liverpool that we were free from every slavish fear,” wrote William Craft. “We raised our thankful hearts to Heaven, and could have knelt down, like the Neapolitan exiles, and kissed the soil.”

In England, the Crafts continued to work with antislavery activists and began to raise their family. They documented their incredible journey in the poignant narrative, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. Published 1860 on the eve of the American Civil War, the Crafts’ narrative contains many accounts of slavery and freedom for blacks and discusses how they were treated in both the South and the North. Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom has been and continues to be analyzed for the issues of race, gender, and class so prevalent in the unusual façade assumed by Ellen Craft as well as challenges to her ability to be a public figure as an African American woman. Their lives and their publication hold many important comments on slavery in the South, prejudice in the North, and the international currents of the abolitionist movement.

* * *

In November 2010, the Avery Research Center acquired a first edition of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom through the generosity of the Honorable Herbert U. Fielding, the Honorable Bernard R. Fielding, The Alpha Phi Alpha Inc. fraternity, and the Friends of the Library. This rare find is a fitting complement to the exceptional Craft and Crum Family Papers acquired early last year and helps to more fully tell the incredible story of Ellen and William Craft.

On April 14, 2011, Avery will host a special unveiling of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom as well as materials from the Craft and Crum Family Papers and the H. A. DeCosta, Jr. Papers. Richard J. M. Blackett, Andrew Jackson Professor of History at Vanderbilt University, will provide more insight into this exceptional couple and their impact on the abolitionist movement.

Throughout the course of 2011, staff at the Avery Research Center will run 1000 miles to commemorate the Crafts’ courageous escape from slavery. Using “running for freedom” and the importance of literacy as central themes for this yearlong campaign, Avery and the College of Charleston will demonstrate the deep connections between literacy and agency, and the humanities and human rights movements. As the staff engages in a symbolic race for freedom, Avery advocates and the community at-large will have the opportunity to support the development of a collection acquisitions fund for the Avery Research Center.

Comments are closed.